The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

This was all the easier for me because many of our

classmates thought that Sennon, for all his affection, was a

little disturbed. But nevertheless, they all liked him, and I know

of no instance of anyone teasing him, arguing with him, or

holding his peculiarities against him, as children are wont to do.

Even the crudest of us knew that he deserved love and

consideration, for he was the kindest and most helpful person

even in his youth. Every occasion to do good to others was

welcome to him. Even if it was only the small sorrow about a

bad grade that he had received – Sennon would not rest until he

had made the afflicted person cheerful again with his loving

consolation. I myself was very attached to him, and when he

rebuked me in his gentle way, it had more effect on me than if

it had come from my own good father.

Yes, now in this spring midnight, when the wind passes

over my roof and invisible feet seem to walk along the street,

ever onward, toward an unreachable goal, everything that was

lost in the whirlpool of the young years and in the lost, terrible,

unfruitful time of this insane war sinks to the bottom of the

soul. I remembered the summer day when, to my amazement, I

saw the songbirds in the meadow on the head and shoulders of

the resting Sennon and a little weasel was sniffing at his hands.

A weasel! The shyest of all animals! And how everything

disappeared when I stepped up to him. I also remember how

Sennon helped a sick drunkard, the Pomeranian-Marie, who,

seized by severe nausea, fell to the floor with a blue face. He

picked her up, and stroked her forehead softly with his hand,

whereupon she smiled at him and continued on her way,

completely recovered. Like I was there, when blood was

spurting out of a sickle cut and it stopped when he stepped up

to it, and how the flames on the roof of the carpenter’s roof

shrank, twitched and went out, as Sennon appeared and

reached out his hand. I saw it with my own eyes. How could I

have held all this in such low regard that I forgot it? How sorry,

how unspeakably sorry I am for the years I spent so dully

beside him. I would give all my exact science to do it over.

No, I cannot approach the matter with emotional regret.

I was foolish – like all young people. When I came home

for vacations, I found that contact with the worker in Deier and

Frisch’s optical workshop was not appropriate. I preferred to go

with Herr Baron Anclever from the District Headquarters and

the dragoon lieutenant Herr Leritsch.

I cannot change it. It was like that.

But then I came to my senses. Herr Professor Schedler’s

lectures about psychic phenomena were the ones that pulled me

out of the silly life I had fallen into. I began to look into the

depths, into the twilight abyss, diving into which held a greater

incentive than chasing after little dancers, drinking sparkling

wine and conferring with morons about neck ties, pants cuts,

and race reports. I threw them out of my inner life, as one

removes useless junk from a room in which one wants to settle

into. But I also forgot about Sennon.

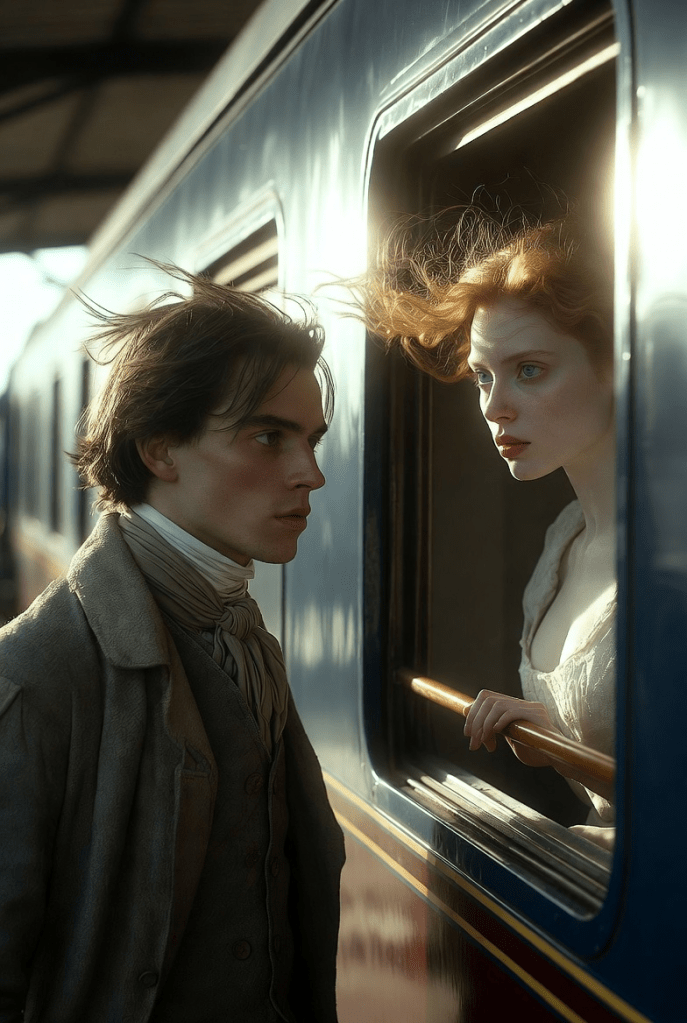

Oh, what have I lost! I put my cheek on the last leaf of

writing on which his hand rested in farewell. I call his name

and look at the black window panes in the nonsensical hope

that his dear, serious and yet so joyful face may appear behind

the glass instead of the darkness outside. Everything that I now

long for so unspeakably, was close to me, so close! I only had

to reach out my hand, just to ask. Nobody gives me an answer

now, and all my knowledge fails me. Or shall I console myself

with the vague excuse that Sennon Vorauf had a so-called “split

consciousness” and that the Ewli of Melchior Dronte could be

nothing else than an allegorical revival of the sub

consciousness, that became the second ego of Vorauf?

No, I can’t reassure myself with the manual language of

science. For I am mistaken about all of it —

When I came to Albania, occupied by us, in the course of

the war and went from Lesch to Tirana, in order to establish a

home in that cool city, with its ice-cold, shooting mountain

waters at the foot of the immense mountain wall of the Berat,

for my poor malaria convalescents, I saw Sennon Vorauf for

the last time. It was exactly that day that a searchlight crew had

just returned from Durazzo via the Shjak bazar. Among the

crew members that were searching for their quarters I

recognized Sennon.

I immediately approached him and spoke to him. His

smile passed over me like sunshine from the land of youth. He

was tanned and erect, but otherwise looked completely

unchanged. I did not notice a single wrinkle in his masculine,

even face. This smoothness seemed very strange and unusual to

me. For in the faces of all the others who had to wage war in

this horrible country, showed misery, hunger, struggles and

horrors of all kinds, and everyone looked tired and aged.

We greeted each other warmly and talked of old days.

But time was short. I had meetings and many worries about the

barracks, for the construction of which everything that was

necessary was missing. Our ships were torpedoed; nothing

could be brought in by land. Everything had to be brought in

from Lovcen, floated across Lake Scutari, and then from

Scutari brought overland in indescribable ways. Every little

thing. And boards were no small matter. I negotiated with

people whose brains were made up of regulations and fee

schedules. It was bleak; I felt like I was covered in paste and

old pulp dust. All this disturbed me. I promised Sennon I would

see him soon. He smiled and shook my hand. Oh, he knew so

surely—-!

In the afternoon a man from his department, Herr

Leopold Riemeis, came to me and had himself examined. He

had survived the Papatatschi fever but was still very weak. I

involuntarily asked him about his comrade Herr Sennon Vorauf.

His face was radiant. Yes, Herr Sennon Vorauf! He had saved

his life. A colleague, I thought and smiled. He had naturally of

course also, as I did at the time, taken a fever dream for truth.

But I was curious, gave Riemeis a cigarette and let him tell the

story.

Riemeis was a Styrian, a farmer’s son. Sluggish in

expression, but one understood him quite well. It had happened

like this: In a small town, in Kakaritschi, he, Riemeis, had been

struck down by fever. But it was already hellish. He was

burned alive, his skin was full of ulcers, and on other days he

would have liked to crawl into the campfire because of chills.

And there was no medicine left. The senior physician they had

with them shook his head. In eight days Riemeis was a skinned

skeleton, and not even quinine was left, it had long since been

eaten up.

“Go, people!” The senior physician addressed the platoon.

“If any of you has quinine with you, he should give it to

Riemeis, maybe the fever will go down, or we’ll have to bury

him in a few days.”

They would have gladly given it away, but if there is

none left, there is none left. My God, and there were already

crosses on all the roads of the cursed land, under which our

poor soldiers lay – in the foreign, poisoned earth.

“There you go, Riemeis -” said the doctor and patted him

on the shoulder. “There’s nothing that can be done.” And left.

Riemeis had a burning head that day, but he understood the

doctor quite well, “There’s just nothing that can be done.”

Sennon was sitting next to Riemeis’ bed. It was at night.

“Sennon, a water, I beg you!” moaned the sick man.

But Sennon gave no answer. He sat with his eyes wide

open and did not hear. Riemeis looked at him fearfully. And

then it happened. Something glittering fell from the forehead of

Sennon and hit the clay floor. And then Sennon moved, looked

around, smiled at his comrade, bent down and picked up a

round bottle, in which were small, white tablets. Quinine

tablets. A lot of them. From the depot in Cattaro.

Our peasants are strange. They didn’t say anything to the

doctor, but they put their heads together and whispered.

“My grandfather told -“.

They did not question Sennon about it. They were shy.

But they surrounded him with love and reverence, took

everything from him, did all the work for him, and listened to

his every word. And they understood well that it was precisely

on his heart that all the suffering of the poor lay, who were

driven into this killing, without even being considered worthy

of questioning. This is not an accusation. Our country was in

danger. Even those in power over there did not ask anyone.

How else could they have waged war? How could they take

revenge on us because we were more efficient and industrious?

But why do I speak of these things! It will take a long time

until mankind will be able to judge justly again. So Sennon

Vorauf.

He bore the woe of the earth, all the misery of countless

people, and his heart wept day and night. Even though he

smiled. They understood well, his comrades, and it would not

have been advisable for anyone to approach Vorauf. Not even a

general. The people had gone wild through their terrible

handiwork. But there was no opportunity. Never has there been

a more well-behaved, more dutiful man than Vorauf, but they

all thought that shooting at people – no, no one could have

made him do that. Riemeis said.

Oh, I had to go and mark out the ground for the barracks.

I asked Riemeis to give Sennon my best regards. I would come

tomorrow. Yes, tomorrow! Already that evening I had to leave

for Elbassan.

Then came the letter from Riemeis to me and a copy of

the desertion notice.

But fourteen days passed before I could leave for Tirana.

A full fourteen days. I hoped that Vorauf would have been

found after all.

First I visited the commander of Vorauf’s department,

who had filed the complaint, Herr Lieutenant Wenceslas

Switschko. I found a fat, limited, complacent man with

commissarial views, for whom the case was clear. Vorauf, a so-

called “intelligent idiot”, had deserted, and the Tekkeh he had

disappeared into certainly had a second exit. One already

knows the hoax. But, woe betide if he were brought in! Well, I

gave up and went to the people. Riemeis received me with tears

in his eyes. Corporal Maierl, too, a good-natured giant, a

blacksmith by trade, had to swallow a few times before he

could speak. They recounted essentially what was written in

Riemei’s letter to me. We went to the Tekkeh of the Halveti

dervishes. Slate-blue doves cooed in the ancient cypresses. A

rustling stream of narrow water rushed past the wooden house

and the snow covered crests of the Berat Mountains shone

snow-white high above the pink blossoming almond trees and

soft green cork oaks. In the open vestibule of the Tekkeh stood

large coffins with gabled roofs, covered with emerald green

cloths. On each of them lay the turban of the person who had

been laid to rest.