OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

Chapter 15

Max Heiland had actually felt a troubling premonition all day, and it was foolish of him to stubbornly suppress and dismiss it.

This premonition warned him against visiting his lodgings on Kohlmarkt today, and he would have been wise to heed it.

For when he heard Ottane’s light step on the stairs and then her signal at the door, and when he—now with some difficulty—assumed the face of the delighted lover and opened the door, there stood Therese Dommeyer before him.

Damn it all, how could his sharp hearing have deceived him so—now the reckoning was at hand.

“Quite cozy you’ve got it here,” said Therese, stepping in and closing the door behind her.

“Who: we?” asked the master, rather lacking in wit.

Therese went further; she removed the key and tucked it into her fold-up purse. Then she said, “Well, you and your lover.”

Max Heiland deemed it appropriate to react gruffly: “What kind of foolish talk is this?”

“So is this perhaps your new studio? I don’t know much about it, but it seems the light isn’t great. I think I’ll have to shed some light on this for you.”

“So what do you want here?”

“I’d like to meet your lady.”

There was nothing to do but give in a little. “I beg you, Therese, surely you don’t want to cause a scandal!”

“I’m just curious about who comes to see you.”

“Very well… but you must give me your word of honor to cause no scandal.” He choked out the name as an honorable man yielding only to necessity. “It’s Frau Oberstin Arroquia!”

He breathed a sigh of relief. “You understand… a Spaniard like that… what can one do? It’s practically a business matter. Frau Arroquia has connections to court circles, the best connections, and if she ends our friendship and turns the entire nobility against me—well, I’d look pretty foolish. One can’t afford to offend a woman like that.”

Therese hadn’t been listening to the master and was sniffing around the room. “Yes, one mustn’t offend a Spaniard like that,” she said, continuing to sniff. She picked up a silk scarf from an armchair and examined it: “This shawl looks familiar, but I think I’ve seen it with someone else.”

Yes, there hung Ottane’s shawl, and on the dresser stood a prominent, unmistakable picture—Ottane’s daguerreotype, taken by Schuh, with a small vase of roses before it, like a household altar of love. Therese stood reverently before the image and said, “But the Frau Oberstin has changed remarkably lately.”

Good heavens, Max Heiland realized everything was lost—Ottane’s picture was there, and on top of that, he had placed roses before it out of exaggerated chivalry.

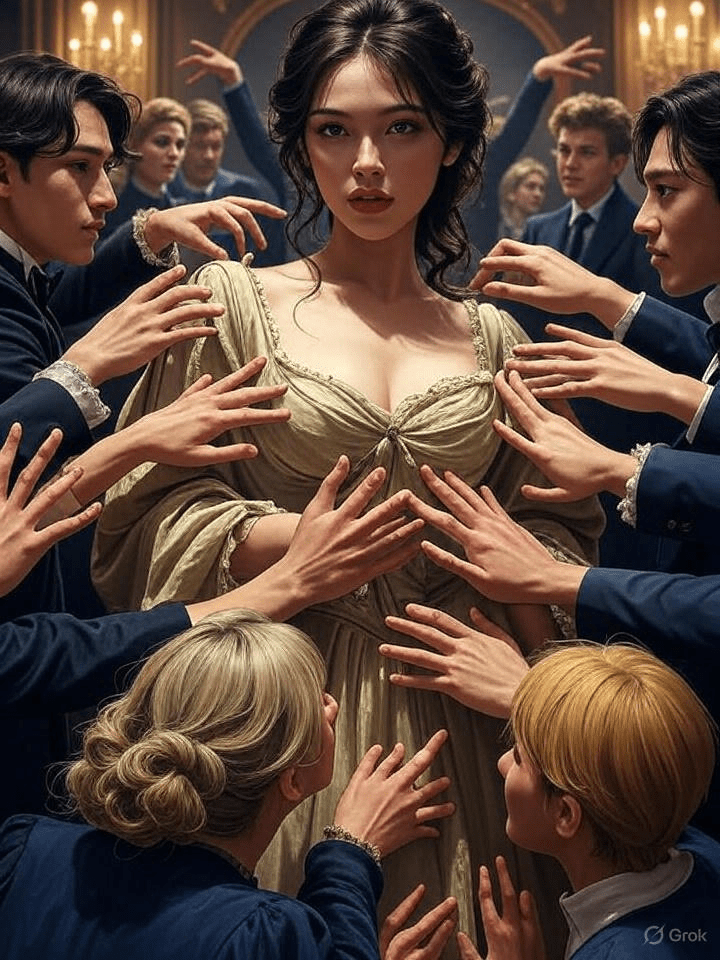

“So it’s Ottane,” Therese turned around, “this little game with Ottane, with whom you’ve been cheating on me. Is this also because of court circles and business considerations?”

Now further denial would be pointless, mere waste of time, and there was no time to lose. Ottane’s moment was at hand; she could arrive at the door any second, and what might follow was unthinkable. A confrontation must be avoided at all costs. Max Heiland gave himself a shake and stood up straight: “I’ll tell you the truth. It really is Ottane. And what do you intend to do now?”

“I’ll wait here until she comes,” said Therese, settling broadly into a chair with rustling skirts.

“You won’t do that, my dear.”

“Don’t call me ‘my dear’!” Therese flared up angrily. “You know I can’t stand that.”

“You won’t do that because you don’t need to. It’s entirely unnecessary for you to make a scene. You’ve discovered this… well, this affair at a time when it’s nearly resolved for me. You’ve only hastened its natural end. In a few days, I would have broken with Ottane. I’ve had enough of her.”

Therese raised heavy eyelids with a look that suggested little trust. “Is that true?”

Heiland nodded affirmatively. He had spoken the truth—at least a kind of truth; he had indeed grown somewhat weary of Ottane. Her passion no longer swept him away; he remained more out of politeness and favor than from an inner urge as a tender lover. He had other life goals, other women, and his work; in truth, he was already bored, and Therese’s intrusion into the fading love idyll merely provided the external push to end it. It excused the violent act, to which he hadn’t yet been able to resolve himself out of pity and consideration.

“If I’m to believe you,” said Therese, “then write a farewell letter to her right now.”

“I’m ready to do that,” Heiland conceded, with the seriousness befitting such a moral turn. He sat at the small desk, took paper and pen, and began to write.

“And to make it easier for you,” Therese continued, twirling Ottane’s shawl in the air until it formed a rope, “you’ll come away with me now.”

Heiland looked up in surprise.

“Yes, I’ve been granted leave; I must make a guest performance tour in Germany, and you’re coming with me.”

All respect, one had to give Therese credit—when she did something, she did it thoroughly. “Very well,” said the master after a brief reflection, “I’ll go with you. It might do me good to take a break for a while. I don’t know what’s wrong with my eyes; sometimes it’s like a veil over them, and then I can hardly see nearby things. It will benefit my eyes to not paint for a few weeks.”

He wrote a few more lines and then asked over his shoulder, “And your old man?”

“My old man?” Therese wrinkled her nose. “The Reichenbach? Yes, he’ll have to manage without me.”

Now Heiland even managed his captivating smile again: “But you must tell me how you found out… that we were here…?”

“You’d like to know, you sly one!?” Therese laughed, half-reconciled. “I just have very good connections with the police. The police know everything, and it was an honor for the Hofrat to oblige me.”

Heiland hurried to finish his letter, for now there was no minute to spare.

“Show me!” Therese commanded as he sprinkled sand over the ink. She read it, nodded, was satisfied; and then they didn’t linger any longer. Heiland felt the ground burning beneath his feet—my God, only not another encounter at the last moment on the stairs, in the stairwell, or on the street, an open confession. Heiland wasn’t fond of awkward confrontations; his quota was fully met by Therese. He breathed a real sigh of relief only when they turned the next street corner.

Ottane arrived quite flushed; an urgent operation that Semmelweis wouldn’t perform without her had caused the nearly half-hour delay. As she entered the house, the curtain at the caretaker’s window moved, and then the caretaker emerged, holding a letter.

“Herr Heiland just left with a lady… and I’m to give you this letter.” Rarely had Frau Rosine Knall carried out an errand with such satisfaction. The foolish Doctor Semmelweis had dismissed her—that was an outrage—and her disposition toward him hadn’t improved with the neighborhood joke that she’d been fired on the spot. She knew this young lady was, so to speak had taken her place—this person who took bread from poor women and, of course, indulged Semmelweis in his madness. She included Ottane with fervor in her resentment; it had been a delight to provide information to the police spy when he came to inquire, and now she had lurked behind the curtain of her door window like a hunter on the lookout.

The arrow had been loosed—this letter, she knew, was a poisoned dart. Ottane realized it the moment she received the letter.

“Thank you!” said Ottane and walked away. Only don’t let this woman notice anything, only don’t give those greedy, hateful eyes a spectacle. She walked a few houses down and stepped into a wide gateway.

She knew what the letter contained; she had sensed it coming. Max Heiland’s arts hadn’t been enough to deceive the feeling that something dreadful approached; the hours of passion had been followed by bitterness, a gaze into emptiness, a rise of fear.

Now Ottane held the letter in hands that trembled as they broke the seal.

She read: “My conscience can no longer allow…”

She read: “I cannot bring myself to involve a girl from a first family, so pure and blameless…”

She read: “Under this conflict, my art and the noble purpose of my existence suffer…”

She read: “Though my own heart bleeds from a thousand wounds…”

She read: “And so I depart alone…”

Ottane leaned against the wall; her legs stood in a mire into which they sank. The view of the street through the gateway swung in pendulum motions left and right. Then she heard voices from above; footsteps clattered down the wooden stairs, a child crowed with delight.

No, only don’t let anyone notice, for God’s sake, don’t let anyone notice.

She pushed off from the wall, staggered a little, but then walked out into the life of the street.

“Are you packing?” said Freiherr von Reichenbach, surprised, as he entered Therese Dommeyer’s room.

She stood with her maid amid piles of clothing and feminine accessories, wrestling with a stubborn suitcase.

“Are you traveling?” the Freiherr asked again, faced with these unmistakable preparations.

“Yes, I’m traveling,” laughed Therese. “I’m going to Germany—Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin, and so on, a big guest performance tour…”

“You must be very excited about it?” the Freiherr remarked, distressed.

Therese, with the maid’s help, had subdued the unruly suitcase. She jumped onto the lid and held it down with the sweet weight of her body while the maid quickly fastened the straps.

“I’m overjoyed. A chance to get out of the Viennese sausage kettle, see new faces, and earn a bit of money!”

Therese was evidently not the least bit saddened by the farewell; she sat soulfully delighted on the lid, drumming the sides of the suitcase with the heels of her cute shoes.

A shadow of melancholy darkened Reichenbach’s features: “I came to invite you to a session, but…”

“Yes, with the sessions, that’s over now,” Therese waved off. “Now you’ll have to sit without me. And I’m not sensitive anymore.” She leaped off the restrained suitcase and dove into a pile of clothes. “Jesus, Rosa, where’s the blue hat? Haven’t you seen the blue hat? It was still in the bedroom a moment ago.”

The maid slipped out; they were alone for a short while, perhaps only minutes, as Rosa would return soon. Reichenbach hadn’t come solely for the session—the matters needed clarification, and with no time for slow deliberation, a bold move was needed to force a decision.

“And I had thought—” said the Freiherr, looking at Therese with heartfelt emotion.

“Well, man proposes, and God and the theater agent dispose.”

“You can’t be in doubt,” Reichenbach pressed on resolutely, “about what I mean, can you? You must have noticed it yourself long ago. I came here today with a specific intention. I… I had hoped to take your ‘yes’ home with me today, that you… well, that you would become mine.”

Therese was neither surprised nor overwhelmed by the great honor; she had no time to feign surprise or emotion, nor to artfully soften her rejection. “Look, dear Baron,” she said, digging a violet petticoat from a stack of clothes and tossing it onto a nearby pile, “look, dear friend, you must get that idea out of your head. That’s just not possible. How do you even imagine it? There’s no question of it. I don’t suit you, and you don’t suit me. We get along well enough, but as your wife—no, that won’t do. So, what about the hat, Rosa?”