Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

“How do you like it?” she asked him.

“Why should the little man be there?” he retorted.

She said, “He belongs there!–I didn’t like the golden Cupid–That

is for all the other people–I want to have Galeotto, my root manikin.”

“Why do you call it that?” he asked.

“Galeotto!” she replied. “Wasn’t it him that brought us

together?–Now I want him to hang there, to watch over us through the

night.”

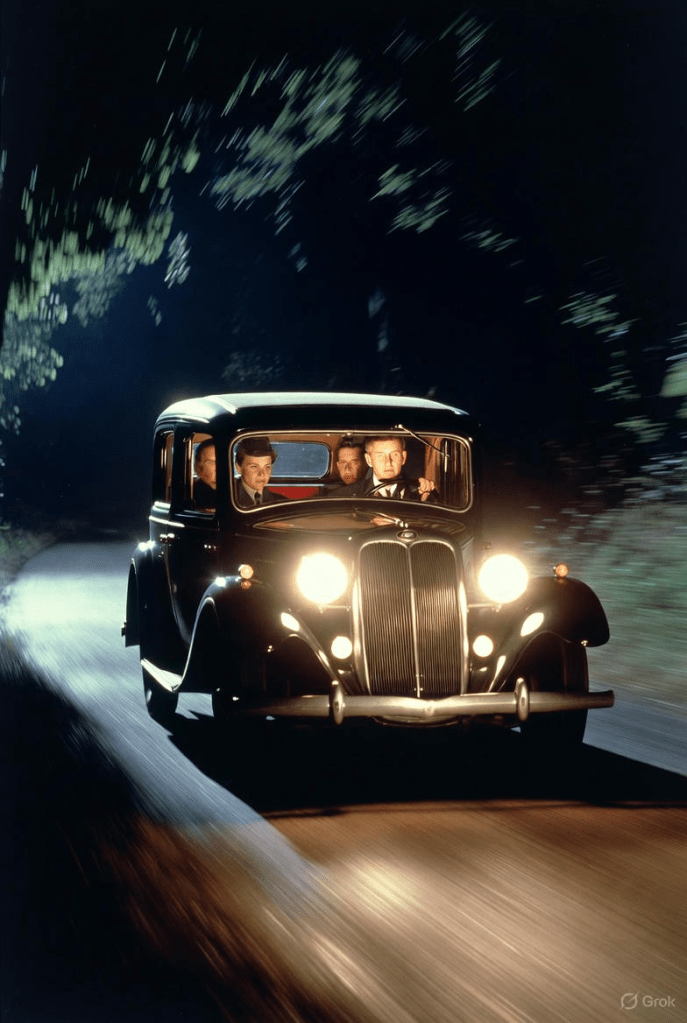

Sometimes they went out riding in the evenings or also during

the night if the moon was shining. They rode through the Sieben

Gerberge mountain range or to Rolandseck and into the wilderness

beyond.

Once they found a she-donkey at the foot of Dragon’s Rock in

the Sieben Geberge mountain range. People there used the animal for

riding up to the castle at the top. He bought her. She was a young

animal, well cared for and glistened like fresh snow. Her name was

Bianca. They took her with them, behind the horses on a long rope,

but the animal just stood there, planting her forelegs like a stubborn

mule, allowing herself to be choked and dragged along. Finally they

found a way to persuade her. In Kőnigswinter he bought a large bag

full of sugar, took the rope off Bianca and let her run free. He threw

her one piece of sugar after the other from out of the saddle. Soon the

she-donkey ran after them, keeping itself tight to his stirrup, snuffling

at his boots.

Old Froitsheim took the pipe out of his mouth as they came up,

spit thoughtfully and grinned agreeably.

“An ass,” he chewed. “A young ass! It’s been almost thirty years

since we’ve had one here in the stable. You know, young Master, how

I used to let you ride old gray Jonathan?” He got a bunch of carrots

and gave them to the animal, stroking her shaggy fur.

“What’s her name, young Master?” he asked.

Frank Braun told him her name.

“Come Bianca,” spoke the old man. “You will have it good here

with me. We will be friends.”

Then he turned again to Frank Braun.

“Young Master,” he continued. “I have three great-grandchildren

in the village, two little girls and a boy. They are the cobbler’s

children, on the road to Godesberg. They often come to visit me on

Sunday afternoons. May I let them ride the ass?–Just here in the

yard?”

He nodded, but before he could answer the Fräulein cried out:

“Why don’t you ask me, old man? It is my animal. He gave it to

me!–Now I want to tell you–you are permitted to ride her–even in the

gardens, when we are not home.”

Frank Braun’s glance thanked her–but not the old coachman. He

looked at her, half mistrusting and half surprised, grumbled something

incomprehensible and enticed the donkey into the stable with the

juicy carrots.

He called the stable boy, presented him to Bianca, then the

horses, one after the other–led her around behind the farmyard,

showed her the cow barn with the heavy Hollander cows and the

young calf of black and white Liese. He showed her the hounds, both

sharp pointers, the old guard dog and the cheeky fox terrier that was

sleeping in the stable. Brought her to the pigs, where the enormous

Yorkshire sow suckled her piglets, to the goats and the chicken coop.

Bianca ate carrots and followed him. It appeared that she liked it at

the Brinken’s.

Often in the afternoons the Fräulein’s clear voice rang out from

the garden.

“Bianca!” she cried. “Bianca!”

Then the old coachman opened her stall; swung the door open

wide and the little donkey came into the garden at an easy trot. She

would stop a few times, eat the green juicy leaves, indulge in the high

clover or wander around some more until the enticing call rang out

again, “Bianca!” Then she would search for her mistress.

They lay on the lawn under the ash trees. No table–only a large

platter lay on the grass covered with a white Damascus cloth. There

were many fruits, assorted tid-bits, dainties and sweets among the

roses. The wine stood to the side.

Bianca snuffled, scorned the caviar and no less the oysters,

turned away from the pies. But she took some cake and a piece of ice

out of the cooler, ate a couple of roses in between–

“Undress me!” said Alraune.

Then he loosened the eyes and hooks and opened the snaps.

When she was naked he lifted her onto the donkey. She sat astride on

the white animal’s back and held on lightly to the shaggy mane.

Slowly, step by step, she rode over the meadow. He walked by her

side, lying his right hand on the animal’s head. Bianca was clever,

proud of the slender boy whom she carried, didn’t stop once, but went

lightly with velvet hoofs.

There, where the dahlia bed ended, a narrow path led past the

little brook that fed the marble pool. She didn’t go over the wooden

bridge. Carefully, one foot after the other, Bianca waded through the

clear water. She looked curiously to the side when a green frog

jumped from the bank into the stream. He led the animal over to a

raspberry patch, picked the red berries and divided them with

Alraune, continued through the thick laurel bushes.

There, surrounded by thick elms, lay a large field of carnations.

His grandfather had laid it out for his good friend, Gottfried Kinkel,

who loved these flowers. Every week he had sent the poet a large

bouquet for as long as he lived. There were little feathery carnations,

tens of thousands of them, as far as the eye could see. All the flowers

glowed silver-white and their leaves glowed silvery green. They

gleamed far, far into the evening sun, a silver ground.

Bianca carried the pale girl diagonally across the field and then

back around. The white donkey stepped deeply through the silver

ocean; the wind made light waves that kissed her hoofs.

He stood on the border and watched her, drank in the sweet

colors until he was sated. Then she rode up to him.

“Isn’t it beautiful, my love?” she asked.

And he said sincerely, “–It is very beautiful–ride some more.”

She answered, “I am happy.”

Lightly she laid her hand behind the clever animal’s ears and it

stepped out, slowly, slowly, through shining silver–

“Why are you laughing?” she asked.

They sat on the terrace at the breakfast table and he was reading

his mail. There was a letter from Herr Manasse, who wrote him about

the Burberger mining shares.

“You have read in the newspapers about the gold strike in the

Hocheifel,” said the attorney. For the greatest part the gold has been

found on territory owned by the Burberger Association. It appears

very doubtful to me that these small veins of ore will be worth the

very considerable cost of refining it. Nevertheless, your shares that

were completely worthless four weeks ago, now, with the help of the

Association’s skillful press release have rapidly climbed in value and

have been at par for a week already.

Today, I heard through bank director Baller that they are

prepared to quote them at two hundred fourteen. Therefore I have

given your stocks over to my friend and asked him to sell them

immediately. That will happen tomorrow, perhaps they will obtain an

even higher rate of exchange.”

He handed the letter over to Alraune.

“Uncle Jakob himself, would have never dreamed of that,” he

laughed. “Otherwise he would have certainly left my mother and me

some different shares!”

She took the letter, carefully read it through to the end. Then she

let it sink, stared straight ahead into space. Her face was wax pale.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“Yes he did–He did know it,” she said slowly. “He knew exactly

what he was doing!”

Then she turned to him.

“If you want to make money–don’t sell the shares,” she

continued and her voice rang with conviction.

“They will find still more gold–Your shares will climb still

higher–much higher.”

“It’s too late,” he said lightly. “By this hour the shares have

probably already been sold! Besides, are you all that certain?”

“Certain?” she repeated. “Certain? Who could be more certain

that I?”

She let her head sink down onto the table, sobbed out loud, “So it

begins–so–”

He stood up, laid his arm around her shoulder.

“Nonsense,” he said. “Beat that depression out of your brain!–

Come Alraune, we will go swimming. The fresh water will wash the

foolish cobwebs away. Chat with your mermaid sisters–they will

confirm that Melusine can bring no more harm once she has kissed

her lover.”

She pushed him away, sprang up, stood facing him, and looked

him straight in the eyes.

“I love you,” she cried. “Yes, I do–But it is not true–the magic

does not go away! I am no Melusine, am not the fresh water’s child! I

come out of the earth–and the night created me.”

Shrill tones rang from her lips–and he didn’t know if it was a sob

or a laugh–

He grabbed her in his strong arms, paid no attention to her

struggling and hitting. He held her like a wild child, carried her down

the steps and into the garden, carried her screaming over to the pool,

threw her in, as far as he could with all her clothes on.

She got up and stood for a moment in amazement, dazed and

confused. Then he let the cascades play and a splashing rain

surrounded her. She laughed loudly at that.

“Come,” she cried. “Come in too!”

She undressed and in high spirits threw her wet clothes at his

head.

“Aren’t you ready yet?” she urged. “Hurry up!”

When he was standing beside her she saw that he was bleeding.

The drops fell from his cheek, from his neck and left ear.

“I bit you,” she whispered.

He nodded. Then she raised herself up high, encircled his neck,

and drank the red blood with ardent lips.

“Now it is better,” she said.