Homo Sapiens: In the Maelstrom by Stanislaw Przybyszewski and translated by Joe E Bandel

XII.

“Now you must go to Geißler and arrange everything with him, then we can leave the day after tomorrow.”

Falk stood thoughtfully for a while. “Yes, yes… we will leave soon.” He smiled distractedly.

“You love him very much, didn’t you?” he asked suddenly. “Who?”

“Well, Geißler of course. If something should happen to me, you could marry him, couldn’t you?”

He looked at her smiling.

“Die first, then we will see,” Isa joked. “Well, then goodbye.”

“But don’t come back so late again. I have such fear for you now. Think of me: I will go mad with unrest if you stay out long again today.”

“No, no, I will come soon.” He stepped onto the street.

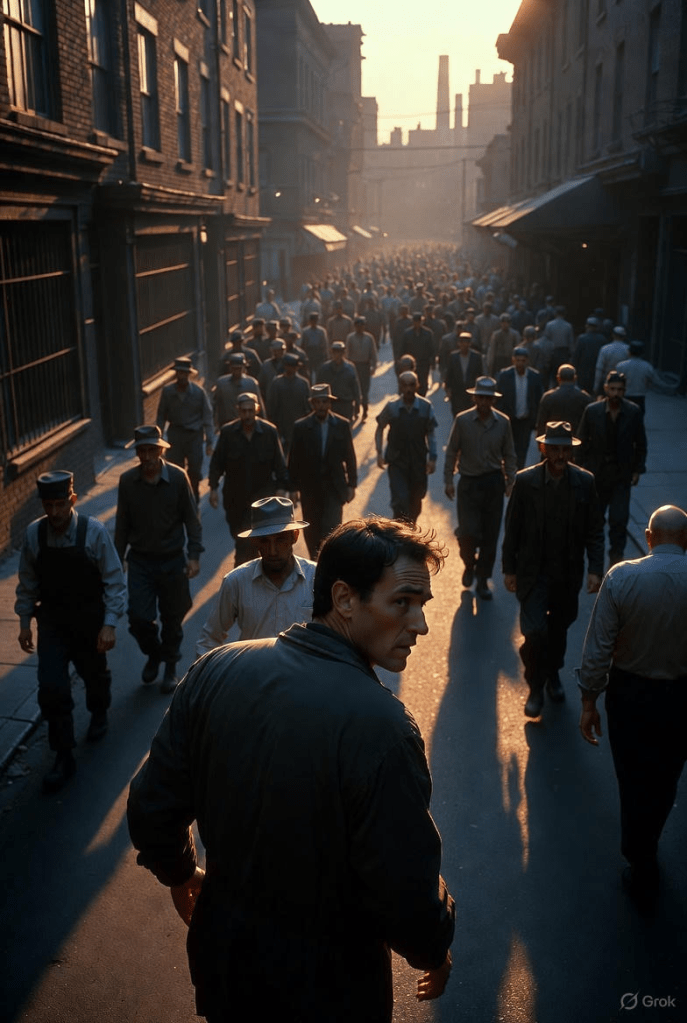

It was just quitting time, the workers streamed in large crowds from the factories.

Anxiously he turned into a side alley. It was generally strange what everything now became fear for him; his heart was in constant fever activity.

If he heard a noise at the door, he started and could not calm down for a long time; he heard little Janek cry and started in highest fear: he could not remember for a long time that he had a son, no, now he even had two: little Janek and little Erik, two sweet, wonderful children…

Oh, this splendid father idyll! If only it were not so infinitely comical.

He walked thoughtfully along the empty street.

The events of the last days whirred through his head and blurred into a feeling of an unspeakable sadness. It seemed to him as if he must suffocate: he breathed deep and heavy.

What would it help if he fled? Not travel, only flee, flee, so that his lies would not be discovered? He could no longer live with all the disgusting lies, now he could no longer look Isa calmly in the eyes: her trust, her faith tormented him, humiliated him, he felt disgust for himself, tormenting shame, that he would most like to have spat at himself.

Strange woman, this Isa. Her faith has hypnotized her. She walks like a sleepwalker. She sees nothing, she hardly suspects that he suffers. The awakening will be horrible. It cannot go on: her faith will now be broken sooner or later anyway.

“So I am a double criminal. I broke the marriage and its condition, faith. Actually I am only a criminal against myself, for I cut the roots of my existence. I cannot live without Isa after all. However I think and consider: it does not go. And because I am I, because I am thus God, for God is everyone who makes everything around him his thing—and everything around me is my thing—, so I have sinned against God, thus committed a sacrilege.”

He spoke it half-aloud with deep reflection to himself, suddenly noticed it and stopped.

That could not be his seriousness, he knew no crime after all. No, whatever he might think about his heroic deeds, the concept of crime could not be constructed. Crime postulates a state of mind that is precisely no coziness… He, he, he, coziness!—I actually wanted to say heartlessness. Well, the devil knows, I am anything rather than heartless. I have more pity in me than our whole time together. So I am no criminal.

He lost himself in the subtlest investigations.

“But perhaps a state of feeling is now forming that did not exist before, and for which something counts as crime that was by no means crime before. A feeling of offense against civilizational developments, e.g. against monogamy.”

But his brain was so exhausted that he could not pursue the thought further: it was also indifferent; the brain with all its lawyer tricks was quite powerless against the feeling. Why brood further then?

He suddenly got the sure, immediate certainty that now everything would be in vain, whatever he did, that the terrible would now surely, unavoidably, with iron necessity break over him.

He shuddered and his knees became weak. He looked around: no bench nearby.

With difficulty and despair he dragged himself further.

His brain now became quite distracted, he could no longer concentrate it. Instead he saw with uncanny clarity the slightest details. So he saw that a letter hung crooked on a sign, that a bar was bent outward on a grating, that a passer-by had the characteristic gait of a person whose boots fit badly.

His brain exhausted itself in these trifles. Suddenly he cried out softly.

The thought that he had heard working all day in the lowest depth, and that he had tried so hard to stifle, broke through.

He had to follow Grodzki!

He had so often considered suicide theoretically, but this time it was like a huge compulsion suggestion: he felt that he could not resist it. It did not come from outside, no, it came from the unknown: a domineering will stifling every contradiction.

He trembled, staggered, stopped and supported himself against a house.

He had to do it! Just as Grodzki had done it. Train the brain will for it, force it to obey the instinct will.

Suddenly he felt a peculiar numb calm. He forced himself to think, but he could not, he went further and further thoughtlessly, sunk in this numb, inner death silence.

He stumbled and almost fell. That shook him up. No! it was not hard, why should he torment himself longer.

He thought what would not be torment, but he could find nothing. Then he thought what would not be lie, but there was nothing that it was not, at most a fact, but what is a fact, said Pilate and washed his hands. No! Pilate said: what is truth? and only then did he wash his hands.

He began to babble.

But when he came to the house where Geißler had to live, he became very restless.

He had completely forgotten the house. But here he had to live. He read all the signs, among them especially attentively: Walter Geißler, lawyer and notary, but he could not orient himself.

He went into the hallway, stepped out onto the street again, read the signs again, came to his senses and became half unconscious with fear.

Should he go mad? That was after all a momentary confusion of senses. Oh God, oh God, only that not!

He collected himself with difficulty, a morbid shyness to show no one what was going on in him began to dominate him.

He directed the greatest attention to his face, made the strangest grimaces to find out the expression of indifferent everydayness, finally felt satisfied and went up.

“One moment!”

Geißler wrote as if his life depended on it. Finally he jumped up.

“I namely have insanely much to do. I now want to hang my law practice finally on the nail and devote myself entirely to literature. That is after all a charming occupation, and I work now to unconsciousness…”

“But first you will arrange my affairs?” Geißler laughed heartily.

“There is nothing more to arrange. You also have not a glimmer of your circumstances. Your whole fortune is at most three thousand marks.”

“Well. Then I will come to you tomorrow; you can give me the money tomorrow, can’t you?”

“I will see.”

Falk suddenly thought.

“You actually need to give me only five hundred, the rest you will send monthly in hundred mark installments to this address.”

He wrote Janina’s address. “Who is that?” asked Geißler.

“Oh, an innocent victim of a villainy.”

“So, so… You probably want to go into the desert now and fast?” “Perhaps.”

Falk smiled. He suddenly remembered his role and began to laugh with exaggerated cordiality.

“Just think, I asked very eagerly for you.” “Where then?”

“In a completely strange house. I wanted to mislead a spy and so I asked very loudly and with great emphasis for you on the second floor… But that is not interesting at all.”