OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

Chapter 19

After Semmelweis’s departure, the young Doctor Roskoschny succeeded him at the maternity clinic. This inexplicable step, which looked like a flight, infuriated Semmelweis’s friends the most. They had exerted all their power to support him, digging, pushing, and paving the way, even allowing themselves to be politely dismissed—and now this man simply ran off. True, the ministry had initially permitted him only phantom exercises, which was certainly a setback, but it wasn’t such a disgraceful slight that he couldn’t have endured it and waited for the ministry to reconsider. But to throw everything away and flee was not only foolish but also a humiliation for all those who had championed him. How did that leave them now? One almost had to doubt Semmelweis’s sanity. Now he was in Pest, rumored to be an unpaid honorary senior physician at Rochus Hospital—let him stay with his Magyars and see how he fares; no one would lift a finger for him anymore.

Professor Klein and his allies, however, rubbed their hands and remarked with regret that this confirmed their view of Semmelweis: a talented man, but clearly not quite right in the head. This incomprehensible resignation fit the overall picture—such a pity.

And now the young Doctor Roskoschny had taken his place. His father had once been the Freiherr von Reichenbach’s family physician; he hailed from Moravia, a backwoodsman, so to speak. His greatest effort was to erase that provincial stigma; the mark of his origins had to be obliterated. He aspired to be Viennese in essence, demeanor, behavior, and intellect, aligning himself in spirit with the city’s upper echelon. He had succeeded in gaining entry into noble and high-church circles—a driven young man, he enjoyed his superior’s favor. Professor Klein held him in high regard; this pupil shared the right judgment: Semmelweis’s views were unacceptable to science.

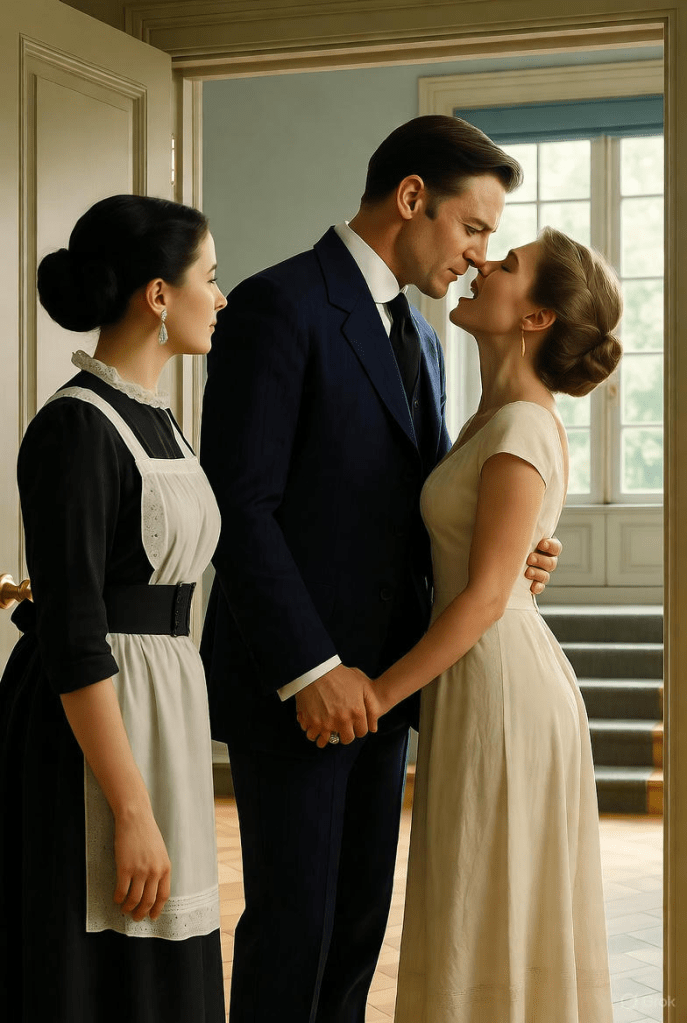

The only embarrassment was that Roskoschny found the Freiherr von Reichenbach’s daughter as a nurse at the clinic. She couldn’t bring herself to follow Semmelweis to Pest; she wanted to stay in Vienna and continue his work in his spirit. Oh yes, Roskoschny remembered well—Ottane, a little girl with bright eyes; they had played together as children. But now he was the doctor, and she was the nurse, and her mere presence was a constant reminder of that backwoods past. Moreover, aside from everything else, it would be entirely inappropriate to renew old ties with a family that had brought itself into public disrepute. Everyone spoke of the scandal in Reichenbach’s house; the sister had eloped and married a former barber’s apprentice and juggler. The furious letter the father had flung at her like a curse was in everyone’s hands. And this Karl Schuh hadn’t remained silent; he had responded with a pamphlet titled A Reckoning with Freiherr von Reichenbach, available in all bookstores. The Freiherr and the barber’s apprentice had publicly clashed, and moreover, Reichenbach had faced a resounding rejection at the Academy of Sciences—about as harsh as it could get.

No, it was better to have nothing to do with these people. What would they say in the high circles Roskoschny frequented about such an acquaintance?

Ottane sensed from the first glance how things stood with her new superior. She avoided undue familiarity, had no intention of embarrassing Doctor Roskoschny. Here, he was the doctor, and she the nurse—nothing more.

If she began to realize she couldn’t endure it much longer, that wasn’t the reason. Roskoschny’s refusal to acknowledge her was his affair. But he started dismantling Semmelweis’s legacy; he was a man after Klein’s heart, sharing his superior’s convictions. Semmelweis’s approaches were deemed excessive; his directives were ignored, and mortality rates rose.

The mortality rose. That was what Ottane couldn’t bear; it turned her work into torment and frayed her nerves to see the whimpering, groaning victims of medical arrogance. She resisted Roskoschny’s orders, adhering to what she’d learned from Semmelweis, and faced daily reprimands. As brave as she was, she couldn’t prevent nighttime attacks of weeping fits.

“If my treatment of the patients doesn’t suit you,” Roskoschny had coolly stated, “then you can leave.” She could leave, and she would—she knew that now—but she didn’t yet know where to go.

It was strange that on the day she reached this point, she would receive an answer. And it was Max Heiland who provided it.

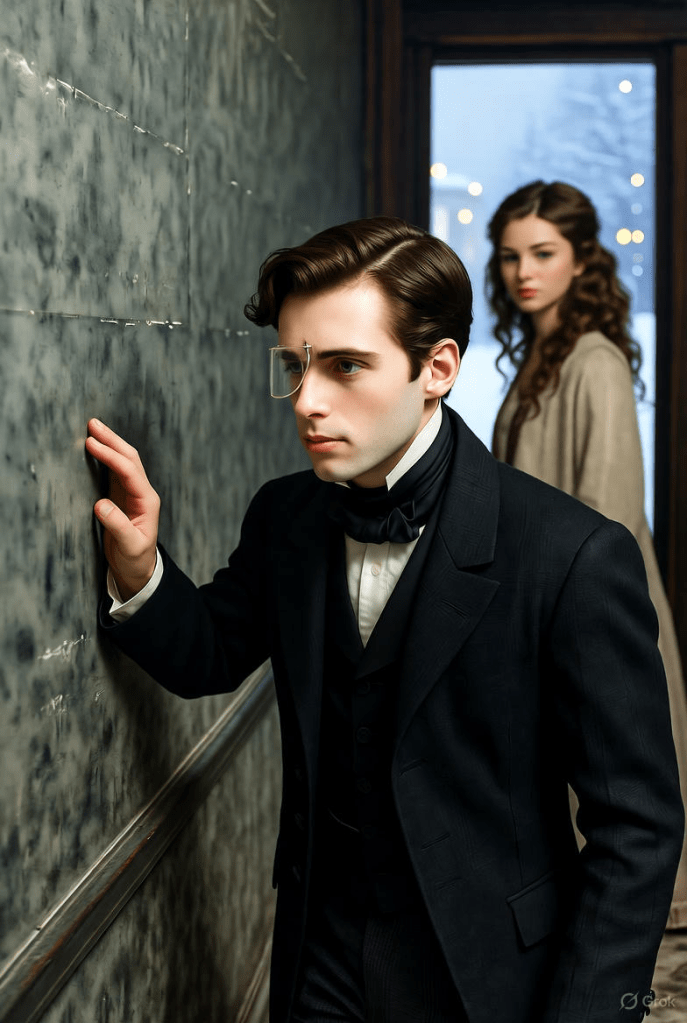

He arrived just as she returned from visiting her sister and headed to her room, walking down the corridor. Someone was coming down the hall, keeping close to the wall, occasionally feeling with his hand, placing his feet cautiously. A stranger, whom Ottane initially ignored, but then the stranger, almost past her, suddenly said, “Is that you, Ottane?”

So that’s what Max Heiland looks like now? He’s still as tastefully and fashionably dressed as ever—a handsome young man—but the fresh boldness has been wiped from his face. A crease runs across his forehead, another between his eyebrows, and in his eyes, now fixing on Ottane, there’s a slight cloudiness.

Ottane’s first instinct is to turn away, leave the man standing there. She could do so without self-reproach, given what he did to her. Surely he doesn’t come from an overflow of happiness, a world of love and devotion, a paradise of the heart—that’s evident—but it’s no longer her concern.

But then Max Heiland said, “Good day!” And: “How are you, Ottane?”

He said “Ottane!” and in that stirring tone, unchanged from before, Ottane felt she owed him a response. Well, how was she? She always had her hands full, but today she had time off; she’d visited her sister and would now resume her duties. She said nothing about the state of her work—Max Heiland didn’t need to know. Nor did she ask the usual counter-question about his well-being.

But Max Heiland began on his own: “I thought I should check on you. I’ve been to the eye clinic.”

“Oh?”

“Yes, something’s wrong with my eyes. I get these odd disturbances—gray spots, you know—and the outlines blur, and I can’t judge distances properly. They examined me thoroughly over there, with all sorts of devices…”

He smiled a little hesitantly, and Ottane’s heart, which she thought she’d calmed, suddenly began to beat hard and painfully again. Now she understood what that strange quality about Max Heiland might be.

“Well, and…” she asked anxiously.

“It’s nothing serious; it’s nerve-related. I’m supposed to to take it easy. No reading, no painting—best to go on a trip…”

“You should follow the doctors’ advice… you love traveling so much.” It was a small jab, and Ottane didn’t deliver it without thought. Here stood Max Heiland, and there stood Ottane, and it was just as well to set the situation straight with a little spite and raise a barrier between them.

But Max Heiland didn’t pursue it further; he smiled quietly, almost humbly: “Yes, certainly… it’s just… it has its difficulties… I don’t want to travel alone… and the doctor says I shouldn’t. It happens, you know… sometimes—only temporarily, but now and then—a veil comes over my eyes. Then I probably need someone…”

Ottane almost regretted her earlier jab. She felt a pang of sympathy rising within her and a desire to say something kind and balancing, but she hardened her resistance. No, Max Heiland didn’t deserve leniency or compassion; it was a matter of self-defense to keep all her defenses up against him.

“You have a companion!” she said bluntly and without mercy.

Max Heiland turned his head aside: “It’s over,” he said quietly.

“It’s over?”

“Yes, completely over, Ottane. I believe when fate wants to end something swiftly, it grants total fulfillment. Relationships between people that can withstand complete fulfillment are enduring, eternal from the outset; all others are mere attempts and illusions, a deceptive shimmer on the surface.”

There wasn’t a single false note in what Max Heiland said; Ottane had never heard him speak so earnestly before. And someone—perhaps Semmelweis—had once remarked that people with threatened eyesight begin to think more deeply about everything and grasp questions more profoundly.

“So it’s over?” she asked again, a chill running down her spine.