Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

Wölfchen stared at it, fat tears running down his cheeks. But he

lit another cigarette when the first one burned down, removed the stub

from the frog’s throat and with shaking fingers pushed the fresh one

back into its mouth. The frog swelled up monstrously, quivering in

agony, its eyes popping out of their sockets. It was a strong animal

and endured two and a half cigarettes before it exploded.

The youth screamed in misery as if his own pain were much

greater than that of the animal he had just tortured to death. He sprang

back as if he wanted to run away into the bushes, looked around and

then quickly ran back when he saw that the torn body of the frog was

still moving. Wild and despairing he crushed it to death with his heel

to free it from its misery.

The Privy Councilor took him by the ear and searched his

pockets. He found a few more cigarettes and the boy confessed to

taking them from the writing desk in the library. But he could not be

moved to tell how he had known that smoking frogs would inflate

themselves until they finally explode. No amount of urging worked

and the rich beating that the professor gave him through the garden

didn’t help either. He remained silent.

Alraune stubbornly denied everything as well even after one of

the maids declared she had seen the child taking the cigarettes.

Despite everything they both stuck to their stories; the boy, that he

had stolen the cigarettes and the girl, that she had not done anything.

Alraune stayed at the convent for one more year. Then in the

middle of the school year she was sent home and certainly this time

unjustly. Only the superstitious sisters believed that she was guilty

and just maybe the Privy Councilor suspected it a little as well. But no

reasonable person would have.

Once before illness had broken out at Sacré Couer, that time it

had been the measles and fifty-seven little girls lay sick in their beds.

Only a few like Alraune ran around healthy. But this time it was much

worse. It was a typhoid epidemic. Eight children and one nun died.

Almost all of the others became sick.

But Alraune ten Brinken had never been so healthy. During this

time she put on weight, positively blossomed and gaily ran around

through all the sick rooms. No one troubled themselves over her

during these weeks as she ran up and down the stairs, sat on all the

beds and told the children that they were going to die the next day and

go to hell. While she, Alraune would continue to live and go to

heaven.

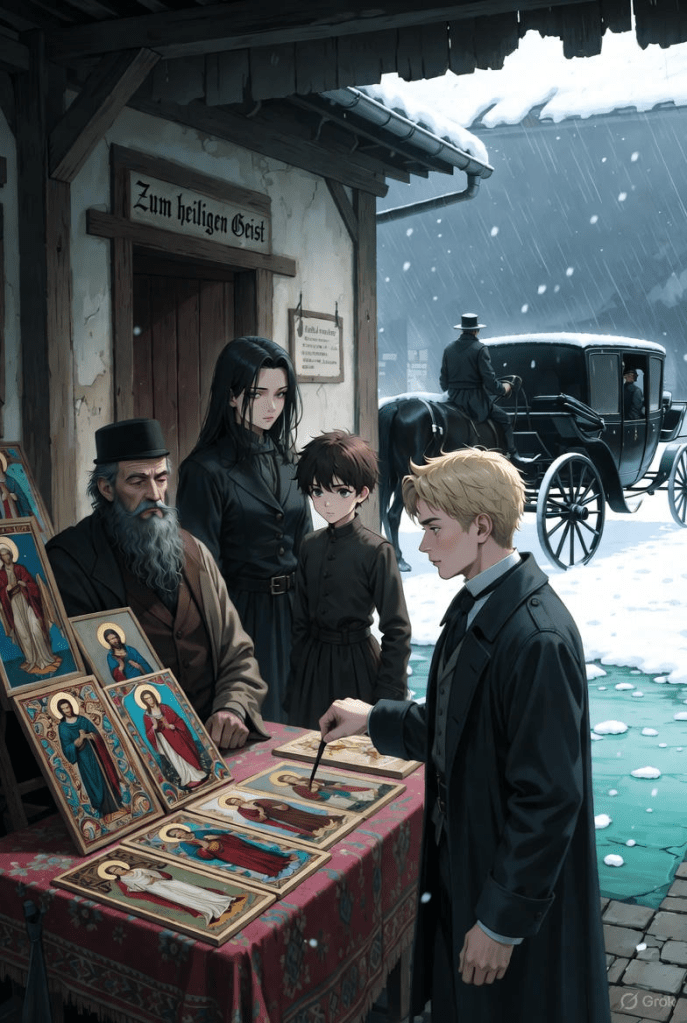

She gave away all of her pictures of the saints telling the sick

girls that they could diligently pray to the Madonna and to the sacred

heart of Jesus–but it wouldn’t do them any good. They would still

heartily burn and roast–It was simply amazing how vividly she could

describe these torments. Sometimes when she was in a good mood

she would be generous. Then she would promise them only a hundred

thousand years in purgatory. That was bad enough for the minds of

the pious sick little girls.

The doctor finally unceremoniously threw Alraune out of the

rooms. The sisters were absolutely convinced that she had brought the

illness into the convent and sent her head over heels back home.

The professor was tickled and laughed over this report. He

became a little more serious when shortly after the child’s arrival two

of his maids contracted typhus and both soon died in the hospital.

He wrote an angry letter to the supervisor of the convent and

complained bitterly that under the existing circumstances they should

have never sent the little one back home. He refused to pay the tuition

payment for the last half of the year and energetically insisted that he

be reimbursed for the monies he had put out for his two sick maids–

From a sanitary point of view the sisters should not have been

permitted to act as they had done.

His Excellency ten Brinken did not handle things much

differently. While he was not exactly afraid of contagion, like all

doctors he would much rather observe illness in others than in his

own body. He let Alraune stay in Lendenich only until he found a

good finishing school in the city. By the fourth day he had already

sent her to Spa, to the illustrious Institute of Mlle. de Vynteelen.

Silent Aloys had to escort her. As far as the child was concerned

the trip went without incident but he did have two little incidents to

report. On the train trip there he had found a pocket book with several

pieces of silver and on the trip back home he had slammed his finger

in the compartment door of the car he was riding in. The Privy

Councilor nodded in satisfaction at Aloy’s report.

The Head Mistress was Fräulein Becker who had grown up in

the University City on the Rhine and always went back there on her

vacations. She had much to relate to the Privy Councilor over the

years that Alraune stayed with her.

Right from the first day that Alraune arrived in the ancient

building on Marteau Avenue her dominion began and it was not only

imposed on her schoolmates. It was also imposed on the instructors,

most especially over the Miss, who after only a few weeks had

become a plaything for the absurd moods of the little girl, without any

will of her own.

At breakfast on that very first day Alraune declared that she

didn’t like honey and marmalade and much more preferred butter.

Naturally Mlle. de Vynteelen didn’t give her any. It was only a few

days until several of the other girls began to crave butter as well.

Finally a large cry for butter went up throughout the entire Institute.

Even Miss Paterson, who had never in her life enjoyed anything

with her morning tea other than toast with jam suddenly felt an

uncontrollable desire for butter. So the principal had been obliged to

give in to the demand for butter but on that very same day Alraune

acquired a preference for orange marmalade.

In response to the Privy Councilor’s pointed question Fräulein

Becker declared that the torturing of animals never came up during

those years at the Vynteelen School. At least no incidents had ever

been discovered. On the other hand, Alraune had made the lives of the

other children miserable as well as those of all the instructors, both

male and female.

Especially the poor music instructor who always placed his

snuffbox on the mantel in the hall during class so he would not be

tempted to use it. From the moment of Alraune’s entrance into the

school the most remarkable things had been found in it. For example,

thick spider webs, wood lice, gunpowder, pepper, writing sand black

with ink and once even a chopped up millipede. Several girls were

caught doing it and punished–but never Alraune.

Yet she always showed a passive resistance toward the musician,

never practiced and during class laid her hands in her lap and never

raised them to play an instrument. But when the professor finally

complained in despair to the principal Alraune quietly declared that

the old man was lying. At that point Mlle. de Vynteelen personally

attended the next hour and saw that the little girl knew her lesson

exquisitely, could play better than any of the others and showed a

remarkable talent.

The Head Mistress reproached the music instructor heavily. He

stood there speechless and could say nothing other than, “But it is

incredible, incredible!”

From then on the little schoolgirls only called him “Monsieur

Incredible”. They called after him whenever they saw him and

pronounced the words like he did, as if they didn’t have any teeth in

their mouths either.

As for the Miss, she scarcely ever experienced a quiet day. New

stupid pranks were always being played on her. They sprinkled itch

powder in her bed and one time after a picnic placed a half dozen

fleas in it. Then the key to her wardrobe was missing, then the hooks

and eyelets were torn from the dress that she wanted to wear. Once as

she was going to bed she was almost frightened to death by an

effervescent powder reaction in her chamber pot. Another time so

many stinging insects flew through her open window that she

screamed out for help. Then the chair she sat on was smeared with

paint or with glue or she found a dead mouse or an old chicken head

in her pocket.

And so it merrily continued, the poor Miss could hardly enjoy an

hour of her life. Investigations took place and those girls found guilty

were always punished but it was never determined to be Alraune even

though everyone was convinced that she was the mastermind behind

all the pranks.

The only one that angrily rejected this suspicion was the English

woman herself. She swore the girl was innocent up until the day she

left the de Vynteelen Institute.

“This hell,” she said, “only shelters one sweet little angel.”

The Privy Councilor grinned as he noted in the leather volume,

“That sweet little angel is Alraune.”

As for herself, Fräulein Becker related to the Professor that she

had avoided coming into contact with the strange little creature from

the very start. That had been easy for her since she was mostly

occupied in working with the French and English students. She only

had to instruct Alraune in gymnastics and sewing. As for the latter

subject, she had quickly exempted her from it when she had seen that

not only did Alraune have no interest in sewing, she showed a

downright aversion to it.

But in calisthenics, which by the way Alraune always excelled

in, she always acted as if she never noticed the joking around the

child did. She only once had a little confrontation with her and that

was just after Alraune’s entrance into the school. She had to confess

that unfortunately Araune had gotten the better of her.

By chance she had overheard Alraune telling her schoolmates

about her stay in the convent. The boasting and cheeky bragging was

so abominable that she took it as her duty to intervene. On one hand

the little one told how splendid and magnificent the convent was and

on the other hand she told truly murderous stories about the various

misdeeds of the pious sisters.

She herself had been brought up in the Sacré Couer convent in

Nancy and knew very well how simple and plain it was and knew as

well that the nuns were the most harmless creatures in the world. So

she called Alraune into her office and reproached her for telling such

fraudulent stories. She also demanded that the girl immediately tell

her schoolmates that she had not been telling the truth. When Alraune

stubbornly refused, she declared that she would tell them herself.

At that Alraune rose up on her toes, looked straight at her and

quietly said, “If you tell them that, Fräulein, I will tell them that your

mother has a little cheese shop in her home.”

Fräulein Becker confessed that she had become weak and given

in to a false shame. She let the child have her way. There had been

something so deliberate and calculated in the soft voice of the child in

that moment that she had become afraid. She left Alraune standing

there and went to her room happy to avoid an outright quarrel with the

little creature.