Archive for January, 2026

Gaia as Master Power Source

Posted in Uncategorized on January 20, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 246- 249

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, fiction, love, short-story, writing on January 20, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

Only when complete silence had fallen in the background

he leaned back in his armchair, so that the blue-white-red sash

wrapped around his body tightened, took a sheet of paper from

the table, as if playing, and said with a singing and theatrical

voice:

“Citizen Anastasia Beaujonin!”

Loud murmuring, throat clearing and spitting out behind

us betrayed the now beginning tension of the audience.

The young woman next to me had let out a small scream

at the mention of her name. She stood up, burst into a new

torrent of tears and pressed a tiny handkerchief to her eyes. I

looked at her pityingly. Her pretty dress, pink and blue

flowered, was badly wrinkled and disfigured. Several times she

ran with her hand, smoothing out the wrinkles. Surely the

appearance of her person preoccupied her just as much as the

concern about the outcome of a trial that knew neither

witnesses nor in its deliberate brevity offered little hope.

The chairman assumed a significant posture, made a

beautiful gesture with his right hand, and spoke with an

emphasis as if he wanted to declaim:

“Pay attention to what I say, Citizen Beaujonin! Think

about your answers, because our time is short. It does not

belong to us, but to the nation. You are accused of keeping

Baron Hautecorne hidden in the attic of your house for three

days although you must have known that he belonged among

the proscribed. What do you have to reply?”

“Oh, my God,” the woman stammered. “I loved him so

much — -“

The judge smiled. From behind one heard a coarse

woman’s voice:

“She is brave, the little one, and speaks as a woman

should speak.”

“Silence, Mother Flanche!” shouted the judge. “You must

not make any remarks here!”

“Don’t break anything, my sweet boy!” it came back. “I

have known you since you were a Temple singer.”

The chairman was about to start up, but then only made a

dismissive gesture with his hand and said, turning to the young

woman, “So?”

She swallowed a few times and directed her shy, fearful

gaze on me for a moment, as if she were trying to get courage

from me. This seemed to annoy the judge, because he took a

petition and knocked violently on the table with it.

“And why did you love citizen Hautecorne so much?” he

asked mockingly, showing his white teeth.

“Because he was so beautiful-almost as beautiful as

you!” She said softly, looking at him with a full gaze.

A storm of applause, mixed with shouts, laughter and the

trampling of feet roared through the hall.

Even the committee members smiled sourly, and the

chairman stroked back a curl of hair that had fallen across his

forehead with a smug movement.

“Let the little girl go – -,” cried one.

“She needs her head to give it to you-,” they laughed.

“Well said, Rodolphe.”

“She knows how you men must be treated.”

When silence had returned, the Judge said in a gentle

voice:

“Madame, I have reason to believe that you were

unaware of the danger of this enemy of the Republic when

your assistance was rendered?”

“Oh – no,” sobbed the accused, quickly grasping her

advantage. “I love the Republic -. I would have never –“

“Did he at least do his thing well, your baron?” roared

one of the audience.

The judge struck the butt of the file angrily.

“Hey, now, Perrin, Verrou, and Mastiche, see who’s

trying to make my acquaintance back there!” he shouted, and at

once three soldiers stumbled into the background, their heavy

rifles in their arms.

Immediately there was silence.

The judge leaned toward the committee members. They

whispered and nodded to him.

“Madame,” then said the presiding judge, “I will dare to

set you at liberty for the time being. But take care!”

“Oh -” the woman cried out and laughed all over her face.

“Wait Madame. I want to take it upon myself. I have a

responsibility to answer to the nation. You see, the people are

mild and chivalrous to women, if that is possible. Before you

leave you will have the goodness to write your future address

on a piece of paper and hand it to me!”

“Oh, you damned truffle pig,” laughed one of them. The

soldiers spoke fiercely at him.

“I’ll say no more,” he assured them. “Let go of my

paws!”

Silence fell again.

The little girl smiled gracefully, pattered on her high

heels to the tribune table and scribbled a few words on a piece

of paper, which the judge held out to her, read and pocketed.

Suppressed laughter in the auditorium accompanied this action.

“You may go, Madame, but you will remain at the

Tribunal’s disposal!”

The woman stopped, looked sheepishly and uncertainly

at the judges and then at the laughing spectators, turned

suddenly and ran quickly, looking neither to the right nor to the

left, right through the middle of the dumbfounded looking

soldiers and out of the room.

Immediately, the chairman assumed a dreadful official

face, rustled with paper and then said briefly and sharply:

“Citizen Melchior Dronte!”

I stood up.

Everything in me was calm, all fear disappeared. Again, I

felt as if I were now contemplating a fate, whose further

development was completely clear to me. Without any hostility

I looked at the vain man who had set himself as a judge over

me. His gaze immediately met mine and passed me by. In order

to hide this weakness, he took his eyes off me and taking some

sheets from the table acted as if he needed a constant insight

into the act, which would explain the circumstances of my

capture and the charges against me.

At last he raised his head and said:

“In the case of an expression of the will of the people,

which was directed against the rightfully detested citizen

Lamballe —“

A many-voiced outburst of rage arose.

“Death to the aristocrat! Down with her!”

“Shut your mouths!”

“She’s already perished!”

“Death to Lamballe!”

The judge waited patiently for the noise to subside, and

then continued:

“- The detested citizen Lamballe, from whom important

information about a conspiracy in England against the republic

were to be hoped for, has been crushed by the holy wrath of the

citizens. You, citizen Dronte, have made the attempt to obstruct

the people, who were passing and carrying out its judgment.

What were your intentions with the way you handled this?”

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 240- 245

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged bible, books, fantasy, fiction, writing on January 19, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

“At the risk of disturbing your meditations, I would like

to ask you, with your kind permission, a few more serious

questions, the answers to which I am very anxious to hear.”

With a quiet unwillingness I tried to recognize the facial

features of the interrupter. But I could only determine that he

was no longer young and that his white and very narrow hands

were folded around his knee.

“I am glad to be at your service,” I said quietly, so as not

to disturb the deepening silence.

The unknown man moved with his stool close to me and

whispered, as it seemed to me, in some agitation:

“All of us, who are here, so far as human calculation is

correct, will be sentenced to death in a few days. In the

certainty that our life, which would lead anyway to annihilation

will now be completed more quickly than nature demands,

there is nothing frightening for me. Another question worries

me, my lord. What happens, when the path of life, which leads

from the brain to the most distant and smallest parts of the body,

is cut by the axe?”

“Any doctor can tell you,” I answered.

“What happens is what we call death.”

“What we call it!” hissed the stranger close to me. “But

have you never heard that the severed heads are still alive? Do

you know that they move the eyes, the hairs stand up straight

against the walls of the basket? That they look in the direction

of the caller, when their name is called, and form clearly

recognizable words with their lips when they are asked? How?

Come to me, esteemed one, but not with Doctor Galvani’s frog.

Here we are talking about the ability to think, to be conscious–

“

“The problem is idle in a higher sense,” I said, “even if

we assume that the cut-off head still thinks and tries to act, this

lasts only a few seconds as a result of the lack of blood supply.

Then the standstill is there.”

The man slid his stool even closer.

“Good, good,” he said excitedly. “Let’s not bother with

that. It is indeed of little importance. What however, is death?

Is it the death of the body and the freedom of the soul, or are

the body and the soul so much together that one dies with the

other? Can you give me a comforting answer?”

The last words sounded like a plea. It had become

completely quiet in our dungeon, and nothing could be heard

but the stomping of the guards in front of the windows and a

soft whistling, the breath of the sleepers.

“Since you seem to be interested in the opinion of a

stranger, I will answer you. Now then, my dear Herr, I believe

that after death, the soul is separated from the body and enters

the eternal life from which it comes,” I said in a muffled voice.

He shook his head vigorously.

“The priests of all creeds say such things. But no one can

imagine what they are really saying. What do you mean:

Return to eternity? Without the artful apparatus of the brain,

the soul is incapable of expressing itself. What becomes of it?

A vortex of air, a cloud of smoke, transparent ether? Where

does it go?”

“It goes into a new vessel.”

I felt as if someone else was speaking out of me. I had

never thought this thought, and yet now it was there as if I had

always carried it within me.

The other laughed unwillingly.

“Into a new vessel, that is, a new body! Here is already

the absurdity. The number of departed are so great that not

even a thousand of them can find a new home.”

I listened to the inner voice.

“Whoever can preserve the consciousness of his earthly

existence beyond death will be reborn in a human body. That is

my belief.”

“And if it succeeds – how often would such a return have

to take place?”

“As often as needed until the soul is purified,” I replied,

moved.

“And then?”

“Then the soul rests consciously in God.”

The man struck his knees with his fist.

“Always the same old stories! Purified! Pure! And the

hatred? The burning greed for revenge, the rage beyond the end,

the hope to retaliate a thousand fold?”

“These are all impurities that must fall off,” I repeated

what my inner voice said. “In the purification of purgatory -“

“Purgatory?” he cried out. “You talk like a Catholic priest.

Where is it supposed to be, this fabulous purgatory?”

“Here, it is life. Life in human form or -“

“Or?”

“Or in the body of an animal,” I said, and saw in my

mind’s eye how tears were streaming from the parrot’s ugly

spherical eyes.

“But these are theories. I want certainty -“, my late

companion insistently demanded.

“There is only one certainty: that of feeling.”

“Faith, then, my lord.”

It was I who spoke thus.

“Fairy tales, my lord, fairy tales. I will tell you what is

after death: nothing is. And that’s the terrible thing, this

extinction of being. To have never been! It is horrible. And I

don’t need to believe in it. I know it.”

“I’m sorry I couldn’t bring you more comfort,” I said, and

was seized with intense pity.

“It is my fault,” he defended me politely. “A few days

ago I spoke to ‘Abbe Gautier before he was executed. An old

man with white hair, a worthy priest. He was struggling to find

a hunchbacked quack- who had been convicted of common

crimes, and pointed him to the infinite, eternal goodness of

God. But the Italian with the hump would have nothing of it

and kept shouting:

“Niente! – Finito -nulla. Nix immortalita – o Dio, Dio!”

“Then why did God call upon him?” I asked.

“Out of habit, I guess. That good Abbe Gautier said about

the same thing as you. I envy him and you. Sleep well!”

He slipped into a dark corner with his stool. I heard him

sigh deeply.

A bunch of keys jingled. The iron door creaked open.

The sleepers groaned unwillingly, turned around, and muttered

unintelligible words.

A turnkey, carrying a large, dimly burning lantern,

entered, and followed by a commissar with a tricolor sash.

Carefully he examined the paper that the official had handed to

him, and then called out half aloud:

“Citizen Dronte!”

I stood up and saw the commissar make a violent

movement of surprise or of joy. He took the lantern from the

overseer’s hand, motioned for him to stop at the door, and came

quickly towards me.

“I am Commissar Cordeau!,” he said hastily and quietly.

It was Magister Hemmetschnur whom I had taken from

Krottenriede.

“I can only stay for a minute,” he repeated in a

monotonous, indifferent voice, while the lantern in his hand

clinked and trembled.

“I went to all the prisons when I found your name on the

list. This is the last one. I know everything. As many of the

cursed Aristocrats I have sent to the Orkus. I would go back to

being the poor miserable Hemmetschnur on Krottenriede if I

could save your noble life, which is so dear to me. Do not

move, do not speak. There are spies in every dungeon, even

here. I’ve spoken to the chairman of your tribunal. The charge

is false. It was not your intention to free Lamballe, but rather as

a loyal supporter of the Republic, you wanted to prevent the

ignorant people from a rash act through which the discovery

and exploration of the dangerous plans in which the princess

was involved are now forever impossible to determine. They

will believe you. You were providing an important function

that will protect you forever. Do not move your head. You must

accept. Otherwise, you will be lost. If you have not understood

me, clasp your hands together as if pleading. You don’t? So you

have understood everything. Now a necessary comedy begins.

Do not be frightened of me, who would like to kiss your hand.”

And with a loud voice he continued, “So you refuse? You want

to know the whereabouts of the escaped traitor? Good. You will

stand in front of your judges tomorrow. Don’t forget that the

lictors’ bundle also contains a hatchet.”

Seemingly angrily, he stomped up and waved at the

turnkey.

“Citizen Gaspard! You’re liable to me for this dangerous

person!”

The turnkey shone his light in my face and grinned:

“This head is loose! I’m getting the hang of this thing,

Citizen Commissar!”

Laughing, the magister slapped him on the shoulder, and

they both left the dungeon. The door slammed shut with a thud,

the key rattled.

“Francois!” scolded one in his sleep. “See, which of the

cursed peasants drives over the inner yard.”

Then there was silence. The darkness dripped down like

pitch.

Before me in the darkness I saw the face of Isa Bektshi.

The kind gaze was directed at me. The narrow scar between the

eyebrows shone like the dawn.

“I will not lie,” I said to myself.

I saw nothing but the black night and I stretched out on

the thin straw of the floor to rest a little. After breakfast, which

the turnkey brought in on his board, a commissar appeared

with several soldiers and brought three of us, including me, to

the court session.

A young, pretty woman, who had mostly been sitting on

a cot, crying, and had received little notice by the ladies in my

prison, was brought in with me and a tall, very haughty looking

man in a dark blue, gold-embroidered jacket and white

stockings was led away. The name of my fated companion I

had not understood when I was introduced yesterday. The only

thing that struck me was the deference with which the

aristocratic prisoners had treated him, and his careless,

condescending manner with which he had spoken a few words

to this one, then to that one, while he hardly noticed me. I was

walking behind these two, the woman and the haughty man; I

was walking alone between two soldiers who had been

specially commanded to guard me. We were led through a

narrow, terribly dirty alley, in which all kinds of garbage rotted,

to an old building, over the archway of which fluttered the

three-color flag. Then we reached a corridor into a low, very

large room, and had to pass behind a freshly painted cabinet,

smelling of fresh oil paint and then stopped.

The inner elevation, in which I had spent yesterday

evening, was gone from me. The thought that this day was to

be one of my last lay heavy as lead on me and filled me with a

dull ache. Even the inanimate objects around me took on a

strange and unfamiliar ghostly form, and even the early

morning light that shone through the dirty windows had a

mysterious reddish glow.

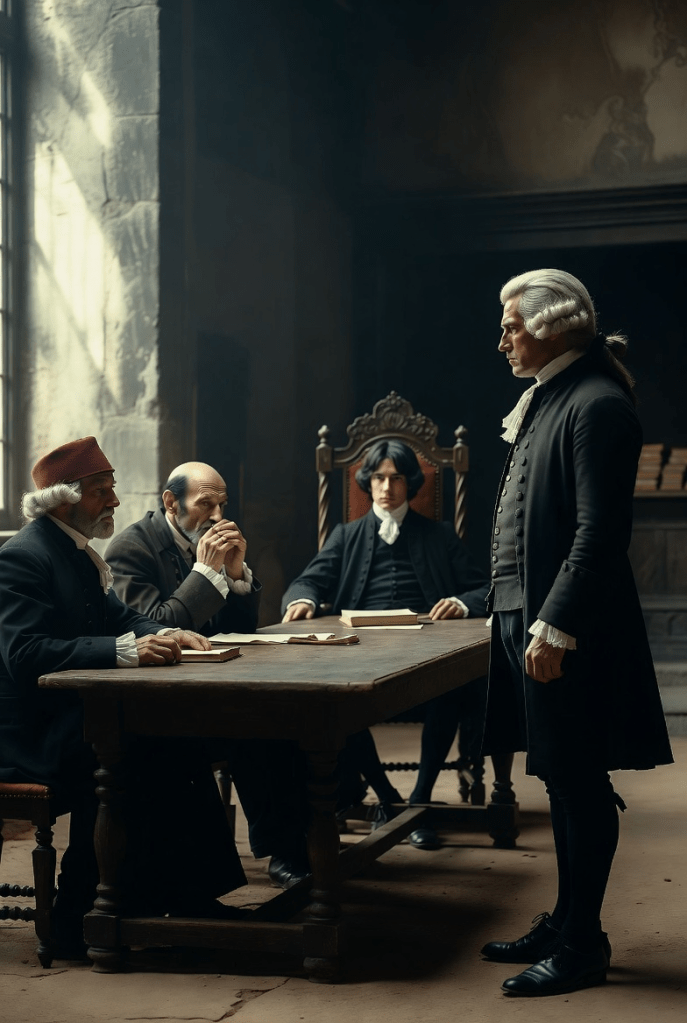

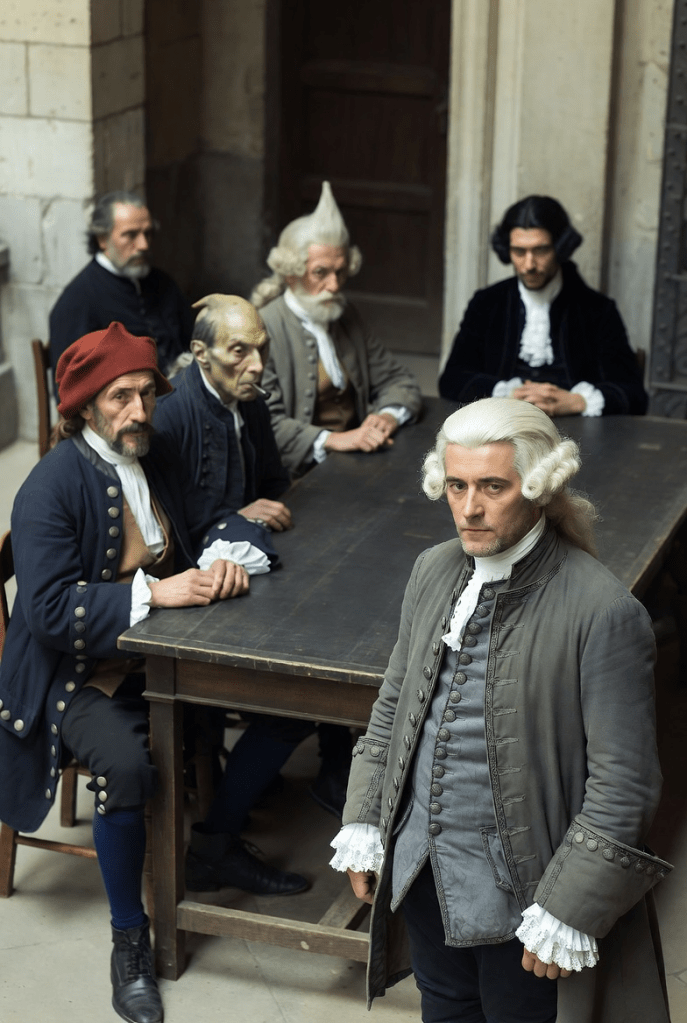

When a soldier motioned for us to sit down, I was given

the seat between the young woman, who from time to time

sobbed violently, and the gentleman in the blue jacket, who

looked before him with a stern and unapproachable face,

without paying any attention to anyone. Now and then he

would pull out of his pocket a gold can in the shape of a pear

and sniffed it with an extremely affected movement. In front of

us stood a heavy table with carved legs, on which everything

necessary for writing was piled up. On the walls lolled pale,

long-haired soldiers, some of them wearing wooden shoes on

their bare feet, and blowing foul-smelling tobacco smoke from

their lime pipes. They only changed their comfortable position,

when a rumbling drum roll outside the door announced the

entrance of the revolution tribunal.

We were compelled to stand and wait until the judges

were seated at the large table. I looked at the men who

presumed to decide on the duration of the lives of others. The

first at the table on the left was a craftsman with badly cleaned,

hands, whose imprint was visible on the rim of his red cap. In

the middle between him and a constantly coughing, obviously

sickly person with pointed, gray-yellow face, was enthroned a

black-haired young man of peculiarly impudent, but not

unhandsome appearance. His restless, dark eyes sparkled under

strong brows, and his long, carefully stranded hair under the

two-cornered hat hung down to his shoulders. He stretched his

legs, clad in white pants and boots with cuffs, far under the

table, waved to an acquaintance in the densely packed area in

the back of the room, and then rummaged with a pile of files

that lay in front of him. Then he spoke a few half-loud words to

the sitters and to the skinny clerk at the narrow end of the table,

propped his elbows on the tabletop, rested his chin on his

clasped hands and looked at us in turn with a look that seemed

to command the highest respect.

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 235- 239

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged family, fiction, life, short-story, writing on January 18, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

In the prison they must have long since heard the howls

of the insane crowd, because several times, inquiring and

peering faces appeared at the windows of the first floor. But

soon the obstinate shouting of the crowd was followed by

action; axe blows thundered against the small, heavy door, a

dusty pane of glass shattered under the thrown stones. Then a

window opened upstairs, a sleepy face with half-closed eyes

and sagging cheeks appeared, smiled and nodded to the people,

whereupon the shouting intensified to the point of madness.

Only for a moment my eyes were on a gray relief on the

wall, when a hurricane-like howling of many thousand voices

passed over men, the windows of La Force were shaking. The

small door opened-

In the stone frame stood pale as a corpse, a distorted

smile of fear in the beautiful face, her small hands raised as if

pleading, a young woman –

“Aglaja!” I cried out. It was her. Aglaja.

My beloved, slipped into the realm of shadows,

awakened from a deep sleep by the roaring of irritated animals.

There she stood, threatened by madmen, murderers, by

rusty weapons, stones, shaking -.

I screamed, screamed -.

Her blinding forehead opened in a red, gaping crack, her

eyes opened wide – from the light brocade of the bodice

suddenly rose a greasy, wooden lance shaft – Silk tore with a

high-pitched hiss — a small, plaintive cry – – like a bird call.

Flames fell from the sky, flared up from the earth, and

enveloped me.

I pushed and hurled people at people, smashed my cane

into a face, slammed my fist into a screaming mouth, sobbed,

screamed, kicked, grabbed the handle of a saber, struck so that

it sprayed, spitting and roaring louder than the thousands – –

My gaze was drawn tightly to a twitching, white body

adorned with blood roses, rough red laughter – I saw a dark

hand tugging at something long and pale pink, a naked black

foot kicked at a trembling woman’s breast —

A booming blow struck my head.

I fell. I tried to get up on my knees. Devilish faces

neighed all around me; in a wide mouth were greenish stumps.

In the hollow of two large hands, close to my face, moved

twitching a bloody piece of meat, shining red, terrible to look

at – a throbbing heart – I fell down on my face. In an unearthly

roar the world passed away.

The prison in which I found myself was an old coal cellar

and received only a faint light through the small windows,

which had never been cleaned. The bars in front of the

windows were thickly covered with street excrement, and the

yellowish glow left the background in complete dimness.

It took quite some time before the dull pain in my head

subsided to such an extent that I could look around in this

subterranean room. Again and again I felt the painful lump on

the back of my head, which a terrible blow had left behind, and

repeatedly I tried to remove my torn, bloody and covered with

street excrement suit in order to clean it. I was not indifferent to

my appearance because several ladies were present. They had

been given the largest part of the dirty wooden enclosure, and

some of the gentlemen who were also in the prison, who, at the

moment of their arrest, had an overcoat at the time of their

arrest, had disposed of this garment in order to be used as

blankets and bedding.

“May I ask your name, Herr?” a tall, impeccably dressed

gentleman in a poppy red jacket addressed me. “So that I can

introduce you to the others if that is alright with you.”

I named myself and was thereupon formally introduced

by the Vicomte de la Tour d’Aury to the other prisoners. I was

spoken to in an amiable manner with regrets that my so

desirable acquaintance had to be made on such a sad occasion.

I had unfortunately arrived in Paris several years too late, said a

very pretty lady with a little beauty spot on her white and rosy

face, and it was more than deplorable that under the present

circumstances, one must get a completely wrong impression of

the French way of life.

With a bow, I replied that the setting in which people are

found is not as important as the fact that people find each other,

and that I had already experienced in just a few moments so

many pleasant acquaintances, I had been abundantly showered

with chivalrous attentions on the part of my accidental

comrades in destiny.

Asked about the cause of my arrest, I could not avoid

mentioning the murder of the poor Princess Lamballe in the

gentlest form. The ladies immediately burst into tears, and

several gentlemen, with clenched fists, expressed the ardent

desire for unprecedented revenge. To all, however, the sudden

death of the beautiful woman on whose energy they had placed

great hopes was a heavy blow, which destroyed a large part of

their secretly cherished expectations. Now all their wishes were

directed to a terrible and bloody retribution, while two floors

above, it was surely decided to send the heads in which such

plans flourished, into Samson’s wicker basket.

The tremendous mental shock into which the

resemblance between the slain princess and my beloved one,

who was always fleeing into the shadows of eternity, had given

way in this prison to a feeling of desolate emptiness. And

secretly blossomed in me, like a pale Asphodelos, the longing

for the beloved image, which approached me in all kinds of

forms, leaving me to follow into the unexplored realm, where

her eternal home was. Without any excitement I thought of the

probability of my end. The hand on my pocket watch, which I

found in my vest with the glass broken, measured the last hours

of my life in the circle of numbers. For a long time I watched

the Arabic numerals on the white disc, adorned with a wreath

of cheerful roses, and thought that by one of the sixty strokes,

or between two of them, a sharp, short pain would fly through

my throat and extinguish my thoughts. With unheard-of clarity

I saw my headless torso in this badly battered brown suit lying

and twitching on the board, with two intermittently leaping

fountains of blood in place of the head, and this roll into the

basket of the Executioner. I looked at this shuddering self-

image so calmly, as if the thing didn’t concern me at all.

The addiction of the ladies for entertainment also in the

present place of stay soon snatched me from this sinking, and I

was compelled to answer all sorts of questions about my early

life, my adult life, my family and any adventures I might have

had in Paris. With graceful ease things were touched upon of

which I had not been accustomed to speak of for a long time

and whose description was embarrassing to me. But I soon saw

that the interest of the women was not as insistent as one would

have expected from the graceful eagerness of the questioning.

Everything that was done and talked about here had only

one purpose, to fill the gloomy and hopeless days that lay

before the sad end in the most distracting and entertaining way

possible. Some gentlemen dressed in the office of the maitre de

plaisir immediately offered, if someone covered himself in a

thoughtful silence, everything they had to dispel the contagious

gloom. They danced minuets and gavotte, practiced the almost

lost pavane, sang, arranged games of forfeits and blind man’s

bluff, played a little music and excelled in piquant anecdotes

and joking questions. This way of getting through the slowly

creeping time, I did not like much in my serious mood, but I

also accepted it. Even more unpleasant were the pleasures of

longing of a young count, who, with many sighs of regret for

the time when one of his distinguished relatives in Normandy

to pass the time had shot a rooftop worker from the castle tower.

Another gentleman who seemed to be of the same mind as him

praised the glory of the days when a member of his family had

been invited by Louis the thirteenth to a feast, and when, after

the hunt, his feet were frozen the bodies of two peasants were

cut open on the spot so that he could warm his cold feet in

them.

With such speeches, I did not know what I should marvel

at more: the blindness of people who even thought of such

conditions of existence, or the unspeakable patience of the

people, who had remained subject to such extremes, the taking

away of the last piece of bread. Despite my disgust against the

beasts of the street it became obvious to me once again that in

this country under horrible convulsions and according to laws,

which only God knew, a necessity was taking place, which was

nothing other than the consequences of the causes for which

these two thoughtless ones still mourned. The tender women in

this dungeon, the old men, among whom was the Count

Merigno, who was known for his charity, I felt sorry for most

of them with all my heart. But among them were also those

people who had nothing but a conceited disdain and insolent

contempt for those who were not noble born, who had no

knowledge of neither the sciences nor the arts and didn’t think

of anything at all, unless in the service of their indulgent and

gallant needs; their fate could not be called unjust. And I felt

strangely solemn and peculiar, when I discovered on the wall,

written in red chalk, the words: “Counted, weighed and found

too light.

In the late afternoon hours, when the room became more

and more relaxed, the outlines of all things blurred and only a

small candle stump burned in one corner, laughter and speech

gradually lowered. Several who seemed to be familiar with

each other, whispered all sorts of things that were not meant for

the general public. The wretched food in the unclean bowls,

which two turnkeys carried in on a board was, as far as it was

noticed, quickly gulped down, and the empty vessels were

taken away as they had come. After this many stretched out

with sighs on the plank beds or on the brick floor to escape into

the freedom of dreams and others, whispering prayers, moved

their lips and let the beads of the rosaries they had brought with

them slide through their fingers.

I had sat down, tired and with my head still aching, and

by stroking with my finger tips, tried to reduce the lump that

had been left by the blow, the force of which had caused me to

fall. Then, out of the groups, unrecognizable in the twilight, a

man emerged, carrying a stool in his hand and sat down on it

with me.

Anarchist Knight Apprentice: Chapter 20 A Christmas Gift

Posted in Uncategorized on January 17, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 230- 234

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, fantasy, fiction, short-story, writing on January 17, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

Despite the smallness of his body, there lay in his whole

posture something respectful and compelling, which was

difficult to escape from. Thus, his appearance captivated me in

the highest degree. He wore a very simple uniform unknown to

me, and had his arms crossed over his chest.

“You’re a stranger?” he addressed me, smiling barely

perceptibly.

“I am a German,” I answered him.

“Ah, a German!”

He nodded his head.

“A fine people, clever, warlike and obedient at the same

time. Excellent soldiers. You witnessed these executions, mein

Herr?”

In spite of the danger that such frankness could bring me,

I did not hide my disgust from him.

“Yes, yes,” he smiled gloomily, “By the actions of these

beasts you must have formed an excellent opinion of the

French nation. But that doesn’t do anything. These people are

good. Only they have a fever at this moment. They will cure it;

let it bleed a little -“

I hesitated to answer him, even though there were no

listeners nearby. For I was well aware of the fact that the so-

called Well-being Committee maintained numerous agents,

whose task it was to listen to the speeches of the people and to

induce the discontented to make statements, the reproduction

of which provided the means to render them harmless. But

immediately afterwards I was ashamed of a suspicion over

which this man was certainly above. As far as my knowledge

of man, I read in this face ruthlessness, indomitable will, and

the power to remove unpleasant obstacles by force. Perhaps the

little man with the hard mouth was capable of a gigantic

despicability when his certainly unusual plans required it, but

hardly of a petty action against someone whose path did not

cross his. All this I read in the dark abyss of his eyes, from

which shone the spark of a genius.

“I deplore it,” I said to him, “that bloodlust and

vindictiveness sully the garb of the goddess of liberty, and that

it is precisely the ugliest drives that are the shoots that appear

most conspicuously in the disintegration of a fixed order. Thus

it happens to me that what seems great and sublime to me from

a distance, appears frightening and devoid of all greatness up

close. The freedom of a people –“

“Oh, freedom!” he interrupted me. “Those are silly

phrases. The people do not need Freedom, but the firm hand of

a leader. Centuries will pass before the people will be ready for

the ideals for which the unfounded enthusiasts believe the time

has already come. It does not do much harm, however. The

heads that are now falling are not worth much, except for a few

whose loss is deplorable, and the riffraff are in their own way

for the time being. Nevertheless, mein Herr German, I say to

you that with this very valuable, fiery and easily treated

material the world can be conquered, if it comes into the right

hands. Out of these lousy, jeering, broken lads an army of

heroes can be created like no other that has ever stomped the

ground. The monstrous body, unconscious of its strength lacks

only the head to make it insurmountable.”

“Surely this head also sits on mortal shoulders,” I replied.

“And it is, as you know, a bad time for heads.”

Again the man’s lips twisted into an almost perceptible

smile.

“I have good reason to hope that the head I mean will not

fall into Samson’s basket,” he said.

Slowly we walked in the direction of a side alley. Wild,

long-drawn out screaming and the wailing of a woman’s voice,

coming from an old house, made me stop. As we came closer,

we saw in the dark hallway a young woman in the labor of

childbirth lying on the brick pavement. Under her pain, new

life pressed towards the light. Neighboring women took care of

the woman in labor, and an old woman told us to unwillingly

go on.

“Fat Margot is having another baby! Every year she gives

birth to a piglet!” shouted an alley boy and danced on one foot,

delighted to be present at this event.

The officer grabbed the boy by the arm, turned him

towards him, looked him in the face with a terrible look and

said:

“Why are you pleased, cretin? Is it because your

replacement is born? He will take your place in the regiment

when you are buried in the clay after the battle!”

I saw the lad turn pale under the icy gaze of my

companion, as if he had seen the Medusa’s head. Shrieking and

flailing his arms, he ran down the alley.

I watched him go. When I turned around, the officer had

disappeared.

After that day, I did not go out much on the street.

Several times at night I heard the pounding of rifle butts at the

front doors, the wild weeping of women and the horrified

objections of those suddenly arrested who had been dragged

out of their beds.

My reclusive behavior noticeably increased the distrust

of the house inhabitants. Nevertheless, it was the hardest thing

for me to overcome, to enter the streets, where one could see

almost only drunken rabble and meddlesome women. One was

begged for, harassed in every way, insulted and suspected for

no reason.

But on this early autumn day there was such an

oppressive sultriness that the stay in my upper level room

became quite unpleasant. I chose my most inconspicuous

garment, the brown, already damaged travel suit, a simple rain-

soaked hat and a crude stick, to distinguish myself as little as

possible from those who spoke the big words in the streets. I no

longer wore my hair coiffed and powdered, but, according to

the new fashion, falling on the shoulders.

Today, too, the streets were full of shouting and partly

armed mobs. Recruits, adorned with bows and ribbons, were

marching off to the threatened frontiers, and the excitement of

the first days of September had increased still further.

Especially near the prison of La Force, all the scum of

Saint Antoine and other suburbs seemed to have gathered. The

closer I came to the small gate of the prison, the wilder the

raving, singing and shouting swelled. Ragged sansculottes-

radicals stood here, armed with pikes and rusty sabers, in dense

mobs and apparently waiting for something special. A

disgustingly overgrown man, who had a cockscomb like violet

growth hanging down over his left eye, as I could clearly

observe, sneaked around from one group of people to another

and everywhere spoke a few words, which were taken up with

ear-tearing howls. I deliberately placed myself in the vicinity of

such a confluence, in the midst of which a fury with flying

strands of hair wielded a butcher’s axe, and struggled to hear

what the people were so excited about. As soon as I arrived the

crooked monster started on the group and whispered:

“Citizens, do you want to see the aristocrat who will soon

come out of this prison door, escape to England once more?

She will help the fat Capet and the Austrian woman escape

from under your noses. Down therefore with the Intendant of

the Austrian whore! Down with Lamballe!” Unanimous

shouting announced that they were of one mind with him and

not one was willing to let the princess Lamballe go, who was

the subject of much talk at the time.

“Enough of this gossip, you with your violet growth on

your eye!” shouted a person thin as a skeleton. “We want to

make cocards out of her guts if she gets into our hands.”

“Let me, me!” hoarsely cried a wolf face with enormous

jaws and low forehead. “You are all worthless, overcome with

pity, when she puts on her little mask -“

“Hey, is your heart made of stone and do you have iron

veins, Ruder-Mathieu?” a sloppy woman laughed and pushed

the man to the side.

“Do you want to see Louis Capet’s souvenir, you

pavement kicker?” barked the guy, stretching out a hand

surrounded by blue-red rings of scars. “I wore his bracelet for

six years, here and on the back of my foot -do you think that

makes sugar daddies out of people?”

The smell of liquor, old clothes, and the smoke of bad

tobacco wafted around me along with the roar of laughter that

rose.

“Murderers of women. By the grace of the king,” a voice

said softly at my ear. “Look at the cattle, the forehead, the thick

eyebrows, the bit -“

“What are you whispering about, old fish-head?”

The galley convict shook his fist at the human beside me.

A small, stooped man quickly ducked into the crowd.

“Out with Lamballe! We want the intendant! Break down

the door! We want to have a close look at her, back and front,

just like her lovers!”

“The judges in there are asleep,” crowed the abomination

with the facial outgrowth. “We will wake them up!”

“Out with her! Make it snappy, you donkey heads in

there! Give her to us!”

In the roaring and pushing of the supremely heated

masses, in the midst of brandished sabers, knives, and lances, I

stood and gazed at the door as if paralyzed. I was afraid; a

devouring fear seized me, literally crushed me. It was an

indescribably horrible feeling, a feeling in which dark

knowledge was hidden. I knew what had to come unstoppably,

as if I had already experienced it all. A beardless, cheeky face

emerged inside me, a receding forehead sown with ulcers,

beneath sand-colored stubble hair. I looked around and

immediately looked into the middle of the face, which already

existed in my imagination. But I resisted, again and again and I

succeeded in pushing back the certainty coming from within

my inner being, without this effort of the will, I could have said

at any moment, blow by blow, what was going to happen now.

All this was like a dream within a dream yet of shuddering

physicality.

Anarchist Knight Apprentice: Chapter 28 Becca’s Initiation

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, fantasy, fiction, short-story, writing on January 16, 2026| Leave a Comment »

Chapter 28 Becca’s Initiation

He had left her in the darkness to meditate. Now he was coming back with her torch and her black clothing. Gruffly he told her to put the 2nd degree clothing on. She turned her back and stripped. He was watching her naked body. The bruises were healing, and he wanted her. Slowly she turned around and faced him. Her long red hair framed her breasts. She looked beautiful to him. He reached toward her, and they clung together, kissing as her body pressed against his. His lips sought hers desperately as hers sought his. His hands felt her body, and her scent was wonderful. They stopped and looked at each other.

“This isn’t in the script!” Tobal quipped.

She smiled and began putting on her 2nd degree clothing. They steadied themselves, stepping into the ritual’s next phase. Then they went together toward the main circle for the initiation. Things went well until Becca found herself surrounded by the six menacing, darkly hooded figures she was told she needed to fight. Tobal thought he went crazy at times during battle, but Becca was scary. With a scream of rage that shook him to his core, he watched as she mowed the six figures down like so much grass. She was obviously an advanced martial artist with an axe to grind, and she wasn’t holding anything back.

The first two got broken ribs before they knew what hit them. The first fell from a savage front kick that broke through his guard. In a smooth, fluid motion, a spinning sidekick disabled the second. The third was reaching for her and got a dislocated shoulder as he was thrown into a fourth that wisely stayed on the ground. A spinning backfist was already on its way to number five, and number six had his jaw broken with a deadly kick square to the face. It was all over in less than two minutes, and the only sounds in the cavern were the moans of the injured. For a moment, the cavern held its breath, her rage echoing.

Slowly, sanity came back, and Becca dropped on her knees to the floor, sobbing hysterically. Tobal dropped down beside her and put his arms around her, trying to comfort her. Then he gently helped her up and led her out of the circle and into a quiet corner where they just sat together in silence. He squeezed her hand as the medics took five of the six out of the cave to get medical attention. She started crying again, and he didn’t know what else to do except hold her tightly against his chest. Gradually she relaxed and fell asleep in his arms.

The circle had been disrupted, and several members milled around arguing with each other. Several red-cloaked figures appeared, and one approached them in the darkened corner. As the figure drew closer, Tobal saw that it was Rafe. He put his finger to his lips for silence and indicated that Becca was sleeping. Rafe looked at her thoughtfully, nodded, and turned back to the clustered group of medics. There was some kind of heated discussion in which Rafe was obviously taking part. Then several black-hooded Journeymen were called into the group, and preparations were made to recast the circle and begin Fiona’s initiation.

Becca slept through most of Fiona’s initiation but roused herself as six black-hooded figures surrounded Fiona in the center of the circle. Tobal felt her stiffen, and he gripped her in support. Glancing at him, she relaxed a bit but was still focused intently on what was happening to Fiona. She watched as each figure stood impassively until Fiona tried attacking them. Fiona was fast and dodged several attacks and landed a few of her own but did no real damage. She was also taking a slow beating as one of the hooded figures landed a blow that knocked her to the ground.

Gradually Fiona realized that no one attacked her unless she attacked first. She also realized that only one figure would fight at a time. When she realized this, she stopped fighting and just stood silently in the ring with her arms folded and her eyes glaring defiance.

As one, the circle began to move, and the drums sounded within the cavern, and Fiona’s initiation was completed to the sound of cheers and welcome. Then the High Priest raised his hands for silence.

“There is unfinished business in this circle tonight,” he said. “There are two initiates, and the second initiation must also be completed, and the new initiate welcomed into our group.”

He motioned for Tobal and Becca to come forward.

Becca was hesitant and resisted but continued at Tobal’s reassurance. He took her hand and gently led her into the circle and stopped in front of the High Priest.

The High Priest continued, “Becca, you were charged with the duty of defeating in combat six other Journeymen before you would be able to advance to the Master degree. The six that you fought tonight were supposed to be symbolic in nature, meant to test her spirit, not break her body, but your victories have been real. You have completed the Journeyman degree, but you cannot advance into the Master degree until one year and a day has passed. This is the minimum time requirement. All that remains is to give you the blessings of the God and Goddess of this degree.”

Then raising his hands, he turned to the circle and asked loudly, “Does anyone here dispute the claim that Becca has won her six victories and completed the work of this degree?”

There was stunned silence around the circle, and then some members started moving widdershins, dragging others with them, and soon the entire circle was spinning. The drums were beating, and people were leaping and laughing, yelling and clapping in approval as the initiation concluded, and the wildest party in Tobal’s memory began.

Later he moved over to where Becca and Fiona were talking together. Becca was smiling, and he hoped she felt like she was among friends. He gave her a hug and a smile, and she hugged him back and kissed him lightly on the lips.

“Thanks for helping me through the initiation,” she said.

His eyes twinkled, “Any time, it’s my duty.”

When Tobal woke the next morning, both Fiona and Becca were gone. He had no idea where they had run off to and was slightly disappointed. If they wanted to go off by themselves, it was completely up to them. Mumbling a bit to himself, he left to go find Jake for some sparring practice. After watching Becca take out those six guys last night, he felt he really had a few things to learn.

The End of Book One of the Anarchist Knight Trilogy.

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 225- 229

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, fantasy, fiction, short-story, writing on January 16, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

They had known how to prevent it, if one took them as

symbols of a caste, prevented people from reaching the heights

of a decent life. Again and again shoved the unfortunates into

their doghouses and holes, pressed them into the fronts, and in

shallow dalliance mocked the muffled cry from the depths. At

last, when even the excessively rich resources that had been

withdrawn from the others, ran out, they heaped up the grain of

the fields into locked barns, in order to sell sparingly and with

usurious profits to the starving, during the coming famine.

They had forced a painful bridle between the teeth of the

desperate and tightened the reins, while their whip tore bloody

weals. Thus the masses had now finally burst their bonds in

insane rage and torment, and the dull masses had acquired a

flaming will: the will to destroy, to slaughter, to tear to pieces

the wanton, the tormentors and to wipe them off this earth

forever. Who but knew how to read the people’s faces, in those

faces, in their ignorant and still astonished expressions, he

knew in retrospect that the power that had been shattered, if it

had been used with a little kindness, with wise prudence

humanity, would have endured for a long time and could have

achieved a bloodless, peaceful transition to a more just

distribution of goods. But so it was, as if these kings, dukes,

counts and rulers of all kinds had undertaken the ludicrous

attempt to see how long and to what extent they could torture

patient people, until they would finally rise up against the

burden of tortures. And yet I also felt sorry for them.

I was soon awakened from my thoughts by the senseless

and agitated pushing after me of those who also wanted to be

part of the sad procession.

I was startled when, with a jerk, everything stopped and

the people flowed apart. We had arrived at a not too large

square surrounded by old, steeply gabled houses with

blackened walls; my feet almost sank in a sticky, dark mud that

covered the ground, and I had to find a somewhat elevated spot

on the pavement to escape the vile swamp, whose foul-sweet

haze enlightened me about its nature. Around me was a wild

roar and murmur of voices. All the windows were crowded,

and from there cloths were waving to acquaintances on the

street.

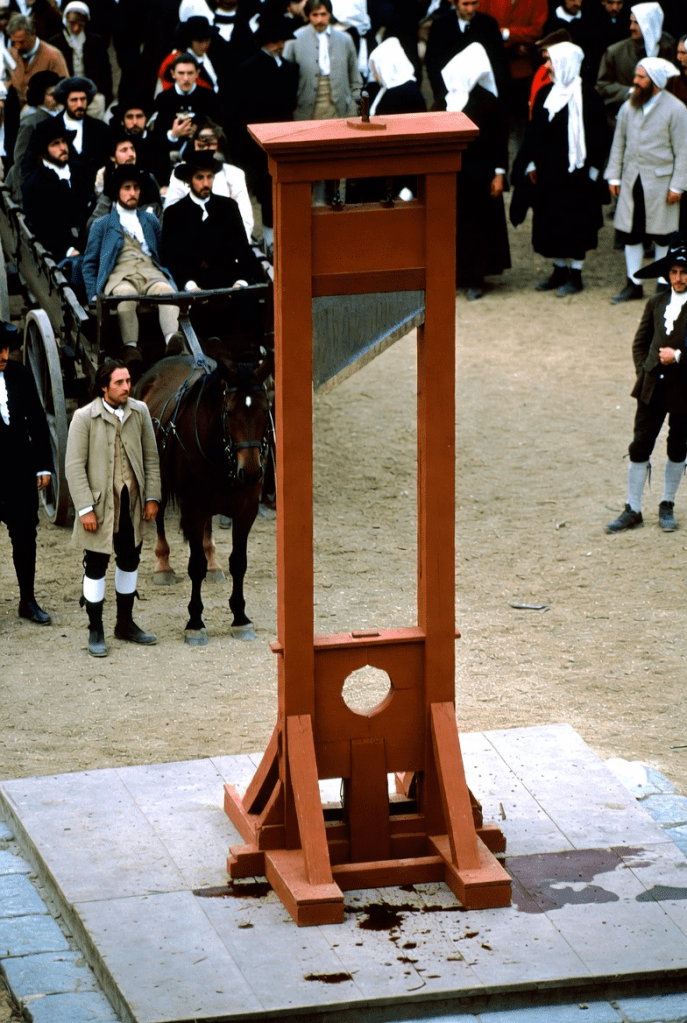

Just in front of me, in the middle of an irregular square,

towering over all the heads, hoods and hats, stood a slim,

reddish-brown, two-footed gallows, on which at the top under

the crossbeam, the drop knife hung slanting and flashing. The

posts, between which it ran, shone dark and greasy in the

daylight, so much was the wood smeared with blood and

human grease. The condemned men rose stiffly and with great

effort from the seat boards of the cart. A horse neighed,

scenting the haze of the square. The poor condemned who had

arrived at their final destination now helped each other politely

and courteously to dismount, the old clergyman made an effort

to help the crippled Doctor Postremo, who was making terrible

faces and chattering with his teeth. I saw the white-powdered

hair of the other and the hunchback’s fuzzy head walking the

narrow alley between the soldiers. The doomed men quietly

and slowly climbed the small staircase up to the blood scaffold.

Abusive words flew at them, fists were shaken, ugly, fat market

women, who stood in the front row, sitting on benches knitting,

were even telling dirty jokes.

I saw exactly every single face and except for Postremo,

who grimaced, they all looked with a stony attitude in face and

gesture towards what was coming. The ring of people around

Guillotine’s machine found itself in grinding motion, and I was

gradually pushed very close, so that the victims stood with

their faces turned toward me. I wished myself far away, to get

rid of the terrible pressure under my heart, with which the sight

of such sad preparations tormented me. But I could not move,

as I was wedged so tightly, I could not even turn my head away

from the tangled hair of an unclean woman who smelled of

garlic, and I had to be sneezed on from behind by a man who

had caught the sniffles. But these small adversities quickly

faded before a nameless horror.

Now a giant swung onto the scaffolding, whose sight

surpassed in meanness everything I had ever seen in my varied

life. On tremendously broad shoulders, over a naked, red-

haired chest and muscular arms rose the face of a devilish

monkey with bared teeth, maliciously glowing eyes and a fiery

comb of red-yellow bristles. Samson, whose portrait I had seen

in a bookstore, it was not. I knew that he was indisposed and

that his first assistant was standing in for him. Horror seized

me at the sight of this guy.

This man-beast, who was followed by two crude-looking

figures grinned, licked his blue lips and then pointed with a flat

thumb at Postremo. The two guys behind him pounced on the

hunchback in an instant, who kicked with his feet, hissed

incomprehensible words and pulled his misshapen head even

deeper into his shoulders. They tied him with lightning speed to

a vertical board, and tipped him over, so that the helpless man

was lying with his chin on a double board, cut out in the shape

of a semicircle, the upper half of which was now pulled down

between the posts and pressed down. A shiver ran through me,

as the red-haired, blood-black hand of the executioner pushed a

protruding knob in the post. The guillotine whistled down.

Something jumped into a basket, the hunched body twisted,

writhing, and flapping its feet, just as poor Bavarian Haymon

did under the murderous ring, and from a huge dark- red

wound, from which a flashing semicircle seemed to hang,

blood gushed out in thick streams, which then gurgled and ran

heavily down the side wall. The executioner’s hand reached

into the basket, lifted the head up high by the stained, white

hair. The axe had not reached the neck, and so the lower jaw

was severed and hung separated with the semicircle of the teeth

on the body, so that I once more saw the mutilated grimace of

the doctor. And this hideous head slowly drew the eyelid over

the right eye, as if he wanted to wink at me.

“It’s not pretty, citizen – but how could he have dressed

up the hunchback angel maker any other way?” said a

craftsman next to me, pulling out a flask from the upper,

opened part of his burn-stained apron smock. “Here, drink once

this will keep the food down if it wants to rise from the

stomach!”

I took a sip of the pungent and burning juniper brandy,

and the trickling warmth inside gave me strength. Once again I

looked around me to see if I could not escape from what was

coming, but it was impossible to squeeze through this wall of

human bodies. A wall was around me that no one could have

penetrated.

So I had to witness the execution of all six condemned,

and each time the leathery clap of the falling knife sounded, I

trembled from my head to my feet. The cold sweat broke out

and my legs trembled violently. The last of the crowd, after the

old lady, who died quietly and without any movement, came

the officer of the Flanders Regiment, who had remained loyal

to the king the longest. He placed himself at the board. While

the executioners nimbly fastened the blood-soaked straps

around his body, he looked at the blood man’s face with eyes

flashing with anger and said loud and clear:

“Do not dare to hold up my head with your paws, red-

bristled pig!”

But the executioner just pursed his bulging lips, waited

for the overturning of the board and the clasping of the neck in

the hole formed by the two semicircles of the double boards,

dropped the axe that the two blood fountains sprang from the

stump of the neck, and reached into the basket.

But immediately, with a grunt of pain, he pulled his hand

out of the basket and flung his index finger rapidly back and

forth in the air, as if he had touched red-hot iron. In a senseless

rage, he kicked the basket several times with his foot, so that

the severed head bounced and jumped in it. Then he hid the

finger of his right hand in his clenched left hand and uttered a

blasphemous curse.

“The aristocrat bit his finger!” The man with the apron

smock shouted. “They are not so easily killed, these haughty

ones!”

Then, as if a bright light shone on me from heaven, I

thought of Isa Bektschi and the parable of the beheaded

evildoer, who used the last of his last strong will with a similar

thought of revenge.

Meanwhile, one of the servants, a jaunty black man,

jumped up to the basket, looked inside, at which the bystanders

had to laugh, and, grasping his hair with two fingers, lifted his

head out. The eyes of the dead man looked half-closed,

contemptuously staring at the gawking crowd, and a thin red

stripe ran down his chin.

Cursing, the redhead climbed down from the scaffold.

In the depths of my soul, I understood the effort of the

priest, perhaps not entirely comprehensible to himself,

although he eagerly displayed it, with which he exhorted the

dying to focus all their thoughts only on eternal bliss,

repentance of sins, and the continuation of life in God, and to

do away with all thoughts of revenge and earthly desires. What

immeasurable wisdom lay hidden in this need, what promise

and what consolation! An indescribably joyful knowledge

glowed through me when I thought of such things and I almost

regretted that my own path had not ended here.

Now that there was nothing more to see, the crowd

loosened and flowed away, getting lost in the side streets. The

windows closed, and the two helpers appeared with water and a

cart on which they loaded the dead remains of the executed in a

crude manner.

I still stood spellbound in my thoughts of Isa Bektschi’s

words, which he spoke to me, when I lay ill in the haunted

room at Krottenriede, when I felt that someone was looking at

me.

When I turned quickly, my eyes met those of a still

young man with a brownish face of regular cut and dark eyes,

from which an extraordinary willpower flashed at me. A great

power emanated from this gaze, with the strange, austere

beauty of the face and the harsh mouth that harmonized.

Gaia’s Master Frequencies

Posted in Uncategorized on January 15, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 220- 224

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, fantasy, fiction, life, writing on January 15, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

Among the otherwise light-hearted and good-natured

people were mingled at that time riffraff and tavern scavengers,

who were only interested to fill their coffers, to drink, to

fornicate, to whore, to splurge and to murder. Also even among

the leaders, many of whom meant well, they were swamped by

those who would use any means and who stirred up the

common instincts of the crowd in order to make himself

popular with the plebs. A gentleman of my standing would be

better in the safety of home, instead of traveling in a country

where there is neither discipline nor justice nor security. I

would soon see that a limited measure of freedom is like a

fortifying drink of good wine, but a mad exuberance like the

exuberance, however, as it reigns here, is like senseless

intoxication and insanity.

This kind of expression in a mail coach driver surprised

me; however, his expression and posture told me that he

belonged to the educated classes. And so I addressed the

question to him, how it comes that a man of such politesse

could not find any other position than that of a stagecoach

driver.

The coach driver smiled and said:

“Don’t bother addressing me as a gentleman! During this

time I am quite modest and observe as a philosopher that which

I cannot prevent. Who in such times holds his head too high

can easily lose it, and since I only have this one, I am worried

about it and on my guard. – Forgive me, mein Herr, but the road

is getting so bad that I must turn my attention to it.”

With these words he turned and seemed to pay attention

only to his reins and the trotting of the horses. But already the

nonchalant posture of the reins, indicating great practice and

the noble certainty of his movements told me, from which

social class my coach driver came from.

In front of a town, which we were approaching, we were

stopped by a strong group of armed peasants, who, they

claimed, had been assigned to guard the road. One of them

grabbed the reins of the horses, which were walking at a walk,

while two of them, with their muskets extended, stepped up to

the coach.

But the coach driver, about whose fine and educated

nature, I had just voiced my thoughts to, spat in a vulgar

manner into his hands and shouted in the lowest dialect of the

area:

“You dung-scratchers and filthy beetles, you lice-pack

want to dare to stop a citizen commissar? Death over my life, if

I don’t bring you under Doctor Guillotine’s machine, you

thieves and skunks! Away, by the fiery claws of the devil, or I

shall ask the citizen commissar in the coach to write your

names in his pocket-book!”

Immediately they drew back, pulled off their greasy hats

and shouted:

“Long live freedom!”

Our coach rolled on. The driver laughed to himself.

“What did you say about the machine of Doctor

Guillotine?” I asked him.

“Ah – have you heard nothing of it? Imagine that they put

you on a board between two beams. High above hangs a knife

with a slanting edge, which falls and separates the head so

neatly from the trunk as if it were only a head of cabbage on a

thin stalk. It travels around the country, the machine of Father

Guillotine.”

In my mouth was suddenly a tepid, sweetish taste, which

almost made me sick. It was the air in this country that I had in

my mouth. It tasted like blood. And with a second-long freeze I

thought of the words of Demoiselle Köckering, her shrill cry–

“A knife hangs – falls -‘”

In the city, whose gate lay before us, a bell began to ring

low and menacingly: Death-Death-Death-Death.

My fear vanished as quickly as it had come.

“Non omnis moriar,” I said to myself.

“I will not die completely!”

I was standing under the archway of the Paris house

where I lived and looked down the street.

Muffled sounds came closer. Whistles, shrill laughter.

A bunch of soldiers in various uniforms, red and white

striped, dirty trousers on their legs, crushed hats with the new

cockades on the long hair, came down the street with

shouldered rifles. Two barefoot ragamuffin boys ran forward as

drummers. On one of the two drums I recognized the scratched,

colorful coat of arms of the Esterhäzy regiment.

Behind the soldiers ran a large crowd of people, girls,

men, women and children. Among the people one saw ragged

prostitutes, fellows with murderous clubs, tramps, and lowly

rabble. In the middle of this throng swayed and bumped a high-

wheeled cart on which six people were sitting. The first one my

eyes fell on–

Merciful God!

The cart stopped because the procession was stalled, and

I looked closely.

The first one I caught sight of was Doctor Postremo.

A shiver of fever shook me.

He was sitting in front, with his hands tied behind his

back. His now snow-white ugly ape-head with coal-black thick

brows and whiskers sat deep in his shoulders.

His eyes were filled with mortal fear, and his broad

mouth stood wide open.

Doctor Postremo!

“Samson won’t be able to cope with that hunchback!”

The crowd shrieked with laughter.

“They will have to pull out the pumpkin for that one!”

answered a second. “Hey, old man? Don’t you think so, turtle?”

Postremo made a ghastly face, closed his mouth,

gratingly moved his jaws, and then spat in the face of the man

who had addressed him.

A burst of laughter flew up.

“Bravo! Good aim, hump!”

Two soldiers pushed back the angry man, who, with his

disgusting face covered in spit, wanted to get on the cart. Next

to the Italian sat an old, venerable cleric in a torn cassock,

behind him was a stern-looking man in a blue silk jacket

embroidered with dull silver, and a gaunt lady who moved her

lips in prayer. The last seat on the cart was taken by a former

officer from the Flanders regiment and a young man, smiling

indifferently and contemptuously in a morning suit. The officer

bit his lips angrily and said something to his neighbor, who

answered with a shrug of the shoulders.

Immediately the cart started to move, rumbling and

skidding into motion, and the crowd sang a wild song unknown

to me, that roared down the alley. The soldiers put their short

pipe stubs on their big hats and sang along enthusiastically.

Without will, driven forward by an irresistible force, I

stepped into the middle of the crowd behind the executioner’s

cart on which sat the wretch who had robbed me of the

happiness of my poor miserable life with his satanic arts.

Nevertheless, I felt no resentment against him, as much as his

look reminded me of the greatest pain that I had ever suffered.

But now I felt as if he had only been the tool of an inscrutable

power which had directed everything as it had come. It also

seemed to me that the terrible end to which he was now rolling

toward on the shaking seat of the cart was not in the light of a

punishment that had been executed on him, but as a redemption

for this poor, wicked spirit, bound in a misshapen body.

Between these more foreboding than clear thoughts, was the

inexplicable feeling that moved all the people here, the terrible

and unfathomable desire to witness a terrible operation on

others, which in this time of great death and uncertainty of all

fate, excited great interest because without a doubt many of

those who today walked along freely and safely might in the

very near future experience the same.

In these minutes, the revolution, which I had longed to

see close up, was seen as something unspeakably horrible and

terrible. It was as if one had unleashed vicious animals against

sentient human beings, creatures of the lowest kind, which

cannot get enough pleasure in the suffering of their fellow

beings, as if demons from the depths had united, to eradicate

their former tamers and rulers and with them to exterminate

every order. What I saw in the reddened, eye-twinkling,

distorted faces around me was not humanity. Then I saw the

young nobleman and the officer on the rearmost seat, but also

from these victims a cold wave flowed toward me. They were

evil in their hearts to the last. It was obvious that to them the

people in the street were the same as the cobblestones, the dirt

that stuck to the high wheels of the cart, or the half-starved dog

that yelped and jumped around the harnessed mares.

In my desolate misery and in the burning pity that almost

burst my heart; I nevertheless knew clearly that in the last

feelings of these two on the cart lay all their guilt. They had

despised all people, God’s creatures as well as they, all their

lives and still despised them in their own bitter hour of death,

because they were unclean, uneducated, sweaty and lousy.

These nobles did not consider that their own insensitivity had

made of them what they were: a horde of half-animals, who

had to defend themselves against the cruel scourge of poverty

and being outcasts.