Chapter 1. In the shadows of Gaia’s fringe, Elara lives a quiet life – until something ancient begins to speak through her dreams. This is a 12 chapter series that will be posted weekly.

Archive for January, 2026

Sparks of the Eternal Oak

Posted in Uncategorized on January 31, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 285- 287

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, fantasy, fiction, short-story, writing on January 28, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

I walked around the building. No, it had no second exit.

Nowhere. I looked once more at the flat, red bricks of the

entrance, hollowed out by feet, over which Sennon had stepped

for the last time.

In the afternoon I took an interpreter with me, a young

and clever Spaniard, and went to see the Sheikh of the Halveti,

Achmed. I was immediately admitted and had a drink of coffee

with him and a young serious-looking dervish, on a colorful

tray in a bright room. The Spaniard told the Sheikh what I said

to him.

No, the Sotnie (Herr) had come for nothing. It was well

known that a soldier of Austria entered the Tekkeh and never

came out again. However, this must be a mistake, because the

Tekkeh has only one door.

Yes, fine. But how to explain the thing? Who was the

dervish in the brown robe, with the turban of the Halveti and

the amber necklace?

Oh, if only I had known the life of Melchior Dronte! If I

had known about Isa Bektschi! But at that time the sheets with

Vorauf’s transcription were lying in my house thousands and

thousands of miles away from Schipnie, on the country road

with the poplar trees, sealed and wrapped, not even visible to

the moon when it looked through the window of my room at

night.

Yes, the dervish? It had been none of them. Moreover,

the door of the Tekkeh was always locked- with three old locks,

each of which weighed close to two pounds; very old locks

from the days of the Sultans.

But some explanation – must there be some explanation?

How did Vorauf and the monk get through the locked door?

The sheikh with the white beard and the young dervish

looked at each other, glanced at me and the interpreter with a

look of polite disdain; yes – I was used to such looks, since I

had gotten to know Mohammedans, and then they spoke

quickly and quietly with each other. I understood only the

words “syrr” and “Dejishtirme!”

The old man bowed to me. He was very sorry that he was

not able to help me. Unfortunately nothing more was known.

No, unfortunately, nothing is known, agreed the dervish.

The interpreter translated. We were looked at amiably and

inquiringly. The eyes said, “May we now ask to be alone again,

my curious Herrn?”

I stood up. There was nothing more to be learned. I could

see that. The dervishes were very polite. The sheikh touched

the carpet with his hand before he brought it to his forehead

and mouth.

“What were they talking about?”

I asked the Spaniard as we stood in the blinding sunlight

under the cypress trees and listened to the laughter and

gurgling of the wild pigeons above us. The interpreter shrugged

sheepishly.

“They not talk like Shiptar, Albanian, Sotnie,” he said.

“They speak very softly. I did not understand. It was Osmanli,

turc, mon capitaine, you understand – -.”

“What do the words ‘syrr’ and ‘Dejischtirme,’ mean?” I

asked.

I had remembered them well from memory.

The interpreter shook his head, then he said:

” ‘Syrr!’ It is secret, yes, and ‘Dejischtirme’, says in

German: an exchange.”

“Yes, and what does it mean?”

“Le mystere – the secret of the transformation–a

transformation in a living body -. vous comprenez?”

“Fairy tale! Fairy tale!”

Yes, here time had stopped. In the coffeehouses, and

when it got dark, the Turks only went out in twos and threes, so

afraid were they of the jinns, the Afrits and the Gulen.

But I, Doctor Kaspar Hedrich – —

Transformation. So the good Sennon Vorauf. What had

he said? What did it say in Riemei’s letter?

“I am called!”

Then, in my distress, I went once again to the

Headquarters.

“Cheeky swindle!” shouted Herr Lt. Switschko. “The

fellow deserted. The Turks were in on it with him. I have seen

it myself, how they bowed down to the ground before him, and

the women came to him with sick children. I should not have

tolerated the story from the beginning. Would you like to come

with me to the Menashe, Herr Regimental Surgeon?”

No, I did not go. I also didn’t want to see Riemeis and

Corporal Maierl. I was very sad. Oh, these precious leaves in

front of me! Why did these leaves have to fall into my hand so

late? But he had wanted it that way, Sennon, the – yes, the Ewli.

I am sitting here all alone, and it is midnight. All that is

long gone, life is short, and what I have missed will not return.

What wanderings are in store for me, what paths?

“Syrr,” sighs the wind in the poplars. “Syrr!”

Mystery!

End.

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 280- 284

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, family, fiction, life, writing on January 27, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

This was all the easier for me because many of our

classmates thought that Sennon, for all his affection, was a

little disturbed. But nevertheless, they all liked him, and I know

of no instance of anyone teasing him, arguing with him, or

holding his peculiarities against him, as children are wont to do.

Even the crudest of us knew that he deserved love and

consideration, for he was the kindest and most helpful person

even in his youth. Every occasion to do good to others was

welcome to him. Even if it was only the small sorrow about a

bad grade that he had received – Sennon would not rest until he

had made the afflicted person cheerful again with his loving

consolation. I myself was very attached to him, and when he

rebuked me in his gentle way, it had more effect on me than if

it had come from my own good father.

Yes, now in this spring midnight, when the wind passes

over my roof and invisible feet seem to walk along the street,

ever onward, toward an unreachable goal, everything that was

lost in the whirlpool of the young years and in the lost, terrible,

unfruitful time of this insane war sinks to the bottom of the

soul. I remembered the summer day when, to my amazement, I

saw the songbirds in the meadow on the head and shoulders of

the resting Sennon and a little weasel was sniffing at his hands.

A weasel! The shyest of all animals! And how everything

disappeared when I stepped up to him. I also remember how

Sennon helped a sick drunkard, the Pomeranian-Marie, who,

seized by severe nausea, fell to the floor with a blue face. He

picked her up, and stroked her forehead softly with his hand,

whereupon she smiled at him and continued on her way,

completely recovered. Like I was there, when blood was

spurting out of a sickle cut and it stopped when he stepped up

to it, and how the flames on the roof of the carpenter’s roof

shrank, twitched and went out, as Sennon appeared and

reached out his hand. I saw it with my own eyes. How could I

have held all this in such low regard that I forgot it? How sorry,

how unspeakably sorry I am for the years I spent so dully

beside him. I would give all my exact science to do it over.

No, I cannot approach the matter with emotional regret.

I was foolish – like all young people. When I came home

for vacations, I found that contact with the worker in Deier and

Frisch’s optical workshop was not appropriate. I preferred to go

with Herr Baron Anclever from the District Headquarters and

the dragoon lieutenant Herr Leritsch.

I cannot change it. It was like that.

But then I came to my senses. Herr Professor Schedler’s

lectures about psychic phenomena were the ones that pulled me

out of the silly life I had fallen into. I began to look into the

depths, into the twilight abyss, diving into which held a greater

incentive than chasing after little dancers, drinking sparkling

wine and conferring with morons about neck ties, pants cuts,

and race reports. I threw them out of my inner life, as one

removes useless junk from a room in which one wants to settle

into. But I also forgot about Sennon.

Oh, what have I lost! I put my cheek on the last leaf of

writing on which his hand rested in farewell. I call his name

and look at the black window panes in the nonsensical hope

that his dear, serious and yet so joyful face may appear behind

the glass instead of the darkness outside. Everything that I now

long for so unspeakably, was close to me, so close! I only had

to reach out my hand, just to ask. Nobody gives me an answer

now, and all my knowledge fails me. Or shall I console myself

with the vague excuse that Sennon Vorauf had a so-called “split

consciousness” and that the Ewli of Melchior Dronte could be

nothing else than an allegorical revival of the sub

consciousness, that became the second ego of Vorauf?

No, I can’t reassure myself with the manual language of

science. For I am mistaken about all of it —

When I came to Albania, occupied by us, in the course of

the war and went from Lesch to Tirana, in order to establish a

home in that cool city, with its ice-cold, shooting mountain

waters at the foot of the immense mountain wall of the Berat,

for my poor malaria convalescents, I saw Sennon Vorauf for

the last time. It was exactly that day that a searchlight crew had

just returned from Durazzo via the Shjak bazar. Among the

crew members that were searching for their quarters I

recognized Sennon.

I immediately approached him and spoke to him. His

smile passed over me like sunshine from the land of youth. He

was tanned and erect, but otherwise looked completely

unchanged. I did not notice a single wrinkle in his masculine,

even face. This smoothness seemed very strange and unusual to

me. For in the faces of all the others who had to wage war in

this horrible country, showed misery, hunger, struggles and

horrors of all kinds, and everyone looked tired and aged.

We greeted each other warmly and talked of old days.

But time was short. I had meetings and many worries about the

barracks, for the construction of which everything that was

necessary was missing. Our ships were torpedoed; nothing

could be brought in by land. Everything had to be brought in

from Lovcen, floated across Lake Scutari, and then from

Scutari brought overland in indescribable ways. Every little

thing. And boards were no small matter. I negotiated with

people whose brains were made up of regulations and fee

schedules. It was bleak; I felt like I was covered in paste and

old pulp dust. All this disturbed me. I promised Sennon I would

see him soon. He smiled and shook my hand. Oh, he knew so

surely—-!

In the afternoon a man from his department, Herr

Leopold Riemeis, came to me and had himself examined. He

had survived the Papatatschi fever but was still very weak. I

involuntarily asked him about his comrade Herr Sennon Vorauf.

His face was radiant. Yes, Herr Sennon Vorauf! He had saved

his life. A colleague, I thought and smiled. He had naturally of

course also, as I did at the time, taken a fever dream for truth.

But I was curious, gave Riemeis a cigarette and let him tell the

story.

Riemeis was a Styrian, a farmer’s son. Sluggish in

expression, but one understood him quite well. It had happened

like this: In a small town, in Kakaritschi, he, Riemeis, had been

struck down by fever. But it was already hellish. He was

burned alive, his skin was full of ulcers, and on other days he

would have liked to crawl into the campfire because of chills.

And there was no medicine left. The senior physician they had

with them shook his head. In eight days Riemeis was a skinned

skeleton, and not even quinine was left, it had long since been

eaten up.

“Go, people!” The senior physician addressed the platoon.

“If any of you has quinine with you, he should give it to

Riemeis, maybe the fever will go down, or we’ll have to bury

him in a few days.”

They would have gladly given it away, but if there is

none left, there is none left. My God, and there were already

crosses on all the roads of the cursed land, under which our

poor soldiers lay – in the foreign, poisoned earth.

“There you go, Riemeis -” said the doctor and patted him

on the shoulder. “There’s nothing that can be done.” And left.

Riemeis had a burning head that day, but he understood the

doctor quite well, “There’s just nothing that can be done.”

Sennon was sitting next to Riemeis’ bed. It was at night.

“Sennon, a water, I beg you!” moaned the sick man.

But Sennon gave no answer. He sat with his eyes wide

open and did not hear. Riemeis looked at him fearfully. And

then it happened. Something glittering fell from the forehead of

Sennon and hit the clay floor. And then Sennon moved, looked

around, smiled at his comrade, bent down and picked up a

round bottle, in which were small, white tablets. Quinine

tablets. A lot of them. From the depot in Cattaro.

Our peasants are strange. They didn’t say anything to the

doctor, but they put their heads together and whispered.

“My grandfather told -“.

They did not question Sennon about it. They were shy.

But they surrounded him with love and reverence, took

everything from him, did all the work for him, and listened to

his every word. And they understood well that it was precisely

on his heart that all the suffering of the poor lay, who were

driven into this killing, without even being considered worthy

of questioning. This is not an accusation. Our country was in

danger. Even those in power over there did not ask anyone.

How else could they have waged war? How could they take

revenge on us because we were more efficient and industrious?

But why do I speak of these things! It will take a long time

until mankind will be able to judge justly again. So Sennon

Vorauf.

He bore the woe of the earth, all the misery of countless

people, and his heart wept day and night. Even though he

smiled. They understood well, his comrades, and it would not

have been advisable for anyone to approach Vorauf. Not even a

general. The people had gone wild through their terrible

handiwork. But there was no opportunity. Never has there been

a more well-behaved, more dutiful man than Vorauf, but they

all thought that shooting at people – no, no one could have

made him do that. Riemeis said.

Oh, I had to go and mark out the ground for the barracks.

I asked Riemeis to give Sennon my best regards. I would come

tomorrow. Yes, tomorrow! Already that evening I had to leave

for Elbassan.

Then came the letter from Riemeis to me and a copy of

the desertion notice.

But fourteen days passed before I could leave for Tirana.

A full fourteen days. I hoped that Vorauf would have been

found after all.

First I visited the commander of Vorauf’s department,

who had filed the complaint, Herr Lieutenant Wenceslas

Switschko. I found a fat, limited, complacent man with

commissarial views, for whom the case was clear. Vorauf, a so-

called “intelligent idiot”, had deserted, and the Tekkeh he had

disappeared into certainly had a second exit. One already

knows the hoax. But, woe betide if he were brought in! Well, I

gave up and went to the people. Riemeis received me with tears

in his eyes. Corporal Maierl, too, a good-natured giant, a

blacksmith by trade, had to swallow a few times before he

could speak. They recounted essentially what was written in

Riemei’s letter to me. We went to the Tekkeh of the Halveti

dervishes. Slate-blue doves cooed in the ancient cypresses. A

rustling stream of narrow water rushed past the wooden house

and the snow covered crests of the Berat Mountains shone

snow-white high above the pink blossoming almond trees and

soft green cork oaks. In the open vestibule of the Tekkeh stood

large coffins with gabled roofs, covered with emerald green

cloths. On each of them lay the turban of the person who had

been laid to rest.

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 275- 279

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged faith, family, fiction, life, writing on January 26, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

It took a very long time until I recovered from the intense

pain that hit me at the renewed new loss and to regain my

equilibrium.

Soon after this incident, my father fell ill and died,

occupied to his last breath with the care for my and my

mother’s further life. A few weeks later, my mother caught a

severe cold, which turned into a severe pneumonia. I held her

hand in mine until her last breath and had the consolation of

hearing from her mouth shortly before her death, a saying that

was well known to me:

“Thank God, we will meet again!”

Nevertheless, I cried bitter tears because she had left me.

I had long since been offered a well-paid position in the

institution and my modest needs were amply provided for.

In my free time, after careful consideration, I wrote the

long story of my life as Melchior Dronte and this brief

description of the hitherto peaceful existence that I led under

the name of Sennon Vorauf, and provided the whole with a

preface. I now pack and seal the described sheets and will mark

them with the name of Kaspar Hedrich who in the meantime

has completed his studies and, like his late father, has become a

doctor.

He lives in a nearby town, and when the right time has

come, this completed manuscript will perhaps give him an

explanation of my being, and it may be that it will put death in

a different and less gloomy light for him and others than it may

have appeared to them so far.

Some thoughts, which are difficult to put into words, of

whose comforting truth I have convinced myself, cannot be

shared with anyone. Everyone must find them in his own way,

to the beginning of which I believe I have led everyone who

seriously and devotedly strives to explore the truth.

It was about time that I did it. For great misfortune is in

store for those who are now living —.

To the Imperial and Royal Palace – Command Center

in Tirana.

The charge of desertion is filed against the infantryman

Sennon Vorauf, assigned to Searchlight Division No. 128/ B for

unauthorized absence from his post.

Herr Wenzel Switschko, First Lieutenant.

Herrn Wolgeborn regimental physician Dr. Kaspar

Hedrich

Field post 1128

Dear Herr Regimental Doctor! I regret to inform you that

a report has been made to the Royal Headquarters that our

friend Sennon Vorauf has deserted. Dear Herr Regimental

Doctor it is not true that he deserted, but it was like this. I and

Vorauf and Corporal Maierl went for a walk in the Albanian

town of Tiranna, and Vorauf had been acting very funny

already the entire day and all of a sudden I was scared when he

said:

“Thank God we will meet again.”

He was very kind to us and he gave his silver watch to

Maierl and gave me a ring with a red stone.

“Keep this for a souvenir,” he said, and so I said,

“Sennon, what are you doing?”

Meanwhile we went to a Tekkeh of the Halveti dervishes,

this one was a wooden house where there were coffins of holy

Muhamedan Dervishes with green cloth on them by the door

and Vorauf said: “I am called,” and went inside.

Then the corporal said, “Vorauf, how dare you! It is

strictly forbidden for soldiers to enter the sacred places of the

Muhamedans, but he went in, so we waited for him and after a

while a dervish came out with a black turban and a small beard,

a handsome man and he had a brown robe and a rosary with a

yellow beads around his neck and this dervish gave us a

friendly greeting, it was strange and we saluted him and again

we waited for a long time, but no one came. So I went to the

house where the dervishes live and in the meantime Herr

Corporal Maierl stayed at the Tekkeh to watch, so one of the

dervishes with a grey beard went along with me to the Tekkeh

and searched for Sennon. Then he returned and said there was

no one inside, so we looked at each other, went home and the

corporal reported to the commander Herr Lieutenant

Shwitschko and then he cried with me about Sennon and today

it’s been five days and there is no Sennon to be found, so only

our Lord knows where he is, and the regimental doctor knows

that he was a dear friend, and you might not know Maierl says

he was a holy man, he did so much good for all of us and gave

away his things. I wanted to report this, and if the Herr

regimental doctor wanted to come it is a whole riddle with

Sennon and I greet you obediently,

Herr Leopold Riemeis. Infantryman, searchlight

128/B.

It is around midnight.

Below my windows the country road runs out into the

flat countryside, endless, gray. The wind rustles in the poplars.

It picks at my windowpanes. Ghost fingers, huh? No, it’s just

the old leaves, which held out so splendidly in the freezing

winter storms and which now the damp wind picks off, one by

one. Down with them! Should one think it possible that I, Dr.

Kaspar Hedrich, a man of exact science, the author of the book

“The so-called occult phenomena. A Completion”, yet here I sit,

a beaten man.

Must I now recant, or what should I begin? Did I see as a

boy of fourteen sharper and better than I do now?

I must go back. I have to get rid of the thick sheets of

paper that my boyhood friend, Sennon Vorauf, left with his

strange, squiggly handwriting, with a pale blue ink, as if the

whole thing were a bundle of letters or diary pages from the

eighteenth century. Did he do this on purpose? It does not

correspond at all with his straight and sincere nature. If ever a

man was honest with himself and others, if anyone was

passionate about the truth, it was Sennon Vorauf. For that I will

put my hand in the fire.

After the horrible war, after all the misfortunes, the

stupidity and hatred that have been brought to my country, I

have returned home. And the first thing I find is this thick, now

unsealed and read pack of closely written pages, which was left

with me while I was with malaria patients in Alessio or Lesch,

as the Shiptars call it, a poisonous and sad summer and was

summoned to Tirana by a soldier’s letter to look for Sennon.

But I have to go back; I have to look at things from the

beginning. Maybe Sennon is looking over my shoulder or is

looking, even invisibly, in at the window. Who can know?

We were together a lot in childhood. In his writings, he

mentions the mysterious incident that took place on the river

journey and in which he saved my life. Also my father, who

had lived in the Orient for a long time, also believed it. He told

me so himself. Only I, I told myself later that a rapid onset of a

cold fever after I had rescued myself from the water-hole had

fooled myself into believing that he had saved me.

And what happened later? I once went very early in the

morning to pick up Sennon according to my habit. He was still

in bed, his mother told me to go in and wake him up. I entered.

Sennon was lying on his back in bed with his eyes open and

staring. His chest did not rise and fall. I saw, already at that

time with the observation of a doctor and practiced it

unconsciously, that his breathing had stopped. I became restless

and put my hand on my friend’s chest. His heart stood still.

Fear gripped me. Was I supposed to go to Frau Vorauf in

despair with the terrible news that her son, to whom she had

been attached with an uncommonly tender love, was lying dead

in bed? Thick tears dripped from my eyes, and I could not take

my eyes off the calm and stylish face of my dearest playmate.

Then it was as if I looked into the fine red mark that Sennon

wore like an Indian caste badge between the curved brows, a

luminous mist seemed to come out of the air and only became

denser as it neared him. But this lasted only a very short time,

and while I was still stunned with amazement at the bedside,

life came back into the rapt look of my friend, his eyes moved,

his usual sweet smile (never have I seen a person smile so

enchantingly as him), played around his lips and as if

awakened he said, “Is it you, Kaspar?”

In the manner of a boy, I immediately informed him of

my just made perceptions and added that I had been on the

point of either calling his mother in or to call him back to life

by shaking him and pouring cold water on him. Then he looked

at me seriously and asked me that if I should ever find him in

such a state again, not to call him to life by force and to prevent

the attempts of others in this regard.

“It is worse than what is called dying, when the thin cord

between soul and body is torn. It is a pain which nothing can

compare to,” he said sternly, and nodded to himself.

I was used to incomprehensible speeches from him. He

often muttered names to himself, the meaning of which was

quite incomprehensible to me, named people with whom he

could not possibly have come into contact with. But I was a

boy, didn’t think much about such things, and thought to myself:

“Today he’s crazy again, that Sennon!”

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 270- 274

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, family, fiction, life, writing on January 25, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

I suddenly saw differently, more unclearly, with physical

eyes. My mother was standing in front of me, shaking my arm

violently and shouting.

“For God’s sake! Child, wake up! Wake up!”

I was sitting on the stove bench, so terribly frightened

and breathless that my heart almost stopped. My mother told

me then that she had seen me looking up at random with open,

unmoving eyes. She had asked me what was wrong with me,

and when I did not answer, she went to me worriedly. But

despite the initial gentle touching and then more and more

violent shaking, I sat there as if completely dead, without

breath or any other sign of life, until I finally to her

unspeakable joy came out of the deep faint and back to my

senses.

After half an hour, however, our neighbor, the doctor,

came to thank me for having saved Kaspar’s life with so much

courage and determination. Kaspar had come home wet and

completely frozen to death and had told that he had fallen in on

the arm of the river and had been close to death from

exhaustion. In his fear he had without thinking that this must be

in vain, called my name several times. There I was, who had

probably returned to my usual favorite place, and suddenly

stepped out of the bank of willows, went straight to him, and

with a jerk of incomprehensible strength pulled him from the

wet and cold grave and thus saved him. But when he wanted to

thank me, I was suddenly no longer there and despite all calling

and searching remained untraceable. And then Kaspar,

completely frozen and stiff, ran home, where he, filled with hot

tea, was lying under three feather bed covers and sweating.

It now came to a friendly meeting that ended with mutual

astonishment on both sides, friendly contradiction between my

mother and doctor Hedrich, with my mother pointing out that

she had not left the room for a moment, whereas the doctor

pointed out the specific manner in which Kaspar had recounted

his experience. But when my mother, continuing her

description, spoke of the inexplicable condition into which I

had, however, fallen at the time when the accident happened,

the doctor looked at me with a peculiar look and said:

“Well, well, were you in the end -? But no! Kaspar may

have brought home a little fever, and there the boundaries

between dream and experience disappear!”

With that, after a friendly goodbye, he went out of the

parlor. But then he poked his head once more through the door,

looked at me and said:

“Nevertheless, I thank you, Sennon, and ask you from the

bottom of my heart to continue to watch over my Kaspar, for

you seem to me a good watchman, a Bektschi, as the Turks

say!”

This word, the meaning of which was not obvious to me

at the time, nevertheless put me in the most violent excitement,

and my mother, who must have probably attributed this to the

rising fever, avoided telling my father, who was returning home,

about the incident, probably mainly in order to spare me

questions and thus to spare me new aggravations. It was only

some time after this mysterious event that she told me that a

certain apparition on my body at that time had filled her with

indescribable horror. The narrow scar, which I had as a

congenital birthmark between the eyebrows, just above the root

of my nose, had been visible to her during the unconsciousness

from which she awakened me by force, when a flickering blue

light that looked like the sparks that Kaspar and I let jump out

of a Leyden jar, and this glow went out instantly, when she

shook me hard, but flickered up again more weakly after I

awoke to life, and then gradually faded away. It seemed to her,

she said to me, as if that with the extinguishing of this magical

light my death had occurred, and the thought had shot through

her that perhaps her frightened intervention had suddenly

become fatal to me. Fortunately, I then returned to life.

Later, we avoided talking about the experience any

further, and I believe that she never spoke of it to my father.

But I was so preoccupied with the wonderful ability that had

been revealed to me that it was many nights before I was free

from the recurring dream. Today, on the other hand, I know,

since I have become fully aware of everything, I know that

during those nights, without full consciousness, but also not

completely unconsciously, I left my body and undertook

wanderings, the results of which are too unimportant to be

worth mentioning here.

In any case, the discovery of this power, which I had at

my disposal, brought my thoughts on other and bolder paths

than before, and it was this that was of greatest use to me on

the arduous path to true knowledge.

My and Kaspar’s paths soon diverged to the extent that

insofar as he continued to attend the Gymnasium, while I, at

my father’s request, went to the optic workshop. Because my

parents were poor and reckoned that I, too, would gradually

contribute to the household with love. I was in agreement with

their plan and left secondary school without a moment’s

hesitation.

The fine, great skill and later not insignificant

mathematical knowledge gave me great pleasure. Soon I had

the opportunity during free hours to immerse myself in the

wonderful world of the microscope, and under the guidance of

my father, whose scientific education, despite his modesty, I

began to make all kinds of preparations,

I learned how to color almost invisible cell nuclei and

make them clearly visible, and studied the enigmatic behavior

of the tiniest living creatures, with algae, mosses and molds,

and daily discovered new, wonderful relationships, which

perhaps would have escaped the attention of real scholars, as a

result of their methodical, strictly goal-oriented way of

working.

Thus I was happy in my work and in the security of my

domestic life as only a human being could be. Really there

were little annoyances with young people of my age who did

not want to understand or even considered it disrespectful that I

preferred to stay away from their pleasures and above all

showed no desire for the company of girls, which almost

completely dominated the lives of my comrades. However, I

always succeeded in making them understand in a friendly

manner that the work on my education was above all else and

that the time would probably come later for me too when I

could be accepted into their carefree circle with pleasure.

Gradually I got the reputation of being a strange and

solitary person but I managed to get people to not care much

about me and let me go my own way. My parents, especially

my father, would certainly have preferred it if I had not

separated myself too much from my comrades. But

nevertheless they left me a free hand in such matters and

surrounded me with unchanged and tender love. I suffered

from the fact that I had to be different by nature from my

companions of the same age. But it was precisely in those years

that the insight into the wild adventures of my expired life, as

Melchior Dronte became perfectly clear to me, and the terrible

knowledge about things of eternity worked so powerfully on

me that I urgently needed the solitude, in order to cope with the

impressions that weighed heavy on me.

How I would have liked to have had some person with

whom I could have talked about the survival of consciousness

after the destruction of the body! It would have been a great

relief for me to be understood in the crushing abundance of

contrary views. But with whom would I have been able to

share such unheard-of experiences, perhaps to be attributed to a

diseased imagination, between sleep and waking, death and life?

Perhaps, my mother, insofar as the horror of hearing these

things would have allowed her, with the unfathomable

foreboding of women to have come closer to me emotionally.

But words would have been in vain here, too. So I remained

alone for myself and had to endure the dark agony, of

experiencing once more the events of a past time, and go so

deeply into the night, until everything appeared in the smallest

details as the sharpest memory and gradually blended into the

overall picture that gradually emerged.

How could I have liked the women and girls of the city

whom I knew, since there was only one thing that disturbed the

peace of my soul: the longing for that woman who was

deceptively always disappearing in the double figure of Aglaja

and Zephyrine, and also the only one that could bring

fulfillment to my present life?

And the only punishment that could punish me for the

transgressions of Melchior Dronte, or for my own

transgressions, was the tormenting search, the burning desire

for the face I loved above all else, the brief reunion and the

recent slipping away of this being, to whom I was drawn with

frantic longing.

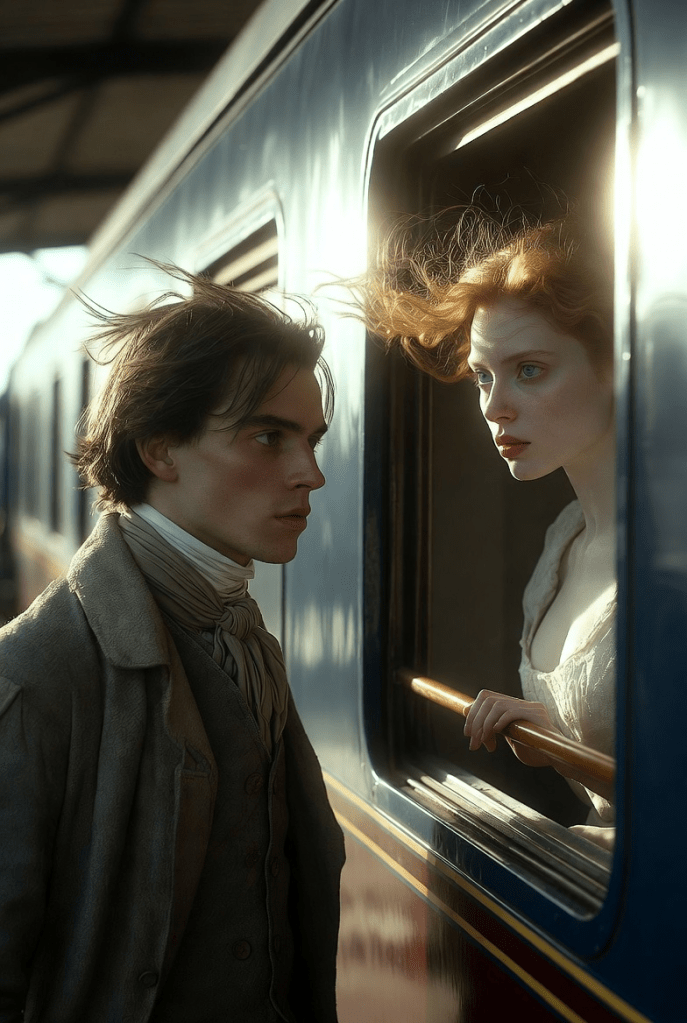

On my eighteenth birthday this happened to me: I had,

yielding to long insistence, arranged a Sunday excursion, with

two friends, to which Kaspar also belonged, which made a

small train journey necessary. We stood at the station in the

early morning of that day, to await the preparations of the local

train, consisting of smaller and older cars, when, with a

thunderous pounding, a long-distance train passed through the

station at a moderate speed.

I was standing at the very front of the ramp and could see

the faces looking out of the broad window frames of the

distinguished train. Most of them were strangers who had

come from far away and were heading for the large port city on

the still distant seacoast, in order to take ships to foreign parts

of the world, especially to the United States.

Suddenly, it was as if a bright glow appeared and turned

everything around me into an almost unbearable light. In a

white dress, pale and beautiful, as I had seen her the previous

night under the flickering of candles in the coffin, Aglaja stood

in the window of a passing car. I recognized her immediately.

Golden red curls blew in the wind around her forehead, her

beautiful gray eyes were fixed on me with sweet terror, and the

small hand that rested on the wooden bar of the lowered

window, suddenly loosened itself and pressed upon the heart

beneath the young breast.

Oh, I saw that she was no different from me, that she

deeply felt that we still had to pass by each other without being

able to hold on to each other, that we were not yet permitted to

unite into one blessed being, the divine consisting of the soul of

man and woman. Certainly she only felt what I knew. But this

feeling of the woman corresponded to the knowledge of the

man and was as valuable and in this case certainly as painful. It

was only a short, agonizing moment, when I was allowed to

see with bodily eyes what once, measured against eternity, was

no less fleeting and transient, and had been close. And it

became clear to me that my way to perfection was still quite far

and that many impure things would have to fall away before I

could enter eternal peace as a perfected one. I was only a

returned one.

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 265- 269

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged family, fiction, life, love, writing on January 24, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

Over and over again they went about to create new life.

They hid themselves from the others and became one. All

beings, which were invisible to the people, but always surround

them, retreated before the divine, which emanated from the

procreators, however barren and poor they might otherwise be,

as flawed and weak, but in this action they unleashed the

elemental power of eternity, they were more powerful and

greater than all other creatures. I was fervently attached to such

pairs of people everywhere. In the black nomad tents of the

steppes, in dim snow huts, in thin beds, on haystacks, behind

stacks of boards, in the bushes of the forest, on the straw

mattresses of dull houses, in garrets and state rooms. In

countless places, at secret hours of the day and night. The law

was above me. I felt attracted and repelled, without grief,

disappointment or impatience.

Once it happened, quicker than the lightning flared up.

At the union of two cells, the power of new life enclosed

me. I was caught in tiny union, caught up in hot, red, radiant,

working and pulsating being. I felt warmth, darkness, moisture,

currents of nourishment, the rustling of creative forces. Blissful

growth was in me.

Juices flowed through me; the thunder of unfolding and

the soft crackling of becoming were around me. Consciousness

became dim. Sleep enveloped it, happy, refreshing sleep. Torn

and incoherent experiences passed through my dreams as

unrecognizable silhouettes, disjointed and inaudible, ancient,

lost, sinking memories.

I grew in slumber, stretched my limbs out comfortably,

smacking with pleasure, stretched, moved softly in sleep.

Delicate and precious organs, protected in bony armor, were

formed in me, warm blood raced through me in rapid,

throbbing beats, friendly tightness pressed me tenderly, moved

me swaying, showing me the way to the light.

Crystal, cold, clear air rushed into my lungs.

Colorful, confused rays penetrated my eyes, confused

sounds pressed into my ears. Everything happened to me that

accompanies young life when it enters this world.

I was there. I was the one who had come back, the Ewli.

My name was Sennon Vorauf.

I had a father, a mother and other people who loved me. I

learned to speak and walk, a child like other children.

Everything was new to me, a great revelation.

Until the ability to look back into my past life.

This began with dreams of anxiety in childhood, which

caused my good parents a lot of worry. But even when I was

awake, I was not safe from sudden sinking. The memories of

Melchior Dronte, the son of a nobleman in days long past,

came back to me fiercely, and frightened me very much. Only

slowly did I gain from myself the repetitive, chasing, and

frightening memories and gradually put them together so that I

could grasp them as fragments of a former whole, which I

called the life of Melchior Dronte, my former life.

Shaken by the horror of my parents (they often both sat

by my bedside and listened, stunned by my wild fantasies, as

they thought), I withdrew already in boyhood and showed

myself to others as a strangely precocious, quiet and thoughtful

child, who preferred to sit alone staring with open eyes.

My new life was suitable for such thoughtfulness. My

parents, good-hearted and simple people, had, following a

custom of the country, named me “Sennon” after one of the two

saints of my birthday and loved me more than anything. After

ten years of childless marriage, I was the eagerly awaited “gift

from heaven” sent to them. In the first years of my life, I had,

as already mentioned often caused them great fear and worry.

Thus I had once fell into severe convulsions when, by accident,

I was present when a few boys threw stones at a black dog, so

that it ran away howling. To an aunt, who loved me tenderly, I

did not want to go to her until the squawking parrot, which she

had in her apartment was removed.

Sometimes one, such as the reader of this book,

understandably took these behaviors for stubbornness and

punished me mildly. The patience and the lack of any

consciousness of guilt, with which I accepted the gentle

punishments, however, soon made it completely impossible for

the good-hearted to act against me in such a way.

Especially my mother, who despite her low status was an

unusually sensitive Frau, who with her trained intuition,

recognized better than my father, that all the violent emotional

expressions of her child must indicate quite unusual mental

processes which ruled out any crude influence. I clearly

remember a Sunday afternoon, when I was with her in a garden

filled with the deep glow of the autumn sun. She had cut

flowers to put in a vase. The arrangement of the copper, blue,

white and fire-yellow Georgiana flowers she had made

suddenly seized me in a very peculiar way, and without being

able to explain where these words came from, I said

completely lost in a dream and quietly to myself:

“Aglaja also arranged them like this”.

Then my mother looked at me with a very strange, shy

look, stroked her hand over my hair and said to me:

“You must have once loved her very much -.”

We then spoke nothing for a long time, until it became

completely dark. Then mother heaved a sigh of relief, hugged

me fiercely and we went into the house to wait for my father,

who was working in a large optical company.

I had little contact with other children, and generally kept

away from them, not because I was arrogant or afraid of people,

but because I had no taste for their games. I still liked best to

be with the son of a well-traveled doctor who lived in our

neighborhood, with Kaspar Hedrich, who was the same age as

me, and who, like me, was a quiet and lonely boy. I went on

many hikes in the surroundings of the small town that was my

home, and to him, as the only one, I sometimes told my dreams,

but only when I was in my twelfth or thirteenth year, did the

realization dawn on me of the nature of these ever-renewing

and complementary dream images and what they were. From

then on I kept them to myself and did not listen to Kaspar’s

vehement pleas to tell him more. In any case, he was the only

one who listened with great attention and without any sign of

disbelief until then to the tangled stories that often violently

forced themselves out of me, perhaps only in the unconscious

longing to find an explanation for them. When this finally came

like a revelation, I guarded my secret in the realization that it

could hardly ever be understood correctly by others.

Then something happened with Kaspar Hedrich and me,

which at that time filled me with great uneasiness. Today,

however, I must think of the event with a smile and am filled

with consolation, of an event that was my first, dearest, greatest

and most valuable confirmation of the special pardon that I

have been granted.

Kaspar and I had a special joy of walking on cold winter

days on the frozen dead branch of the river to a place where we

could ice skate that was a half an hour’s walk away. We kept

this place of our solitary pleasures from our parents, knowing

that they would not have allowed us because of the danger of

both the remoteness of the water and the uncertainty of the ice

conditions. They thought nothing other than that we, like the

other boys, were on one of the two busy and completely safe,

artificially created skating rinks of the town. The deception

succeeded all the more, because neither of our fathers, who

were busy during the day nor my mother, who was absorbed in

the economic worries of the day (Kaspar’s mother had been

dead for a long time), had ever found time to teach us skating

skills.

On the day I want to tell you about, Kaspar came to us

with the skates on his arm to pick me up. There was a warm

wind that had sprung up, and water dripped softly from the roof.

All the more reason, thought my playmate, to hurry in order to

take advantage of the last opportunity of the departing winter.

However, I had caught a cold the day before and was

feverish. My worried mother, who came into the room during

the visit, explained that in view of my condition Kaspar would

have to do without my company this time. I was always

obedient to my mother and complied. Kaspar was disappointed

to have to do without his comrade, but then he said goodbye

and went on his usual way to the lonely river place alone.

After about an hour, my mother took a pillow and

lovingly made me sit on the bench by the warm stove and lean

against the cushion. She herself did some work and advised me

to take a little nap, and I soon heard her knitting softly rattling

half in a dream. All of a sudden it was as if I could clearly hear

the voice of my friend, who repeatedly and in the highest fear

called my first name!

I wanted to rise, but I was paralyzed. I made a

tremendous effort. Then it happened.

Suddenly I found myself outside my body. I clearly saw

myself, sitting on the stove bench with stiff, wide-open eyes,

with my unsuspecting mother at the table, lost in her counting

meshes at the table. In the very next moment I found myself, as

if carried away by a whizzing gust of wind, at the edge of that

river arm. With the greatest sharpness I saw the leafless pollard

willows, the uniform gray of the ice, the snow eaten away by

the warm wind, the skate tracks on the slippery ice and in the

middle of the cracked ice an open spot of the water, from

which, screaming in fear, Kaspar’s head protruded, and his

wildly beating hands that searched in vain for a hold on the

breaking ice sheets.

Without any reflection I stepped across the ice to the very

edge of the collapse, reached out my hand to the man in the

greatest need and pulled him without the slightest effort onto

the solid ice. He saw me, chattering with his teeth from the

frost, and yet laughing with joy, and opened his mouth to say

something —.

Then something pulled me away from him with terrible

force and I was seized by an unparalleled feeling of fear, and I

became painfully aware of my own distressed body —

The Return of Tradition

Posted in Uncategorized on January 23, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 260- 264

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged fantasy, fiction, horror, short-story, writing on January 23, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

The way was not too long. I looked once more with the

old eyes that had seen so much during my existence, and

enjoyed the colorful multiplicity of the images that showed

themselves to me. I saw the butcher with a steaming, scalded

pig in a wooden trough, and the brass basins of a barber, which

rattled in the wind and rain and hung full of little drops. I took

the pitying look of two dark, beautiful girl’s eyes under a blue

and white bonnet, noticed a black dog that reminded me of

poor Diana, and smelled the strong, sour-tart smell of fresh tan,

coming from a tanner’s workshop. A steel blue fly with little

glass wings sat down on my knees and thus traveled quite a

distance without effort of its own. A bunch of funny screaming

spiders, uninvolved in humanity threw themselves like a brown

cloud over the smoking mountain of horse manure, which came

from one of the front wagons, and an ancient sycamore tree, all

hung with water beads, morosely and indifferently let us pass

by.

And then, with a jerk, all the wagons stopped.

We had arrived at the ugly square, where not long ago I

had spoken with the young officer about the French nation, and

my gaze fell on the gaunt reddish-brown scaffold that towered

high above our heads, with ghastly simplicity.

At that moment the wall of fog broke, and a pale ray of

sunlight fell with dull glint on the slanting knife high up under

the crossbeam.

“How soon all this will be over!” I thought, and

remembered so many moments of impatience and not being

able to wait, which lay far behind me in the old days.

We had to descend, and we were helped to do so. The

people did not shout. There was only that quiet murmur of a

thousand voices that betrayed the excitement of a great crowd.

No one shouted swear words at us, and many eyes looked

sympathetically. I had the feeling that with such a general

mood, the great killings would soon subside and finally stop

altogether. My knees were stiff from sitting and from the

morning chill. The distress of the body cramps set in once

again, and the right hip was very painful when walking.

I saw people appear on the platform, appearing to move.

The knife fell with a dull clang and was raised again. It was red.

Something struck the boards of the bloody scaffold.

The fear of the body almost gained the upper hand. A

thought pushed forward, gained space: To do something to save

myself, to scream, to beg, to break through the crowd, to break

the cords…

That’s when I saw him…

Huddled like a bat. Fangerle. He was sitting on a lantern

of the gallows, grimly distorting his wide mouth, the evil

yellow eyes directed at me, a red, Phrygian cap on his skull

instead of a big hat. His eyes were like two wasps that lived

and crawled around in the cavities of his head.

I closed my eyes. My will kept the upper hand.

“Return to the depths!” I said to myself.

When I looked again with all my strength, the apparition

had disappeared, the pole was empty.

A soldier grasped me almost timidly by the arm and

pushed me forward with gentle force. I saw how clotted, thick

blood flowed sluggishly down the boards of the scaffolding.

Before me the Marquis de Carmignac climbed the slippery

little stairs. Two men with naked arms grabbed him, strapped

him to the board, and tipped it over. The upper part of the wood,

which enclosed the neck, lowered. Whoosh…

A whistling sound came from his headless neck. The feet

with the buckled shoes, manly still in death, softly tapped the

ground, his body moved in the straps, as if he wanted to make

himself more comfortable. They loosened the damp leather,

rolled him aside; the golden pear rolled over the boards, a little

lid opened, brown snuff dusted out. Quickly a hand reached for

the shiny thing.

I was next, climbing the stairs.

A hand supported me kindly, saved me from a fall in a

moment of slipping. I looked into a serious, well-cut face. It

was Samson. He made a polite inviting hand gesture. Behind

him stood the red-bristled monster.

Images circled in my brain in a flash. The arm with the

executioner’s sword in the witch’s room of Krottenriede, the

box with the singing little bird, burning candles in a black room,

the glitter of Aglaja’s crown of death, the little dead man with

the hourglass and the scythe, as it tilted out of the old clock, the

Bavarian Haymon as an Amicist —Firm hands grabbed me by

the arm. Faces slid past me. I stood at the board. The warm

smell of blood rose to my nostrils, tickling and irritating in the

nose. Thin straps snaked around my upper body, my legs. I fell

forward — it creaked softly around me, – pain- my larynx hit a

semicircle.

I thought: Now the knife will cut through my throat,

sawdust will fill my eyes, my mouth —.

Wet wood descended on the back of my neck.

Isa Bektschi! Isa Bektschi!

With all my might I thought of the Ewli. I forced him to

me.

Close to mine I saw his face – his mouth, as if he wanted

to kiss me – kind, dark eyes, like two black suns. His gaze

enclosed me with infinite love and promise.

I thought nothing more. I saw only him – drank his looks,

absorbed his essence into me. Then dazzling, golden rays shot

out from his eyes, piercing me, consuming me in fiery embers –

in golden fire.

But still I saw that face, clearly, sharply, saw it growing

smaller and smaller – small as a dot and yet recognizable -.

I opened my mouth, felt woody, dry splinters, moist

chunks—.

Then night — hissing — sound — a painful tearing – a

thread cut in two —

I found myself outside my body. My body lay in its

brown, rumpled suit, without coat, with blood-soaked shirt

edge on the board of the guillotine. Despite the tight straps, my

upper body reared up a few times violently. Fountains of blood

rushed out of the two large neck veins.

The head lay pale, with wide-open eyes in the basket. Its

face smiled. All the people who were standing around the

scaffold looked on in silence. The board became empty. The

man who had called Astaroth and the fiery dragons was

dragged up the steps. He struggled with all his might, kicking

with his feet, snapping his teeth.

He did not want to – – All this was so indifferent for me. I

rose and floated away over the many heads, glided effortlessly,

and without finding any resistance, through the house walls and

window panes, driven by a force.

I had no eyes and saw everything. I heard. But I felt

nothing. I thought nothing either. I was consciousness itself.

Everything came to me, was immediately recognized.

Vibrations of many kinds trembled through me, without me

feeling pleasure or suffering. It was coldness, warmth, a sound,

light, phenomena for which there are no words in human

language, sensations when encountering beings, that remain

invisible and unknown to people.

I was of a shape, if this is possible to say, like those

glassy-transparent bodies that glide past human eyes when they

look for a long time into the distant pure blue heavens.

Nevertheless I was not a body. I was also not nothing. I was a

soul, like many of those who floated in the world space. But I

had consciousness, I was mindful of my ego and I had a goal.

I was looking for a new house with those instruments of

the senses, which received from outside and could reflect from

the inner back to the outer: Could express thoughts as words. I

was looking for a human body. Inside me I carried the tiny

image of a noble, godlike face, the reflection of which I had

taken with me into infinity when I left the destroyed body.

From this image my consciousness extended along with the

ability to remember.

The will for re-embodiment was the only drive that

dominated me. According to inscrutable laws born of the

eternity of becoming and passing, I strove towards my goal,

devoid of all those feelings that can be called impatience,

expectation or hope. There was no time; there was no distance

and no obstacles.

Forces to which I surrendered of my own accord

willingly lifted me up, made me sink down, and made me to

fade away, to wander and to rest.

I was unmoved in my consciousness.

Everything was offered to me, nothing was hidden from

me, and nothing was veiled, neither in depths nor in heights.

The wind blew through me, the rain fell through me. I had

nothing of the properties that things in space possess. I was big

and small, inside and outside, far and near.

I saw sunsets in ocean wastelands, mountain hikers

crashed in crevasses of ice, blue flowers that slowly withered,

ghosts in waterfalls, beings that lived in crystals, red and

yellow sandstorms, and fermenting garbage, out of which new

creatures of the strangest kind sprang, dwarfs, who would have

appeared as stones to human eyes, winged creatures that rode

and roared, sleeping in beds, seeded with tiny goblins as with

vermin, people, from whom evil flowed like a poisonous breath.

I passed by all this.

There were animals in herds on vast steppes, animals in

the air, in holes in the ground, in the water. Small, crawling,

flying, running animals, animals of all kinds, covered with hair,

feathers, scales, bristles and plates, living animals. They

attracted me because they were alive. They begat young,

hatched them, reproduced thousands of times.

They attracted me strongly, because they had living

bodies, warm bodies. But I carried in me a human face and did

not follow those souls, that lurked waiting to enter into the egg

cell at the moment of conception.

I was only attracted to people. I was attracted to them by

a tremendous force.

It was good to be with people. I attached myself to them,

was with them, in them, slid through them and was a guest with

others. I lived with them. I saw them as one sees a region that

resembles the abandoned homeland. I have to use such

comparisons, although the truth is quite different.

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 255- 259

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged family, fiction, life, love, writing on January 22, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

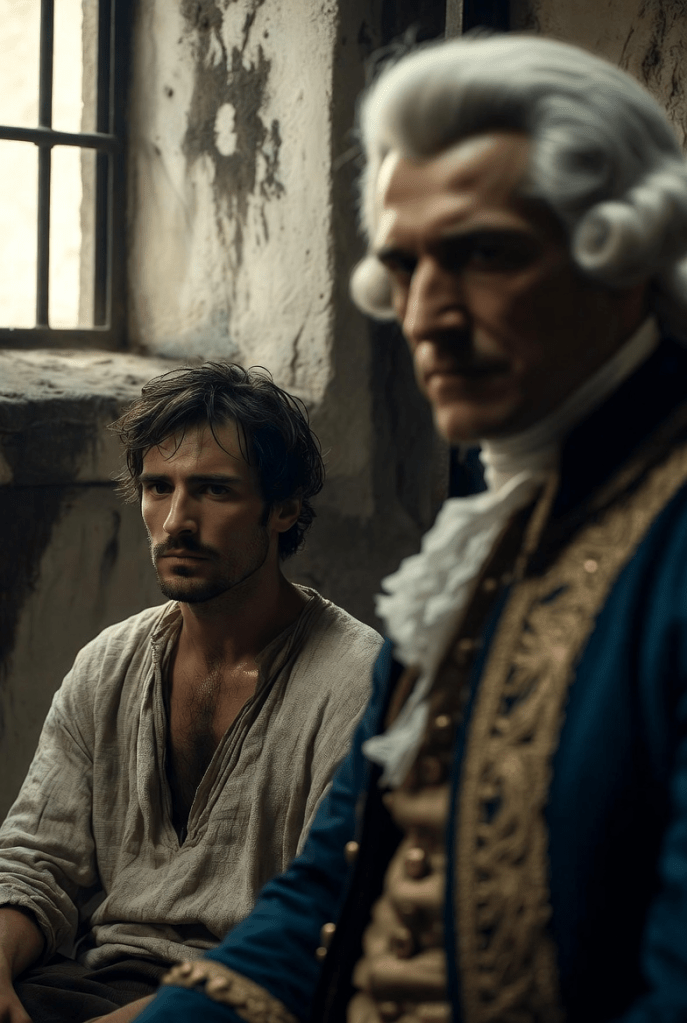

I went near one of the windows, unfolded the paper and

read:

“My heart weeps for the best and noblest of men; yet I

bow before a heroism that respects death less than the betrayal

of itself. My now impotent gratitude will forever honor your

memory. May there be a reunion that gives you new goals.”

It was the well-known handwriting of the magister.

In the dim morning light we could see through the

windows, which were high up but clean and bright, that a fine

rain was falling outside. Drops hung sparkling on the iron bars

of the lattice.

This dungeon, admittedly the last one in which we were

housed, was in every respect friendlier than the gloomy coal

mine where we had awaited our sentencing. A bow-legged

jailer with a good-natured face and a natural gift for joking

words, brought us washing water in wooden cans and lent us

clean, coarse cloths to dry our faces and hands. For those

prisoners who still had money on them, he provided chocolate

for breakfast and pieces of cake. The others were given a soup

of burnt rye flour and a large slice of bread.

Since everything seemed trivial to me that was still

connected with the needs of the body, I was content with a few

spoonfuls of soup. Also in these last hours of my life, I

sometimes felt as if I were completely outside the events and

saw from afar, like an observer, me and my fellow sufferers.

Nevertheless, this observing being, which was my ego, was

connected by a guiding thread with my body, and felt the

morning chill, hunger and that dull, constricting feeling in the

stomach area, which precedes bad events. This strange out-of-

myself sensation was so strong that my own hands seemed like

something foreign, for I looked at them closely and with a

strange feeling as if I were seeing something familiar again

after a long time. In all these ambivalent feelings was mixed

with a kind of regret over the ingratitude, with which the soul

calmly left forever, the house in which it had been for so long

and through whose senses it had taken in the image of its

changing surroundings. I could not, try as I might, find

anything great or decisive in the imminent departure from the

accustomed form of earthly life. It was as if the body, although

its sensations continued, no longer participated in those of the

soul.

Even the scenes that took place around me could not

move me violently, as much as I was aware of their sadness.

Something constantly stirred in me, as if I had to speak to the

poor people and tell them that all this was only of secondary

importance and that it did not really have to mean much. But it

was also completely clear to me that they would not have

understood me at all, and so I kept silent and out of the way.

Many things happened around me. Women wept bitterly

and their hot tears, with which they said goodbye to life,

dripped into the soup bowls from which they ate. The Marquis

de Carmignac sat in a corner and had his beard shaved and his

hair arranged. A withered, weary smiling old man read to a

small crowd of listeners from the “Consolations of Philosophy”

by Boethius. A handsome young man in a riding suit leaned

against a pillar with rapt eyes and hummed a little song over

and over again, which was obviously dear to him as a memory.

He stopped only when an Abbe, who was whispering prayers

with several older and younger ladies, approached him and

politely asked him not to disturb the religious gathering of the

dying. Several sat dully, despairingly and completely absorbed

in themselves on the straw mattresses of the beds that were set

up here.

After some time, a young, pale-looking barber’s assistant

entered with the jailer, waved to his comrade, who was taking

the marquis’ tip with many bows and with a trembling voice

asked the people present to sit down in turn on a bench placed

in the middle of the room, to have their hair cut. This request

caused loud sobs and a fit of fainting, but the toilet, as the

procedure was called for short, proceeded swiftly. The long

tresses of the ladies, which were carefully cut off and placed in

a small basket, he very politely requested them to be

considered useful for his business, and presented each woman

who gave her consent, a small vial of smelling salts as a return

gift.

The frosty, rattling and moving of the scissor also

touched my neck, and their blades cut through my hair. Coldly

I felt the lack.

All around, the praying grew louder and more fervent. At

eight o’clock a booming drum rattled and the door opened. In

front of a crowd of soldiers, a commissar with a sash appeared

and read off name after name from a list. All those named rose

immediately and lined up to the left of the door.

“Citizen Melchior Dronte!”

I bowed briefly to those who obviously remained behind,

and stood next to a tall, strong man who, with a contemptuous

expression, derisively pushed his chin forward. By his braids

and lapels and the uniform, I recognized him as a major of the

Broglie regiment.

“Skunks – riffraff from the gutter!” he growled and spat

out so violently that a small, hungry-looking soldier jumped to

the side, startled.

A somewhat lopsided, gray-clad man with a mocking

face, who was one of those called up, laughed softly to himself.

“This carnival play will soon be over. And it wasn’t even

very funny.”

We were now; about twenty in number, led out of the

cellar, went up the stairs and came to a courtyard that was

completely surrounded by soldiers. It was still trickling thinly

from the cloudy sky. Some ladder wagons were standing there,

and we were ordered to sit on the boards nailed across. A boy

of about fifteen years old climbed up behind us and tied our

hands behind our backs with strong vine cords, supervised by a

mounted sergeant. I saw that the young lad whispered

something in the ear of each person whom he bound. And when

it came to my turn, I heard from behind, half-breathed, while

the warm breath hit my shivering neck, the words:

“Forgive me!”

I felt how restless and hot the hands were that bound my

arms.

Amidst much shouting, running to and fro, and up and

down trotting of the cavalry escort the wagons were finally

loaded with their human cargo. Next to the coachman, a soldier

swung himself onto the bench and the big door of the courtyard

opened with a loud creak. Incalculable masses of people filled

the street outside and formed two rows, between which our

carts now slowly began to roll.

Quietly, I looked around me. In front of me, stiffly erect

and looking over the people, sat the Marquis de Carmignac,

next to him the major of the Broglie regiment, who, with his

furiously lowered red head reminded of an irritated bull.

Crouched on the bench next to me was an obviously deranged

man, about sixty years old, with white beard stubble, a

wrinkled face and rolling eyes, who was intoning incessant

incantations to himself.

“O Astaroth, O Typhon, O ye seven fiery dragons, you, O

keeper of the seals, hasten to help me! Let flames fall upon

them, let the earth open up and take them to the lowest hell, but

carry me to the garden of the white Ariel Arizoth Araman

Arihel Adonai.”

The words became unintelligible, and at last he burst into

a triumphant giggle and became calm, obviously firmly

convinced of the sure effect of his spirit invocation.

I turned my head with difficulty to the back bench and

caught sight of an aging girl with brick-red spots on her

cheekbones, who was dressed in a black robe, with her eyes

turned to Heaven, praying without ceasing. Beside this nun,

who with glowing eyes, was preparing for martyrdom,

trembled like a jelly, a white-flour covered baker, whose

swollen, puffy eyes gazed out of a hot face in which mortal fear

gaped. His huge belly, which almost burst the buttons of the

trousers, wobbled back and forth with every step of the horses.

I saw excessively clearly, and not the slightest detail

escaped me. I noticed a hanging silver button on the jacket of

the marquis. On the neck of the major an inflamed pustule. On

the vest of the man sitting next to me the remains of an egg

dish, and the medals on the nun’s rosary sometimes clinked

against a board of the cart.

My poor body, which was now to change, was doing

everything in its power to keep the calm serenity of the spirit

that was preparing to leave busy with unimportant worries on

its way into eternity. A natural need, for the satisfaction of

which there was no time left to satisfy, arose with annoying

agony. An old cold pain which had not tormented me for a long

time, had shot into my right hip during the night and caused me

great agony with the shocks of the cart. And to all this was

added the fear of death that the body felt. It manifested itself in

strong stomach pains and finally brought it to the point that

cold drops ran down my face. It was cold sweat, death sweat…

But I stood above or beside these sensations which, in

spite of their strength, could no longer really penetrate to the

consciousness. A sharp and irrevocable divorce between body

and soul had occurred, and the soul realized with joy that no

earthly feeling would accompany it on its way.

From the crowd a song burst forth in full chords, into

which thousands of voices fell. The truly entrancing melody,

the words of which I could not understand, except for

“Fatherland”, “tyranny” and the like, had a strong and moving

effect on me. It was a genuine and noble-born, fiery child of

the time, and it was as if this rapturous singing carried

something hot in it.

Everywhere people were looking out of the windows of

the suburban houses, joining in the song with bright,

enthusiastic voices and waving their scarves. The horses in

front of our wagon, a chestnut and a summer black, neighed

and began to prance and nod their heads in time with the

mighty tune, which was glowing and storming up to the sky.

Even the driver, a scowling man, and the young soldier next to

him sang the hymn, for such it was, with a loud voice.

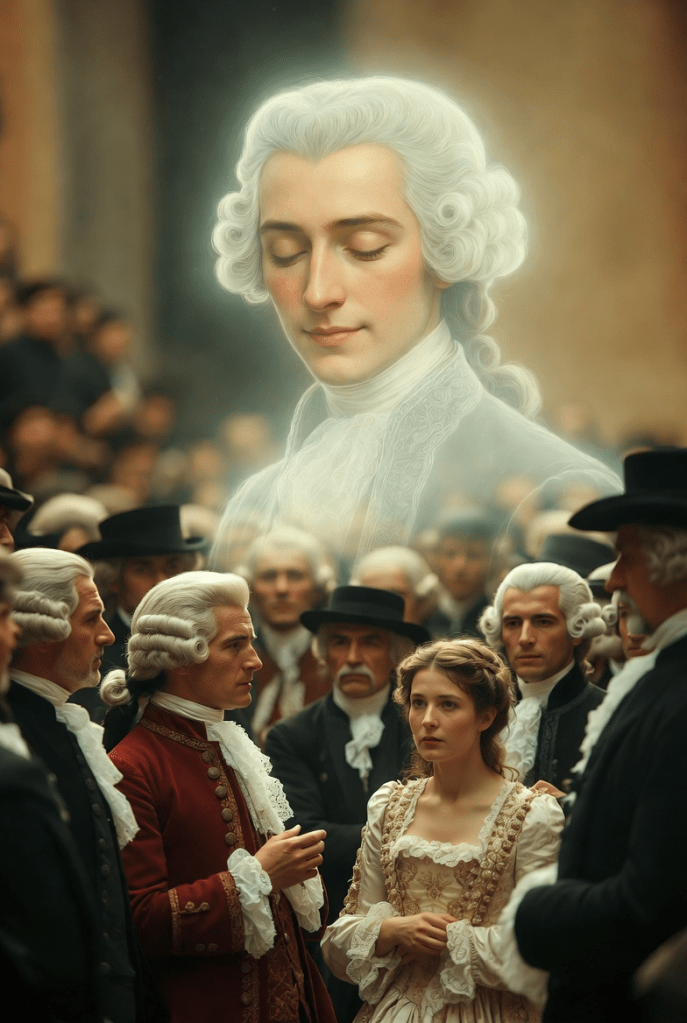

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte: pages 250- 254

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged books, fantasy, fiction, short-story, writing on January 21, 2026| Leave a Comment »

The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

“I wanted to protect the defenseless woman,” I said,

looking him in the eye. He shook his head reluctantly.

There was a murmur.

“Are you a friend of freedom?”

I thought for a moment and then answered the question

with a “yes.”

“Was it known to you that citizen Lamballe had fled to

England and returned from there to Paris?”

“Yes.”

“In that case, it was reasonable to assume that there was

valuable information about her co-conspirators located here

that could be obtained. Not so?”

I was silent.

He looked at me again with a quiet, disapproving head

movement and with a tongue-lashing spoke slowly and clearly,

emphasizing each word:

“I know what you are trying to say, Citizen Dronte. In

your zeal to serve the republic and prevent a premature and

early end of the traitor, you have sought to use violence to

prevent the execution of the sentence. However, you fared

badly enough. Is that so? Give me answer!”

He nodded an almost imperceptible “yes” and waited.

I felt briefly and strongly the lure to return to freedom

from the horror of this justice. But a powerful, insurmountable

feeling inside me made the friendly images of imminent

freedom quickly fade away. I realized, like a holy necessity,

that I had to be hard and merciless against myself, otherwise I

should be thrown back into levels from which I had ascended

and not allowed to higher ones whose aura I had attained.

“I have tried to save the princess on the basis of feelings

of a personal nature!”

The chairman heaved a sigh of annoyance, swayed his

head, drummed on the table and raised his eyes to the ceiling.

The committee members looked at me bored, and in the

auditorium a yawning voice said:

“These are quibbles, Jeannot – Do you understand any of

it?”

“In a nutshell: you had no intention of protecting the

woman as such, but rather to render a service to the Republic.

We have no time, Citizen Dronte, and I hope that your sincere

admission of this fact will settle the case!”

A cold breath passed over my face. The scales stood: a lie

had to sink the bowl —

“I did not think of the Republic in my deed!”

Now it was spoken.

Great unrest arose. Even the drowsiest among the

listeners understood, awakened to irritated attention. The face

of the chairman turned red with anger. He threw his head back

so that his hair flew and hissed at me:

“You dare tell me that?”

“It is the truth,” I replied.

It was clear to me that the grateful magister must have

had his hand in this, and it saddened me that his not without

danger effort had now been in vain. But I had to follow the

path that my innermost feeling was the right one, to go to the

end, regardless of the feelings that arise from the body’s

instinct for self-preservation.

The behavior of the chairman changed immediately. A

deep vertical wrinkle appeared between his eyebrows, and he

bit his lips angrily before continuing the interrogation.

“You are a stranger. For what purpose did you come to

Paris?”

“To become acquainted with the Revolution and its aims-

.”

“With friendly or hostile intent?”

“I did not come with hostile intentions.”

“You are a baron. – How can an aristocrat’s opinion of the

Revolution be otherwise than hostile?” suddenly the bilious

committee member intervened.

“Does such a person love the poor people -?” growled the

one with the stained red cap. “How?” he turned to me.

“I love all the people.”

“These are sayings such as every priest has in his pocket

who stands before the tribunal,” the judge snapped at me and

assumed a frowning pose with a lurking look at me. “You have

thus joined the brave ones who have gone the Lamballe way,

not in the interest of the state, but in order to protect the queen’s

intimate for some other dark motive.”

“Don’t make such long stories!” grumbled someone

behind me.

“He’s one of the whore’s lovers, nothing else!”

Shrill whistles sounded.

Wild stomping of feet revealed that the people wanted an

end.

The skinny man talked to the chairman. The latter

shrugged and turned to the other committee member, who

nodded his head vigorously, raised his right hand and dropped

it with the edge on the table. It was clearly understandable what

he meant by this.

The chairman stood up, stretched out his right hand

toward me like a king of the theater, while the left hand rested

on his heart, and spoke with his voice low and rolling the R’s:

“Citizen Dronte is guilty of treason against the

Republic!”

Thunderous clapping of hands resounded. I sat down,

completely calm and certain of the end.

Then the man in the dark blue, gold-embroidered jacket

slowly turned his stern and stony face toward me, smiled and

said very loudly and audibly:

“Allow me, Baron, to express to you my sincere esteem!”

Laughter and jeering followed his words. An apple case

flew past my head and remained in front of the judge’s table.

The theatrical chairman slammed his fist on the table and

shouted, “Quiet!”

Gradually, the scolding, laughing and whistling ceased.

“Citizen Carmignac!” rang out the complacent voice.

The man in the blue jacket stood up.

“I am Philipp Anton Maria Marquis of Carmignac, Pair

of France, Privy Councillor of His Majesty the King, Chairman

of the Breton Chamber of Nobility, Commander of the Order of

Louis —“

The hall cheered. This tall man and his proud manner