The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

The magician: “O Sheikh, I am going to the other world;

procure for me a right in the hereafter!”

The Sheikh: “I can give you one piece of advice; If you

follow it, it will be for your salvation.”

Turkish legend

“When the angel of death touches your heart, the soul

leaves its narrow house, faster than lightning. If it can take its

memory along with it, it remains aware of its sins. This is the

path to purity and that of the entrance to God.”

Secret Doctrine of the Beklashi

What I am writing down here, hoping that it will fall into

the right hands according to the will of God I, Sennon Vorauf,

have experienced in that physical existence which preceded my

present life. These memories have come to me by a special

grace beyond that transformation which is called death.

Before I realized this, I suffered from them and thought

they were inexplicable, agonizing kinds of dreams. Besides,

however, I also had to go through all kinds of shocks of an

unusual kind. It happened, for example, that the striking of an

old clock, the sight of a landscape, a fragrance, the melodies of

a song, or even a mere association of words would assail me

most violently with the thought, that I would have quite

certainly already once heard, seen, breathed in, or somehow

experienced it before. I was in this or that place, which I saw in

my present life for the first time, and already had once been

there. Yes, often enough, in conversation with new

acquaintances, I was struck by the idea that I had already been

in very special relations with them. Since it was impossible for

me to understand before the onset of this realization, it was also

impossible for me to provide explanations for the indescribably

exciting movements of my mind and emotions, much to the

grief of my parents, which often led into hours of brooding, the

unknown cause of which disturbed them not a little. But

through frequent repetition and the ever sharper imagery of the

story I became aware, even as a boy, that they were nothing

more than reflections of fates which my soul had suffered in

another body, namely before the birth of my present body;

moreover, these “Dreams” represented experiences that were

completely alien to my current circle of experiences and

frighteningly distant from my present circle of thoughts. I had

never heard of such things or even read about them somewhere

or otherwise experienced them. I began to record these

“dreams” of my own accord and thereby achieved that from

then on in certain favorable moments I had the so-called

wakefulness to remember such memories with extraordinary

accuracy.

More and more clearly and coherently from these “lucid

dreams” (as I called them in my case) the overall picture of a

life emerged that I had lived before this under the name of a

German nobleman (I will call him here Baron Melchior von

Dronte), had lived and ended, when his body fell to the

transformation of death and then became free to be my soul as

Sennon Vorauf.

In the peaceful and blessed life filled with inner peace,

which I lead, the retrospective view of the wild and

adventurous existence of Melchior von Dronte broke through in

a disturbing, confusing and frightening way. What he was

guilty of was my guilt and if he atoned, he atoned for the soul

that came back, for his and therefore my soul.

I am fully aware that many people will read this book

with incredulous smiles, and perhaps in some places at times

with disgust and revulsion. But at the same time I hope that the

number of people of deeper feeling will be large enough not to

let this writing perish. To those who are able to remember

details from previous forms of existence, who are conscious of

a previous life, I would like to dedicate this book to them; I

would like to make this book their own.

Just as I have replaced the real name I had with “Dronte”,

I have replaced those of various persons, whose descendants

are still alive, with invented names. Moreover I touch here the

fact that I have called people “Dronte” in this life, whom I

knew from the time before my death. Most of them were not at

all aware of a previous existence. Nevertheless, there were

moments and occasions with them, in which clearly

recognizable flashes of memory flared up in them in a flash of

recognition, without them having succeeded in determining the

source of such disturbing feelings or having the ability to hold

on to them. I am certainly not saying anything new to those

who, like me, have brought parts of an earlier consciousness

into the new life.

The raw, crude and often coarse nature of the following

biography of a life, I could not in truth love, as unpleasant and

hurtful some of it may seem. I was not to embellish and smooth

out the terrible clarity with which the memories surfaced in me,

and thus to write a pleasantly readable book. Everything had to

remain the way it was as it formed from a time whose spirit

was different from ours.

However, from the deepest, most personal feeling this

book should speak to the immortality of the soul, and this

confession is to possibly awaken this confession in others.

Above all, I am inspired by the hope that those who believe in

the wandering of the soul after the death of the body will not be

given completely worthless indications in this book. Others

who have not yet progressed on the path that I have walked,

may still at least read it for the sake of its colorful content.

I remember very clearly an incident from my fifth year of

life.

I had been undressed, as always, and lay in my pink

lacquered, shell-shaped child’s bed. The warm summer evening

wind carried the chirping of many insects into the room, and

the wax candle in a silver candelabra flickered. It stood on a

low cabinet next to the glass lintel, under which the “Man from

the East”, or the “Ewli”, as he was also called, was located.

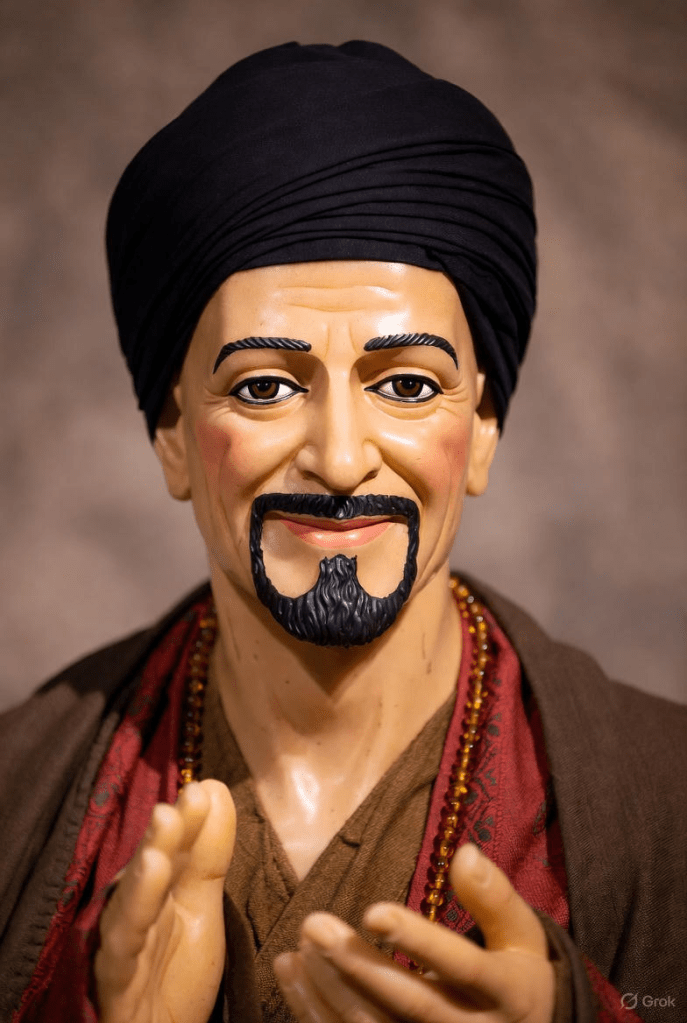

This was a span-high, very beautifully formed figure,

which a relative, who was in the service of a Venetian, had

brought from there as a gift from the nobility.

It was the figure in wax of a Mohammedan monk or

dervish, as an old servant often told me. The face had the

sweetest expression for me. It was completely wrinkle-free,

light brownish and with gentle features. Two beautiful dark

eyes shone under a jet-black turban, and around the softly

curved lips a small black beard could be seen. The body was in

a brown-red robe with long sleeves, and around the neck the

dervish wore a necklace of tiny amber beads. The two fine wax

hands were on arms hanging down with the palms turned

forward, equal-ready to receive and welcome anyone who

should approach. This immensely delicate and artistically

executed piece in wax and fabrics was highly valued in my

family, and for that reason alone, it had been placed under a

glass dome to protect it from dust and unskilled hands.

I often sat for hours in front of this expensive figurine for

unknown reasons, and more than once I had the feeling as if

the dark eyes were animated by being alone with me, as if there

was a faint trace of a gentle, kind smile around its lips.

That evening I could not fall asleep. From the fountain in

the courtyard came the sound of water splashing and the

laughter of the maids washing and splashing each other and

with similar shenanigans teasing each other. Also the cicadas

and crickets in the meadows surrounding the mansion were

making noise. Between all that sounded the muffled sounds of

a French horn, on which one of the forest boys was practicing a

call.

I climbed out of bed and walked around the room. But

then I began to be afraid of the moment when old Margaret

came into my room every night to put out the light in case I fell

asleep with it on, and I went back to my bed. Just as I was

about to climb over the edge of the bed shell with my bare legs,

it was as if a voice softly called my name. I looked around

frightened. My eyes fell on the man from the Orient. I saw very

clearly how he raised one arm under the glass bell and

beckoned to me.

I began to cry with fright, looking steadfastly at the little

figure.

Then I saw it very clearly for the second time: he waved

his hand at me very hastily and commandingly.

Trembling with fear, I obeyed; in the process tears

streamed unstoppably down my face.

I would have loved to scream out loud. But I didn’t dare,

for fear of frightening the little man, who was now very much

alive and waving more and more fiercely, in anger, such as my

father, whose short one-time wave was not only for me, but for

all the inhabitants of the house, an order that had to be obeyed.

So I went, crying silently, towards the cabinet on which

the waving dervish stood. I had almost reached him, despite my

anxious hesitant steps, when something terrible happened. With

a horrible roar and in a cloud of dust, debris and splinters, the

ceiling of the room collapsed over my shell bed.

I fell to the floor and screamed. Something flew whizzing

through the air and smashed the glass dome and the waving

man made of wax into a thousand shards and pieces. A brick

that had flown over me.

I screamed at the top of my lungs. But there was

screaming all over the house, outside at the well and

everywhere, and the dogs in the kennel howled.

Arms grabbed me, pulled me up from the earth. Blood

was running into my eyes, and I felt a cloth being pressed

against my forehead. I heard the scolding, agitated voice of my

father, the wailing of old Margaret and the moaning of a

servant. My father hit him with a with a stick and shouted:

“You donkey, why didn’t you report that there were

cracks in the ceiling? I’ll beat you crooked and lame…!”

Leave a comment