Homo Sapiens: Under Way by Stanislaw Przybyszdski and translated by Joe E Bandel

No, please, you must let me finish, I have to talk about this…

“No, not at any price; I can’t bear scenes like yesterday. Be reasonable, you’re so nervous.”

Falk fell silent, Marit choked back her tears. They walked a while in silence.

“You asked me for friendship yesterday, so as a friend, I have certain rights.”

“Yes, of course you do.” “Are you really married?”

“No, I’m not. I only have a child, whom I love beyond measure; and I want to go back to him now and live with him, somewhere in Upper Italy—yes, that’s really my plan. I love the child so infinitely; I don’t know anything I love as much.”

Marit grew nervous and silent.

“The child is really quite wonderful…”

And now Falk began to talk about the child with an unusual warmth and tenderness, all the while fixing his eyes sharply on Marit.

Marit visibly suffered.

“By the way, you probably don’t know: I was very ill in Paris, poisoned by nicotine, yes, nicotine. I would’ve probably gone to ruin if I hadn’t had excellent care.”

“Who cared for you?”

“Well, she’s a very remarkable lady. She’s very intelligent and plays the piano wonderfully. Oh yes, she has the mind of a man.”

“Is that the child’s mother?”

“Oh no, I have nothing to do with the mother.” Marit looked up at him, astonished.

“But you said yesterday that you couldn’t get rid of the lady? You said she clung to you like a burr.”

Falk grew confused.

“Did I really say that?”

“Yes, you said that; you even said that’s why we couldn’t be happy.”

Falk thought.

“Then I must’ve really been drunk. No, I don’t understand…”

He acted as if he were utterly shocked at himself. Marit had to recount yesterday’s conversation in detail.

“Yes, yes; I was really drunk. No, you mustn’t put any stock, absolutely none, in what I say in that state; I tend to make things up then.”

Marit looked at him suspiciously.

“You have to believe me; when I’m drunk, I tend to tell the wildest stories. No: the mother’s gone. I think she’s a model now, or something like that, living with a sculptor.”

Marit grew very happy; she smiled.

“So the whole story from yesterday was a comedy?”

“Yes, yes,” Falk hurried to reply, “but it was a comedy I performed in good faith; I believed everything I said.”

Marit still couldn’t understand, but she stayed silent. Falk grew restless.

“No, no, I have nothing to do with the mother anymore. The lady who cared for me is entirely different; her name is Fräulein… Perier. For two weeks, she sat by my bed, endured my terrible moods with angelic patience, and played the most wonderful stories for me; day and night, she was there.”

“Did she live with you?”

Falk made a surprised face.

“Yes, what’s wrong with that? In Europe—” he emphasized the word—“there’s great freedom in the interactions between men and women. There aren’t the foolish prejudices like here. Here, a lady can be officially engaged to someone in front of the whole world, and still the mother and two aunts have to trail behind. No, in Europe, there are no religious or conventional rules in matters of love. There, everyone is their own rule and law.

Yes, yes, it’s so free there, so free. Good God, how narrow, how unbearably narrow it is here.

There are laws and barriers and police measures; people are so confined—in a thousand idiotic: you may do this, you may not do that!”

Falk thought.

“Why did you pull away so violently yesterday? Can’t you kiss a sister or a friend, what’s wrong with that?”

“No, I couldn’t do that. I’d have to despise myself. I wouldn’t be able to look you in the face freely. And would you have even a trace of respect for me?”

Falk laughed loudly with open scorn.

“Respect? Respect?! No, where did I lose that word, what is it even? No, I don’t know the word or such a concept at all. I only know free women who are their own law, and then I know women who are slaves, pressing their instincts into idiotic formulas. And among these slaves, I distinguish women with strong instincts, with enough power, beauty, and splendor to tear apart the foolish ropes with proud, victorious majesty, and then women with weak instincts—in a word: the livestock that can be sold like any other commodity, obedient like any other household animal.”

“So you must highly esteem the woman who bore your child and then ran off to another?”

“No, because I don’t know esteem. She only went where her instincts drew her, and that’s surely very beautiful.”

“No, that’s ugly, despicable!” “Hmm, as you wish.”

Marit grew very irritated.

“And that Fräulein—what’s her name?—Perier.”

“Yes, then you’d have to see Fräulein Perier as the highest ideal; why don’t you love her then?”

“Of course, in fact, Fräulein Perier is the most intelligent woman I’ve met—”

Marit flinched.

“That I don’t love her is only because the sexuality with which you love is completely independent of the mind. In love, the mind isn’t usually consulted.”

“So those are the women you like!”

Marit was nearly crying. This Fräulein Perier was a bad person! Yes, she knew it for sure.

“Yes, yes, yes; that’s how you judge from the standpoint of formulas and Catholicism.”

Both fell silent. Falk was stiff and curt, making it clear that further talk was pointless.

Marit suffered. She felt only one question: why had he told her all those stories yesterday about the woman who clung to him like a burr.

“So the mother ran off from the child? Falk, be open! I tormented myself all night over this; I beg you.”

“Why must you know that?” “Yes, I must, I must.”

Falk looked up at her, surprised.

“Yes, I told you. Besides, how could another woman care for me if she were with me?”

Marit calmed down. So he had no woman with him. She was almost grateful to him. From time to time, she looked at him; there was something in her gaze, like a child who wants to apologize but is too proud.

Falk stared stubbornly at the ground. They reached the garden gate.

“Won’t you stay for dinner? Papa would be very pleased. Papa asked me to keep you. He has so much to discuss with you.”

But Falk couldn’t possibly stay; he was very polite, but icy cold.

Then he left, after bowing very correctly.

Marit watched him for a long time: now he must turn back to her. Falk walked on and didn’t look back.

My God, my God, Marit sighed in agony; what have I done to him?

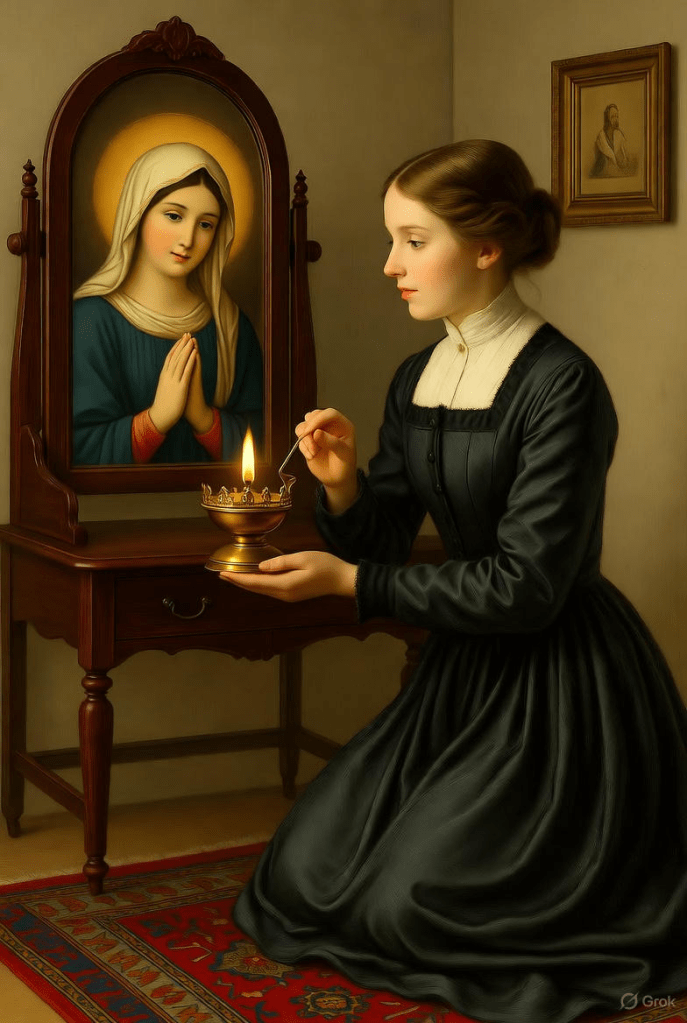

She went up to her room and lit the oil lamp before the image of Mary; then she knelt and threw herself on the floor before the gentle, smiling face of the miraculous Virgin.

Leave a comment