OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

“No, there’s nothing to be done with you,” sighed Reichenbach, “no more with you than with Hermine or Ottane. It clearly requires a special disposition.”

“It seems so!” said Schuh, concerned.

“You still haven’t fully grasped the importance of my experiments.” And now the Freiherr becomes solemn like a priest opening the innermost sanctuary: “It concerns, namely, a kind of rays, a radiant force, a dynamis emanating from people and things.”

“Indeed!” says Schuh, making a face like a schoolboy rascal.

“A new natural force, understand! Or rather an ancient one, but only now discovered by me. And its laws are already outlined in broad strokes before me. All people, all things emit rays, positive and negative, mostly bipolar, especially humans. They are charged with dynamis, unequally named left and right, top and bottom, front and back. And it’s like everywhere in nature—the unequally named dynamis of two people, even of the same person, attract each other; the similarly named repel. That’s why the Hofrätin finds the touch of her left with my right pleasant, the touch with my left repulsive. And vice versa. When she folds her hands or brings her fingertips together, the dynamis equalize, become similarly named, and that feels unpleasant. The sheet of paper on the fingertips is painful because it hinders the dynamis’s radiation. The water glass from the left hand or in the shade is positively charged, thus repulsive; that from the right hand or in the sunlight is negatively charged, thus cool and pleasant.”

“Aha!” says Schuh and feels compelled to offer a word of understanding. “Magnetism! Animal magnetism!”

“No,” Reichenbach shouted angrily, his face turning red, “not magnetism. Don’t talk such nonsense. You should finally understand that.”

“Dear Baron!” Schuh feels the need to intervene seriously now. “Dear Baron, I wouldn’t want to base new natural laws exclusively on the esteemed Frau Hofrätin Reißnagel.”

“She won’t be the only one, certainly not. Many people indeed drift along dimly and dully like you and Ottane and Hermine, but there must be a whole host of others with heightened sensitivity, sensible people. Where does it come from, that so many people can foresee the weather, why do some not tolerate the close proximity of many people and faint, where does the mysterious attraction between two people at first sight come from, or the equally baseless aversion to someone met for the first time? I will search; I will repeat my experiments with others, and you will see what meaning and connection emerges from it.”

“I’m afraid I won’t be able to witness your investigations,” says Schuh, “I must travel.” Yes, Schuh actually has no particular reason to be cheerful, not the slightest reason, and only the irresistible cheerfulness that seems to emanate from Reichenbach’s discovery has for a short time made him forget his dejection.

“So, you want to leave,” says Reichenbach reproachfully, “just now, when such great things are happening here? I won’t hold you back, of course, but I would have thought…”

“I must go to Brünn and Salzburg. I’ve been invited to demonstrate my gas microscope. I haven’t given up on it either; I’m working on improving it and want to have new lenses made. I don’t know how long I’ll be away.”

“Travel with God!” says Reichenbach curtly and turns away, as if dismissing a renegade and traitor.

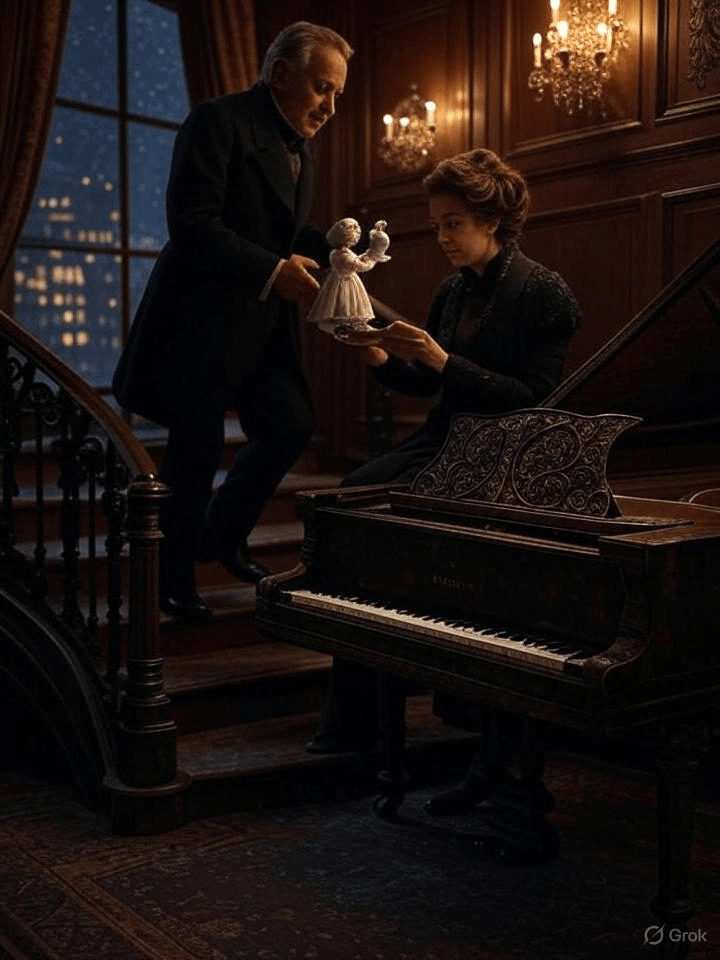

Karl Schuh slowly descends the stairs to the music room. Ottane sits at the piano; one hand rests on the keys, the other hangs limply down; her face shows a glow and an inward listening.

“Where is Hermine?” asks Schuh.

Ottane returns from afar. “I believe Hermine is already back at her treatise on the thylli.”

“I must leave tomorrow and won’t be back for a while.”

“Yes, why? You want to leave? Must it be? You should know that the music lessons with you are Hermine’s only joy.”

“Are they? I always thought Hermine’s only joy was the thylli and the like.”

“What’s wrong with you? Why do you talk like that? What have you suddenly got against Hermine?”

Karl Schuh takes a nodding porcelain Chinese figure from the dressing table, turns it over, looks at it from underneath, and sets it back down.

“And why do you only now say you have to leave?” Ottane continues. “You haven’t mentioned a word about it until today. That’s a fine surprise. Hermine will be quite astonished.”

Ottane looks up, and Schuh realizes she wants to fetch Hermine. This wretched porcelain Chinese won’t stop nodding, and Schuh stops the annoying wobbling with his finger. “No, please, don’t fetch Hermine.”

“Don’t you want to say goodbye to her?”

“No, I don’t want to say goodbye to her. You will convey my greetings to her.”

It’s all so strange and incomprehensible, but suddenly it occurs to Ottane what Max Heiland had said about Hermine and Schuh. A suspicion, so remote and questionable, that it had completely slipped from Ottane’s memory. It’s perhaps also true that she, entirely absorbed in herself, hadn’t paid attention to anything else.

“Yes, if that’s it…” says Ottane anxiously, and suddenly she feels utterly disloyal and bad.

Schuh lowers his head; not a trace remains of his radiant mood, his boyish laughter. It’s almost unfathomable that he can stand there so serious and dejected. “Yes, you must see that. What am I supposed to do here? I am, after all, a decent person.”

Ottane’s breath catches for a moment, as if she had received a harsh blow.

“And your father wouldn’t want it. I think I know him well enough. He became a Freiherr, and if he’s to give Hermine to someone, it must be someone entirely different, not just some Herr Karl Schuh.”

He’s probably right about that, thinks Ottane; the father has his peculiarities. And when he’s not in a good mood, he puts Schuh down, speaks contemptuously of him, calls him a windbag, a drifter, and a schemer.

“But worse still,” says Schuh again, “is that Hermine herself doesn’t want it. If it were only the father—his authority doesn’t extend to dictating Hermine’s life. But Hermine herself probably has no idea.”

“I don’t know,” Ottane hesitates guiltily; she’s ashamed to know so little about her sister and not to have cared for her.

“You see, and that’s why I can’t come to your house anymore. I’m not really traveling, but I won’t come back. Should Hermine eventually notice and then let me know it’d be better if I stayed away? I don’t want it to come to that.”

“What should I tell Hermine now?” asks Ottane quietly.

“You should give her this letter. She has a right to know how things stand. Give her this letter.”

“Does anyone else know about it?” Ottane feels compelled to ask.

“I’ve spoken with Reinhold about it. And now you know. And through the letter, Hermine will know. No one else.”

“I think the father is coming,” whispers Ottane. Somewhere a door opens—yes, those are the father’s steps in the next room.

It’s a hasty farewell; Karl Schuh doesn’t want to meet Reichenbach again now, having lost all composure and unable to control himself. He must leave quickly; the Freiherr should least of all learn how things stand with him.

“Wasn’t that Schuh who just left?” asks Reichenbach. “What did he want again? He’s probably off on another art trip.”

Ottane realizes she still holds Schuh’s letter in her hand. She’s still dazed and unpracticed in secrecy, and so she makes the clumsiest move possible—she tries to slip the letter into her pocket unnoticed.

But Reichenbach did not miss the suspicious movement. “What kind of letter is that?” he asks.

“A letter?” Ottane feigns with even more suspicious nonchalance.

Reichenbach doesn’t waste much time; his mood is steeped in vinegar and gall, some of what Schuh objected to is churning within him. He approaches Ottane and takes the letter from her pocket.

“Father, it’s a letter for Hermine,” Ottane protests indignantly.

“I can see that.”

“You won’t take this letter away from Hermine.”

“I wish to know what Herr Schuh has to write to my daughter.”

But Ottane is outraged—outraged for her sister’s sake, no, perhaps even for the sake of justice and freedom. “Father… you have no right to open someone else’s letters; I find that…”

“I find… I find…” snorts Reichenbach grimly, “I find that I certainly have the right to know what’s going on in my house. I find that I don’t need to tolerate any secrets.”

For a moment, Ottane considers, come what may, snatching the letter from her father, but it’s too late—the Freiherr has already broken the seal. “Oh yes,” he says, pressing his lips together and then parting them with a snapping sound, “mm yes… so that’s it…” and as his eyes glide over the lines, he underscores Schuh’s words with various exclamations: “Now I understand… indeed… so Reinhold has known about it for some time… very nice!… so that’s why…”

Then he folds the letter together, and as Ottane reaches for it, he slips it into his breast pocket. “This is a whole conspiracy against me; Reinhold knows about it, this man didn’t think to inform me at once, and you certainly wouldn’t have told me either…”

Ottane gathers all her courage for one more attack: “Schuh acted entirely honestly. And you surely wouldn’t want to lay hands on someone else’s property.”

“What I want or don’t want, I decide myself. And I want Hermine not to receive this letter. And if it’s true that Schuh hasn’t declared himself to Hermine, then she shouldn’t learn anything about it. I derive great joy from my children, I must say. And this Schuh! Writes letters to my daughter behind my back and intends to stay away from my house. Doesn’t consider that people will ask: yes, what’s wrong with Schuh, why doesn’t he come to Freiherr von Reichenbach anymore? There must have been something! That people will poke around and gossip, of course, you don’t think of that.”

“You can’t expect him to come when he loves Hermine and sees no chance to win her, and when he also doesn’t want to deceive you.”

“He should control himself if he’s a man,” Reichenbach shouts, “and he shouldn’t bring my house into disrepute. But I will restore order, depend on it.”

Hermine will not receive this letter, and you will keep silent about it and everything Schuh told you—take my advice.”

Reichenbach leaves, slamming the doors of the music room and the next room forcefully behind him, unaware that something far more significant has shattered and fallen away than just the plaster around a doorframe.

Leave a comment