OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

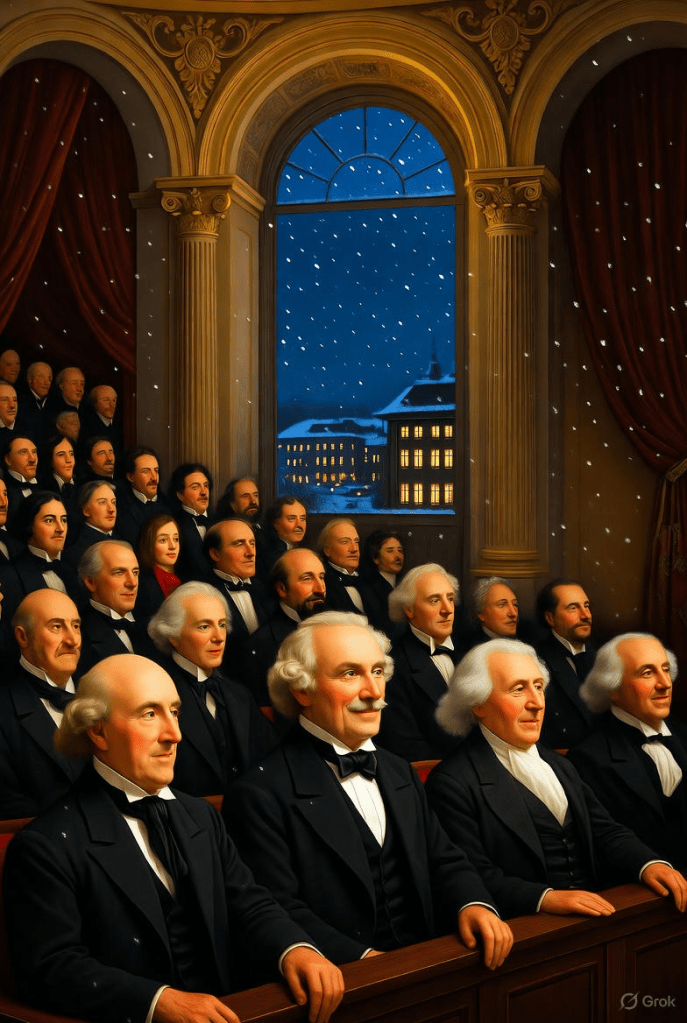

In the grand assembly hall of the Academy of Sciences, a distinguished audience is gathered today. The great luminaries of science are all present; they don’t want to miss this occasion—not always do they come with such eager anticipation as today, when Freiherr von Reichenbach is to deliver a lecture on his Od. Often enough, it’s merely a tedious duty; they attend serious and beneficial discussions but yawn in advance. Today, however, they smile, knowing it will be entertaining. Freiherr von Reichenbach is in everyone’s people’s mouths—the whole city is talking about him, less for his Od and more for other matters.

“Say, have you also received that lithographed letter he sent to all his friends?”

“A kind of wanted poster, after his daughter and a certain Karl Schuh.”

“A public accusation!”

“But that’s the Schuh with the light paintings. A talented man, he works in a chemical factory. Certainly not the blackguard the Freiherr paints him as.”

“Say, can you understand the man? Normally, one washes dirty laundry quietly at home, but Reichenbach airs it for all the world to see.”

“A passionate nature! A man who can’t bear not getting his way.”

“Just like with his Od.”

“But one doesn’t accuse one’s daughter of consorting with an adventurer in a public circular letter.”

“And that she nearly emptied all the chests when she left his house and left keys to half-empty rooms behind.”

“That’s not true. Reichenbach writes of two loads she took. I know her brother; he told me it was no more than two hand carts with her clothes and linens.”

“I can only think he’s upset because he’s not making progress with his Od, and now his domestic troubles have completely unhinged him.”

And then, after everything has been thoroughly discussed at length, Reichenbach arrives. He’s a bit late, giving the luminaries of science time to finish their gossip—the gossip he himself turned into a public matter to show he has nothing to hide. After the self-destruction of recent weeks, he’s in a festive mood today. This is the day of his triumph; he will compel the men of science with the force of his words and the logic of facts to acknowledge his research results and cheer for him. Against the dark backdrop of his personal distress, his fame as a discoverer will shine all the brighter.

At the door, Professor Schrötter, the Academy’s general secretary, greets him.

“What do you say to Liebig?” he asks first thing.

So they already know—Reichenbach dislikes being reminded of it; yes, malice always spreads with the speed of wind, while praise and recognition lag far behind.

It’s unpleasant to be reminded of this setback at the outset; the wound still stings. But Reichenbach merely smiles and says offhandedly, “What can you do? He wanted to make a splash with his inaugural lecture at Munich University and chose my Od as a sacrificial lamb. Scholars often slaughter their best friends to get themselves talked about.”

“Liebig was entirely for you at first. He published your papers in his Annals. How do you explain the turnaround?”

“How do I explain it?” snorts Reichenbach contemptuously. “Some gentlemen visited me, on their way to the naturalists’ convention in Wiesbaden. They also chose to learn about my experiments. I led them into the darkroom, but they saw no Od light. None of them were sensitive, and besides, they were too impatient to wait the necessary time. Then they went to Liebig in Munich and mocked the Od and me. It’s always easy to laugh when you don’t understand something. But it seems to have made an impression on Liebig.”

“Still,” hesitates Schrötter, “his attack has been noticed.”

Reichenbach tightens his resolve: “By the way, I was in Karlsbad with Berzelius, who puts Liebig in his pocket, and Berzelius is entirely on my side.”

They take their seats, and Hofrat Rokitansky, the vice president, opens the proceedings. A protocol is read, a foundation charter is announced, and several new decrees follow, though the assembly pays only moderate attention. Only when Reichenbach steps to the lectern do heads lift and expressions sharpen.

Reichenbach’s gaze surveys the densely packed audience. There they sit below—indifferent, malicious, envious, curious—come to see how he will hold up. He knows they’re all thinking of the scandal in his house, of Liebig’s defection. But his conviction stands like a steel pillar within him; he is bathed in the light of holiest certainty. Today, he will rise and crush all resistance. He has even summoned opposition, awakened enmities, so that his elevation will shine all the brighter.

Then Reichenbach begins to speak. He starts with an overview of his experiments; he has conducted thousands of trials, identified one hundred and sixty sensitives—men and women of all classes and ages. He has examined animal bodies and supposedly dead matter.

Reichenbach overlooks a faint cough at this challenge to a widely accepted view. Is matter not dead, then? He straightens: “The result of these investigations is the unerring certainty of a force permeating the entire universe, which I have named Od, derived from the Sanskrit root Va, meaning ‘to blow’ or ‘to waft,’ just as the same root becomes Wudan, Wotan, Odin in Old Germanic, signifying the air god, the wafter. Truly, this dynamis acts throughout the cosmos, wafting through the greatest and the smallest. Heavenly bodies, humans, animals, plants, stones—all emit Od, all are permeated by Od; Od is the life principle of the animate and inanimate world.”

The tufts of hair on either side of his forehead blaze—not in anger this time, but in enthusiasm. They rise and seem to spark with crackling energy. Some think to themselves that whatever may be undesirable, petty, or unpleasant about Reichenbach the man, now, as he stands before his audience, swept away by his idea, one cannot help but find him grand and admirable—even if his worldview rests on delusion and error. Some say this to themselves, but far more find the fire of his rapture out of place here, where facts—sober, research-based facts—usually hold sway. They are suspicious of a lecture with so much passion.

Perhaps Reichenbach senses this, for he now reins in his fervor. He is, first and foremost, a physicist and chemist, isn’t he? And so he intends to speak only as a physicist and chemist. Now he constructs his system before the audience—the convictions drawn from endless experimental series, meticulously recorded in his diaries and soon to be accessible to the public in his comprehensive work, The Sensitive Human. He speaks of the odic polarity and the odic dynamics of the human body, of odic transitional states, of crystals, magnets, odic emotional and visual phenomena, of odic manifestations of smell, taste, and hearing, of conductivity, of Od linked with living organisms—the Biod, of the Od active in the sun—the Heliod…

It’s a wealth of connections, insights, and assertions in which Reichenbach is entirely at home, but which bewilder and overwhelm his listeners.

A quiet restlessness in the hall gradually penetrates his awareness; he glances at the clock, almost startled. He has spoken for two hours; it’s time to conclude. He clenches his fists, as if to hammer his final sentences with all his might into their heads. “You see, gentlemen, the polar oppositions of that natural force which I call Od. On the negative side of Od are life, movement, lightness, and volatility—the spiritual principle; on the positive side are death, stillness, weight, and immobility—the material principle. The right side of the human body is odically negative. Why does man predominantly use his right hand? Why does one escort a lady on the right arm? Why is someone to be honored placed at one’s right? From the unconscious recognition that the right side signifies odic life and spirit. Heavenly bodies, humans, animals, plants, and stones are bearers of Od. What mysteries are revealed to us! Odic radiations from the stars—do they not explain the ancient riddles of astrology, the fate-determining influences of the stars? The Earth itself is odically charged; its North Pole emits reddish light, its South Pole bluish light, and perhaps the auroras are nothing but immense odic discharges of the Earth. Od also provides the key to the mystery of the divining rod. Moving water acts odically, and the sensitive, holding the divining rod, senses hidden springs beneath the Earth through his receptivity to Od. You may think what you will, but the facts of distant influence, remote viewing, and premonition cannot be denied in many cases. Allow me to cite an old proverb: ‘Speak of the devil, and he appears!’ Following a sudden inspiration, you speak of a man you haven’t thought of for years thought of for years. And lo, in the next moment, he turns the corner. It’s his Od radiations that preceded him and awakened the thought of him before you knew of his physical proximity. The unaccountable affections and aversions between people stem from sympathy or opposition of their odic personalities. Yes, I would venture to say that even the manifestations revealed to spiritualists—the so-called spirit appearances—are based on facts of an odic nature.”

A voice interrupts him here, coming from one of the back rows. It says loudly and clearly, “Wizard of Kobenzl!” Though such interruptions are uncommon at this venue, the heckler receives no reprimand; instead, a wave of approving smiles ripples through the rows of faces, followed by a rustling of agreement and nudges.

Reichenbach straightens, trying to fix his gaze on the malicious interrupter, but he can’t pinpoint the source of the shout. “The presence of Od in a body determines its stereoplastic, body-forming power, and thus I believe that even in seemingly dead stone, forces of immense significance may be bound. It is Od that governs the atoms and, within atoms, the arrangement of matter, its transformation, bonding, and splitting. It is Od on which our entire chemistry rests, and perhaps with Od we have reached the hypothetical ether. Odic radiations permeate the entire universe, and I dare to predict that a time is near when all life will be seen as an effect of such radiations.”

Reichenbach has finished; he falls silent, exhausted, but still stands erect, having hurled his fiery thoughts out. He awaits the ignition of a flame in the minds seized by his fire, the applause of those swept away by his boldness.

A shuffle of feet, coughs, the scraping of chairs, a wave of heads from the distinguished assembly below him. He shouldn’t have spoken of astrology, remote viewing, spirit appearances, divining rods, and other spawn of superstition before this esteemed gathering. What is one to say to such nonsense? How should one respond? How dare he present this to the luminaries of science, bearers of enlightenment in this thankfully advanced century?

Reichenbach waits, but the applause doesn’t come. He doesn’t fully grasp it—have they not recognized the overwhelming significance of his discovery? Don’t they see that it reduces all phenomena of nature and life to a single law, a fundamental force?

Someone rises to speak—Professor Schrötter, Reichenbach’s friend. Reichenbach breathes a sigh of relief; a friend, surely he will now make the matter palatable to the assembly. Perhaps he knows best how to address these thickheads. Maybe it was too much fireworks at once for more cautious minds.

Professor Schrötter pushes back the tails of his coat with one arm, as he’s wont to do at the lectern, and raises the other hand in a gesture of professorial insistence. He begins by saying it’s unnecessary to speak of the undeniable contributions of Freiherr von Reichenbach to science in this assembly. With small hand movements, he tosses out names like Paraffin, Creosote, Zaffar, Eupion, Kapnomor into the hall, glances toward the ceiling, traces a semicircle with his hand, and mentions Reichenbach’s research in meteoritics, eliciting approving nods from the scholarly society.