Homo Sapiens: Under Way by Stanislaw Przybyszewski and translated by Joe E Bandel

VI.

The next day was a wonderful morning. Over the whole area lay the dew-glistening sunshine, and from the fields rose silvery mists in wisps.

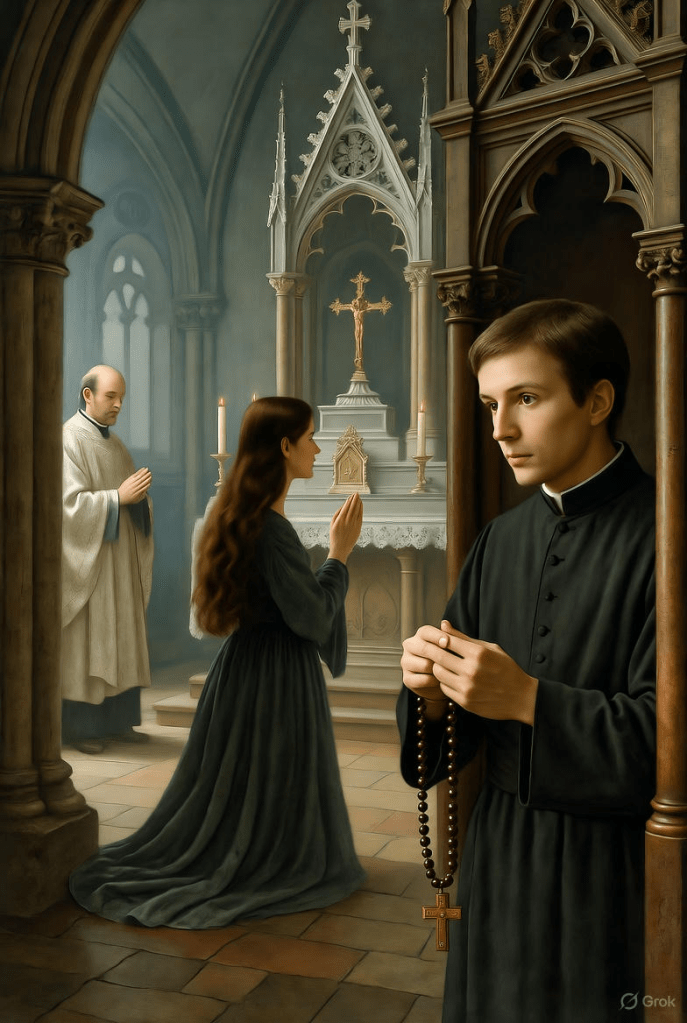

Marit went to early Mass. She was very pale, but from the exhausted, grief-stricken child’s face spoke an otherworldly calm.

She walked, rosary in hands, and implored the Holy Spirit for the grace of enlightenment.

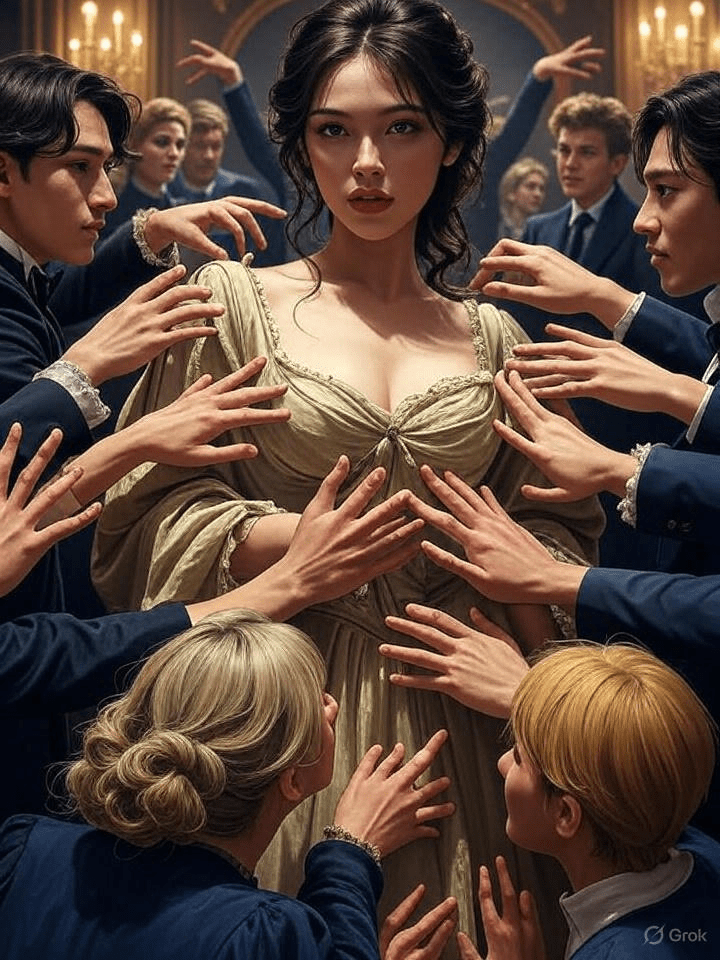

When she entered the monastery church, the priest had just begun the holy office of Mass in a side chapel. Marit knelt before the high altar and prayed a fervent prayer. To the side, in a confessional, sat a young priest who watched her curiously. He too held a rosary in his hands, and his fingers mechanically slid from one bead to the next.

Marit stood and approached the confessional. The confession lasted a long time.

Suddenly, Marit rose, walked with shy steps to a pew under the organ loft, sat down, hid her face in her hands, and began to cry.

The shameless man! To ask her such things! No, she didn’t want to think about it. Her head was completely confused. She hadn’t understood the priest. It was impossible: a servant of God couldn’t ask such questions.

Dark shame-red rose in her face.

The crude son of a farmhand! Yes, she knew, he was a peasant. Erik was right to be so furious against the priests; they all came from farmhands.

But all people sin. A priest can err. He probably meant well; he wanted to be conscientious.

But Marit’s innermost soul burned with shame and indignation. She cried. She felt trampled like a worm. Not God, not Mary, not the priest; no one, no one wanted to help her. Everyone had

abandoned her! Oh God, God, all-knowing, merciful God! How unhappy, how wretched, how sick she was.

The altar boy rang three times.

No, now she couldn’t take the body of Christ, not now; she didn’t want to.

She looked around, distraught.

Church? No, this church, this smell of sweat and bad food. Falk was right: no one could stand it in there.

Marit left the church.

She stood indecisively.

Could she go to Mrs. Falk? No, impossible, how would that look. Oh, she had noticed the sharp eyes that Mrs. Falk directed at her and Erik.

And Erik is coming out today; yes, absolutely; he’s so good. Now she would listen to him calmly; yes, he was right. The priests are sons of farmhands; they become priests only to have good and easier bread. Hadn’t Falk said it was statistically proven: only farmhands and peasants let their sons become priests.

And suddenly she remembered word for word what Erik had told her a year ago.

He had a relative who had to feed seven children and her old mother. The husband was a mason, fell from the ladder and died. It was when Erik was still in gymnasium.

And now Marit clearly heard Falk’s voice:

I entered a small, poor room. Did I want to see the dead woman? No, I don’t like seeing dead people; it’s unpleasant. She should go to the priest, tell him her situation, then he would attend the funeral for free. Yes. So she went to the priest. But the priest—what did he say?

Back then she hadn’t wanted to believe it; now she knew it had been truth. No, Erik didn’t lie.

Behind the monastery church flowed a narrow strip of water, a small tributary spanned by a bridge.

Marit stopped on the bridge and looked into the water. What had the priest said?

Again, she clearly heard Falk’s mocking, cynical voice: Give me three thalers, and I’ll bury the body; otherwise, he can be buried without a priest, that costs much less.

Marit involuntarily thought of the confessional. A shiver of disgust shook her.

She walked on thoughtlessly.

Oh, if he would come now! He usually took walks early in the morning. If she met him now…

Her heart began to beat violently.

Yes, now she would listen to him calmly, let him say everything, ask him more questions.

But she waited in vain; the whole day in vain. Falk didn’t come. She had already walked through the garden a hundred times and peered at the country road, but no person was to be seen; only now and then a dust cloud rose, flew closer, and then she recognized a cart from the neighboring village.

Tomorrow he will come, she thought, and undressed. She hadn’t lit a light, for she was afraid of the image of the holy Virgin; she didn’t want to see it.

She stood indecisively before the bed. Pray?

She asked herself once more: Pray?

The ridiculous lust for happiness, the shameless lust for happiness, mocked in her ears.

She got into bed with listening fear.

Would the all-knowing God punish her on the spot? She lay listening, waiting.

No, nothing…

The clock ticked and tore the deep silence.

She was very tired and already half-asleep. Her brain was paralyzed. Only once more did the question dawn in her: whether he would come tomorrow.

And if he has left?! No—no. She was completely sure, she knew: now that she was his, completely his, now that she lived with his spirit, now he hadn’t left.

Strange, how sure she knew that…

But she also waited for Falk in vain the whole following day, the whole endless, terrible day.

Could she endure this unbearable longing much longer? Involuntarily, she looked in the mirror.

Her face looked completely destroyed. The eyes glowed from sleepless nights and were blue-ringed. Feverish spots burned on her cheeks.

A deep pity for herself seized her.

How could he torment her so inhumanely; why punish her so terribly?

She felt like a child unjustly beaten.

She tried to think, but she couldn’t gather her thoughts, everything whirled confusedly in her head.

What was happening to her? She clearly heard continually single words, single torn sentences from his speeches. They gradually became like a great creeper that spread over the entire ground of her soul, overgrew everything, and climbed higher and higher with a thousand tendrils, up into her head.

She was so spun into this rampant net of strong creepers that she felt locked in a cage whose walls grew ever narrower. Everywhere the trembling cage bars, one next to the other, ever more pressing, from four sides.

God, God, what was happening in her?!

Falk’s great spirit: piece by piece it passed into her. She thought with his words, with the same tone, the same hoarse half-laugh that was in his speech.

She resisted, she fought with all her strength; but suddenly a grinning thought overpowered her.

It was as if he had brutally stripped all the holy, all the beautiful around her; huh, this hideous nakedness!

Yesterday in church: how was it that she suddenly discovered behind the glory of the divine service the brutal face that so disgustingly reminded her of a farmhand’s face?

And now, now: what was it, for heaven’s sake?

She didn’t want to see it, but again and again she had to stare at it.

Yes, how was it? The whole expression of the holy, supernatural suddenly vanished from the image of the Byzantine Madonna, and Marit stared into the stupid laugh of a childishly painted doll.

No, how ridiculous the picture was!

“Christ was the finest, noblest man in world history—yes, man, my Fräulein; don’t be so outraged, but it is so.”

And now a swarm of arguments, syllogisms, blasphemies hastened through her head.

No, she couldn’t think of it anymore.

And now she sat and sat in a dull stupor. The whole world had abandoned her. Him too…

When she came down to the dining room, it was already evening.

“Marit, I have to go to Mama at the spa; her condition has worsened. It probably won’t be dangerous, but I’m still worried.”

Herr Kauer took a slice of bread and carefully spread butter on it.

Mama? Mama? Yes. She had forgotten everything; everything was indifferent to her. She felt over her a dull, lurking doom, a giant thundercloud that wanted to bury a whole world.

“Yes, and then the district commissioner has invited us for tomorrow evening.” Marit flinched joyfully. There she would see Falk. He was good friends with the district commissioner.

“Yes, Papa, yes; I would very much like to go to the district commissioner’s. Yes, Papa, let’s go.”

But Kauer wanted to travel early in the morning. Marit didn’t stop begging.

She never went anywhere; she would so like to see lots of people again.

Kauer loved his daughter; he couldn’t refuse her anything.

“Well, then I can take the night train. But then you have to go home alone.”

“That’s not the first time. She’s a grown girl.”

Kauer ate and thought.

“Why doesn’t Falk come anymore? I really long for the fellow. Yes, a strange man. The whole town is in

turmoil over him. But he really does crazy things. Yesterday he meets his mother as she’s driving home a pig she bought at the market; she couldn’t get a porter. What does my Falk do? He takes the pig by the rope, drives it through the whole town, from street to street, his mother behind him—yes, and when people stare at him all dumbfounded, he sticks a monocle in his eye and drives the pig with majesty and dignity…”

Marit laughed.

“Ha, ha, ha—Herr Kauer couldn’t stop—”a pig driver with a monocle! Wonderful… And in the evening, well: you know that goes beyond measure: he offered the high school director slaps in the face.”

“Why?”

“Yes, I don’t know; but it’s really a fact. But imagine, Marit: to the director! Yes, yes, he’s a strange man. But the strangest thing is that you still have to love him. It’s a shame about the man, hm: they say he’s drinking terribly these days. It would really be a shame if he ruined himself through drinking.”

Marit listened up.

“Does he really drink so much now?” “Yes, they say.”

Marit thought of his words: he only drank when he felt unhappy. And Father sometimes drank too…—

She felt a strange joy.

So it wasn’t indifferent to him… Tomorrow, tomorrow she would see him…