The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

With that, he stood up, told me to eat the meal he had

ordered, a chocolate pudding with jams, and then to go to sleep.

I saw him slowly leave the room, with a friendly face,

holding a stick with a golden pomegranate daintily pressed to

his chin. After a few days I got up, and this all the more gladly,

as in the last days various noises, coming from the outside,

such as shouts, whistles and voices, had disturbed the silence of

my room.

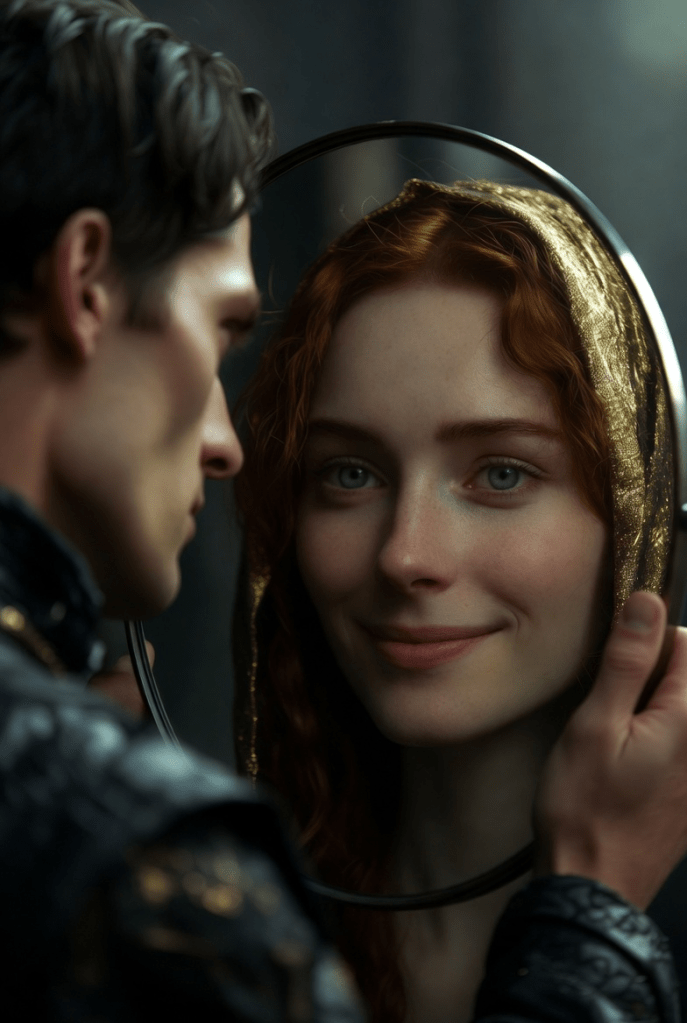

With the help of the servant of the inn, I dressed and had

my hair done, during which I perceived that the silver hoop of

old age had fully descended on my head during my illness. The

good-natured servant told me many horror stories from France,

where blood flowed in streams and a human life was not worth

three pennies. The plague of the frenzy for freedom was

already spreading, and even in this otherwise calm and quiet

old-fashioned little town, all kinds of disgusting and unpleasant

things had happened in the last few days, which had been of

the journeymen and the erection of a liberty tree. However, the

city council had wisely submitted a petition to the highest

authority for cavalry and a battalion of infantry, which, as the

princely book keeper Gailer had informed him confidentially,

should be complied with as soon as possible.

When I had finished, I slowly descended to the dining

room and found there at the common table, to my great delight,

Doctor Schlurich, who immediately left his place and sat down

next to me.

We naturally got into a conversation about the exciting

events in the city, which had become like a faint flame to the

immense blaze of purple in France, but still seemed worthy of

attention. I said that I felt a great desire to go to the city of

Paris, to study the immense changes there at close quarters and

observe them. I could not conceal from him that the movement

that had begun there was of great interest to me, was

meaningful for the whole of mankind and downright promising.

Doctor Schlurich looked at me with a very thoughtful

look and said that he was somewhat surprised to see a

nobleman from an old and famous lineage see anything but

cheap disgust in these events. The profound upheaval which

was only in its infancy could not possibly be welcomed by a

caste whose privileged existence rests on an artificial nimbus

and a carefully sanctified tradition. He asked me, however, not

to misunderstand him. Because his initial astonishment about

my behavior was a thoroughly joyful one.

I replied that I had suffered a self-inflicted humiliation in

my youth that had given me the opportunity to go to school

among people of the lowest classes, which, whether it was

good or bad, had given me the opportunity as a student of

freeing myself from all arrogance and conceit of status. In

addition, I had gained the valuable awareness that the so-called

differences in standing were created by artificially erected and

easily removable barriers, which had arisen and were

maintained, to deprive the children of the poor from any better

education and the cultivation of their noble feelings, which

later on resulted in their crudeness and ignorance. The

undeniable merits of the society to which the nobility and the

refined bourgeoisie enjoyed, were only the result of a carefully

conducted education. If this could only once be shared not just

with the privileged classes, but with all members of the human

race, humanity would not only protect itself with the noblest

weapon, but it would also bring an immeasurable abundance of

talents and abilities into a new light that has never existed

before. Indeed those places, where they shyly blossom in spite

of all the pressure, and are suppressed as dangerous to the state

without any knowledge.

“You are a nobleman in the inner sense of the word,” said

the doctor and bowed.

I felt the blush of shame rise to my face, and silently I

thought of many things in my life, which were of an ugly

nature and would always remain as stains on me.

“However, cher haran,” the doctor continued, “I don’t

know whether, if you were to ask for my advice, I would advise

you, to witness the great upheaval in the immediate vicinity,

that is to say, in Paris. Consider:

If one cleans a neglected place in his garden, in order to

grow useful and lovely plants, and removes the old stones and

debris, ugly worms, woodlice, centipedes and all kinds of nasty

creatures, which now crawl from their dark places, run around

and fall on each other in sudden greed. So it is also with those

social changes that are called revolutions. Until the noble core,

the light of freedom, shows itself, there is abominable work to

be done, which perhaps people can only see who look back

after many years, but to those who experience it, their souls are

filled with such horror that they no longer recognize anything

else, and even lose hope. Revolutions are filled with filth,

blood, shouting, evil deeds, wild development of the animal

instincts and base greed, and it takes a long time for the jet of

fire that shoots up to become pure and free of filthy cinders,

and the dominion of the senseless to move into the hands of

sensible men.”

A wild yelling and screaming outside the windows

interrupted him. In the dining room there was a hurried pushing

back of the chairs and jumping up. One saw people outside

walk by on the street, first individually, then dense masses, and

behind them came a closed united front of dragoons, which

struck with the flat of their swords and thus cleared the street.

All this passed quickly, the shouting and the clattering hoof

beats on the cobblestones disappeared, and in a few minutes

the street was quiet again, covered with lost hats, sticks and

other things.

“Our good Germans are slowly maturing,” Doctor

Schlurich returned back to the table. “And many a thing will

still pass over our people, until they are able to assert inner and

outer freedom, from which, by the way, even the French will

still be without. The merit, however, of having made a start

could be left to them, if one did not have to concede it from the

standpoint of higher justice from the English viewpoint.

Nevertheless, Herr Baron: The Germans will, after much

suffering and hardship be the chosen ones, from whom the

salvation of the world emanates. This is my belief.”

We were silent for a long time, and our conversation

turned to other things. I learned that Doctor Schlurich, born in

Köllen, had settled here, not so much to earn money, which in

his circumstances was not necessary, but in order to calmly

work on unknown phenomena of a psychical nature, with

whose research he was mainly concerned. Here he had made a

very special find. Namely, in a house of the city lived a

Demoiselle Köckering, who, in the company of various doctors

was often put into a magnetic sleep and in this state was asked

questions about the past and the future, as well as the most

diverse things to which she answered completely and correctly.

If I happened to be interested in such secrets of nature, which

only the unintelligent can connect with ghosts and devils, it

would be easy for him to introduce me there. Since the person

must be kept secret and lives from her art, it is, however,

customary to give a douceur in gold at the first entrance.

I was immediately ready to be led by him into the house,

and thanked him for his trust.

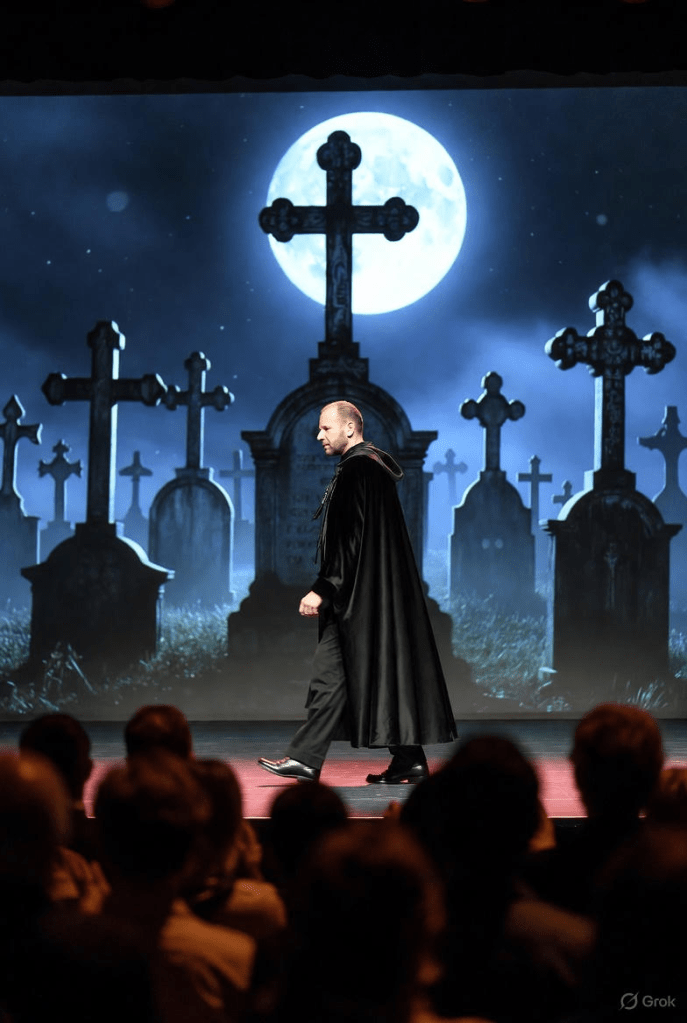

When it began to dawn, we went on our way.

A cool, damp wind was blowing from the Rhine. The wet

air penetrated chillingly through our coats. In several streets we

were stopped by patrols on horseback with loaded carbines, but

were allowed to pass as persons of distinction.

After some wandering we found the house “Zum

silbernen Schneck”, in which the demoiselle lived.

Only after knocking several times was the door opened to

us by a man, who was finally able to hide his hesitation for fear

of the craftsmen and ship’s servants, who, together with the evil

folk from the taverns, hooting “Ca ira” and hammering on the

gates, had raged in the alley a short while ago to get the

prostitutes living in the house next door and take them with

them. Soldiers would have quickly driven the screamers away

and then would themselves have gone through the door with

the red lantern.

We climbed the narrow staircase by the light of the

tallow candle that dripped between his fingers, and after a

special kind of knock, were led into a bright, octagonal

chamber, whose windows were tightly curtained. There was

nothing to be seen in it but an armchair upholstered in worn

brocade, next to which, on two small tables, burned many-

armed candlesticks, and in front of it a row of ordinary wooden

armchairs, on which some men sat waiting. They turned their

heads toward us. Both could be easily classed among the

scholars by their dress and the expression of their faces.

Doctor Schlurich and I approached the waiting people

and gave our names, which was answered in the same way.

“-especially the prophecies of the demoiselle should be

strictly examined,” one of the gentlemen, who was addressed

as “Spectability” continued his speech, which was interrupted

by our entrance.

“All the more so, as the man who pretends to put her into

a magnetic sleep collects one louisdor per person. My esteemed

colleague Professor Fulvius, who watched the demonstration

was not satisfied in all respects. Those bluish efflorescence’s

which you could observe perfectly, on the hands of

Emmerentia Gock in Ebersweiler, who is said to be possessed

by the devil, are completely absent, and everything that is

going on is just limited to some at times certainly astonishing

messages about the lives and fates of the people present.”

“Whereby it is respectfully to be noted,” said a small,

skinny man with a reddish wig in the highest falsetto “that the

prophesies of the woman, in so far as they refer to the future,

are completely worthless scientifically, because at present they

are unverifiable.”