The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

The way was not too long. I looked once more with the

old eyes that had seen so much during my existence, and

enjoyed the colorful multiplicity of the images that showed

themselves to me. I saw the butcher with a steaming, scalded

pig in a wooden trough, and the brass basins of a barber, which

rattled in the wind and rain and hung full of little drops. I took

the pitying look of two dark, beautiful girl’s eyes under a blue

and white bonnet, noticed a black dog that reminded me of

poor Diana, and smelled the strong, sour-tart smell of fresh tan,

coming from a tanner’s workshop. A steel blue fly with little

glass wings sat down on my knees and thus traveled quite a

distance without effort of its own. A bunch of funny screaming

spiders, uninvolved in humanity threw themselves like a brown

cloud over the smoking mountain of horse manure, which came

from one of the front wagons, and an ancient sycamore tree, all

hung with water beads, morosely and indifferently let us pass

by.

And then, with a jerk, all the wagons stopped.

We had arrived at the ugly square, where not long ago I

had spoken with the young officer about the French nation, and

my gaze fell on the gaunt reddish-brown scaffold that towered

high above our heads, with ghastly simplicity.

At that moment the wall of fog broke, and a pale ray of

sunlight fell with dull glint on the slanting knife high up under

the crossbeam.

“How soon all this will be over!” I thought, and

remembered so many moments of impatience and not being

able to wait, which lay far behind me in the old days.

We had to descend, and we were helped to do so. The

people did not shout. There was only that quiet murmur of a

thousand voices that betrayed the excitement of a great crowd.

No one shouted swear words at us, and many eyes looked

sympathetically. I had the feeling that with such a general

mood, the great killings would soon subside and finally stop

altogether. My knees were stiff from sitting and from the

morning chill. The distress of the body cramps set in once

again, and the right hip was very painful when walking.

I saw people appear on the platform, appearing to move.

The knife fell with a dull clang and was raised again. It was red.

Something struck the boards of the bloody scaffold.

The fear of the body almost gained the upper hand. A

thought pushed forward, gained space: To do something to save

myself, to scream, to beg, to break through the crowd, to break

the cords…

That’s when I saw him…

Huddled like a bat. Fangerle. He was sitting on a lantern

of the gallows, grimly distorting his wide mouth, the evil

yellow eyes directed at me, a red, Phrygian cap on his skull

instead of a big hat. His eyes were like two wasps that lived

and crawled around in the cavities of his head.

I closed my eyes. My will kept the upper hand.

“Return to the depths!” I said to myself.

When I looked again with all my strength, the apparition

had disappeared, the pole was empty.

A soldier grasped me almost timidly by the arm and

pushed me forward with gentle force. I saw how clotted, thick

blood flowed sluggishly down the boards of the scaffolding.

Before me the Marquis de Carmignac climbed the slippery

little stairs. Two men with naked arms grabbed him, strapped

him to the board, and tipped it over. The upper part of the wood,

which enclosed the neck, lowered. Whoosh…

A whistling sound came from his headless neck. The feet

with the buckled shoes, manly still in death, softly tapped the

ground, his body moved in the straps, as if he wanted to make

himself more comfortable. They loosened the damp leather,

rolled him aside; the golden pear rolled over the boards, a little

lid opened, brown snuff dusted out. Quickly a hand reached for

the shiny thing.

I was next, climbing the stairs.

A hand supported me kindly, saved me from a fall in a

moment of slipping. I looked into a serious, well-cut face. It

was Samson. He made a polite inviting hand gesture. Behind

him stood the red-bristled monster.

Images circled in my brain in a flash. The arm with the

executioner’s sword in the witch’s room of Krottenriede, the

box with the singing little bird, burning candles in a black room,

the glitter of Aglaja’s crown of death, the little dead man with

the hourglass and the scythe, as it tilted out of the old clock, the

Bavarian Haymon as an Amicist —Firm hands grabbed me by

the arm. Faces slid past me. I stood at the board. The warm

smell of blood rose to my nostrils, tickling and irritating in the

nose. Thin straps snaked around my upper body, my legs. I fell

forward — it creaked softly around me, – pain- my larynx hit a

semicircle.

I thought: Now the knife will cut through my throat,

sawdust will fill my eyes, my mouth —.

Wet wood descended on the back of my neck.

Isa Bektschi! Isa Bektschi!

With all my might I thought of the Ewli. I forced him to

me.

Close to mine I saw his face – his mouth, as if he wanted

to kiss me – kind, dark eyes, like two black suns. His gaze

enclosed me with infinite love and promise.

I thought nothing more. I saw only him – drank his looks,

absorbed his essence into me. Then dazzling, golden rays shot

out from his eyes, piercing me, consuming me in fiery embers –

in golden fire.

But still I saw that face, clearly, sharply, saw it growing

smaller and smaller – small as a dot and yet recognizable -.

I opened my mouth, felt woody, dry splinters, moist

chunks—.

Then night — hissing — sound — a painful tearing – a

thread cut in two —

I found myself outside my body. My body lay in its

brown, rumpled suit, without coat, with blood-soaked shirt

edge on the board of the guillotine. Despite the tight straps, my

upper body reared up a few times violently. Fountains of blood

rushed out of the two large neck veins.

The head lay pale, with wide-open eyes in the basket. Its

face smiled. All the people who were standing around the

scaffold looked on in silence. The board became empty. The

man who had called Astaroth and the fiery dragons was

dragged up the steps. He struggled with all his might, kicking

with his feet, snapping his teeth.

He did not want to – – All this was so indifferent for me. I

rose and floated away over the many heads, glided effortlessly,

and without finding any resistance, through the house walls and

window panes, driven by a force.

I had no eyes and saw everything. I heard. But I felt

nothing. I thought nothing either. I was consciousness itself.

Everything came to me, was immediately recognized.

Vibrations of many kinds trembled through me, without me

feeling pleasure or suffering. It was coldness, warmth, a sound,

light, phenomena for which there are no words in human

language, sensations when encountering beings, that remain

invisible and unknown to people.

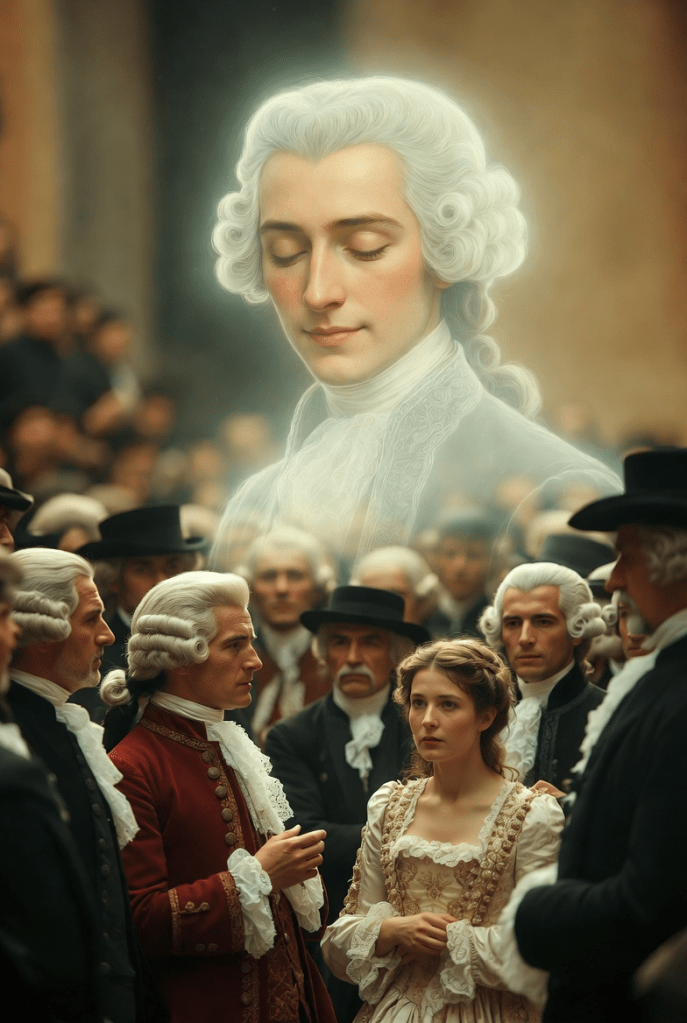

I was of a shape, if this is possible to say, like those

glassy-transparent bodies that glide past human eyes when they

look for a long time into the distant pure blue heavens.

Nevertheless I was not a body. I was also not nothing. I was a

soul, like many of those who floated in the world space. But I

had consciousness, I was mindful of my ego and I had a goal.

I was looking for a new house with those instruments of

the senses, which received from outside and could reflect from

the inner back to the outer: Could express thoughts as words. I

was looking for a human body. Inside me I carried the tiny

image of a noble, godlike face, the reflection of which I had

taken with me into infinity when I left the destroyed body.

From this image my consciousness extended along with the

ability to remember.

The will for re-embodiment was the only drive that

dominated me. According to inscrutable laws born of the

eternity of becoming and passing, I strove towards my goal,

devoid of all those feelings that can be called impatience,

expectation or hope. There was no time; there was no distance

and no obstacles.

Forces to which I surrendered of my own accord

willingly lifted me up, made me sink down, and made me to

fade away, to wander and to rest.

I was unmoved in my consciousness.

Everything was offered to me, nothing was hidden from

me, and nothing was veiled, neither in depths nor in heights.

The wind blew through me, the rain fell through me. I had

nothing of the properties that things in space possess. I was big

and small, inside and outside, far and near.

I saw sunsets in ocean wastelands, mountain hikers

crashed in crevasses of ice, blue flowers that slowly withered,

ghosts in waterfalls, beings that lived in crystals, red and

yellow sandstorms, and fermenting garbage, out of which new

creatures of the strangest kind sprang, dwarfs, who would have

appeared as stones to human eyes, winged creatures that rode

and roared, sleeping in beds, seeded with tiny goblins as with

vermin, people, from whom evil flowed like a poisonous breath.

I passed by all this.

There were animals in herds on vast steppes, animals in

the air, in holes in the ground, in the water. Small, crawling,

flying, running animals, animals of all kinds, covered with hair,

feathers, scales, bristles and plates, living animals. They

attracted me because they were alive. They begat young,

hatched them, reproduced thousands of times.

They attracted me strongly, because they had living

bodies, warm bodies. But I carried in me a human face and did

not follow those souls, that lurked waiting to enter into the egg

cell at the moment of conception.

I was only attracted to people. I was attracted to them by

a tremendous force.

It was good to be with people. I attached myself to them,

was with them, in them, slid through them and was a guest with

others. I lived with them. I saw them as one sees a region that

resembles the abandoned homeland. I have to use such

comparisons, although the truth is quite different.