Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

She spread her arms out wide reaching into the air. “Soldiers–”

she screamed. “I want an entire regiment.”

“Shame on you,” said Dr. Petersen. “Is that any way for a

prince’s bride to act?”

But his gaze lingered greedily on her firm breasts.

She laughed. “It doesn’t matter–prince or no prince! Anyone that

wants me can have me! My children are whore’s children whether

they be from beggar or from a prince.”

Her body became aroused and her breasts extended towards the

men. Hot lust radiated from her white flesh, lascivious blood streamed

through her blue veins–and her gaze, her quivering lips, her

demanding arms, her inviting legs, her hips, and her breasts screamed

out with wild desire, “Take me. Take me!”

She was not a prostitute any more–The last veils had been

removed and she stood there free of all fetters, the pure female, the

prototype, the ideal, from top to bottom.

“Oh, she is the one!” Frank Braun whispered. “Mother Earth–she

is Mother Earth–”

A sudden trembling came over her as her skin shivered. Her feet

dragged heavily as she staggered over to the sofa.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” she murmured.

“Everything is spinning!”

“You’re just a little tipsy,” said the attorney quickly. “Drink this

and then sleep it off.”

He put another full glass of cognac up to her mouth.

“Yes, I would like to sleep,” she stammered. “Will you sleep

with me, youngster?”

She threw herself down onto the sofa, stretched out both legs into

the air, laughed out lightly, then sobbed loudly and wept until she was

still. Then she turned onto her side and closed her eyes.

Frank Braun pushed a pillow under her head and covered her up.

He ordered coffee, went to the window and opened it wide but shut it

again a moment later as the early morning light broke in. He turned

around.

“Now gentlemen, are you satisfied with this object?”

Dr. Petersen looked at the prostitute with an admiring eye.

“I believe she will do very well,” he opinioned. “Look at her

hips, your Excellency, it’s like she is predestined for an impeccable

birth.”

The waiter came and brought coffee. Frank Braun commanded

him, “Telephone the nearest ambulance. We need a stretcher brought

in here for the lady. She has become very sick.”

The Privy Councilor looked at him in astonishment, “What was

that all about?”

“That is called–” laughed his nephew. “hitting the nail on the

head. It’s called that I am thinking for you and that I am more

intelligent than you are. Do you really think that when the girl is sober

again she would go one step with you? Even as long as I kept her

drunk with words and with wine I still needed to come up with

something new to keep her interest. She would run away from both of

you heroes at the nearest street corner in spite of all the money and all

the princes in the world!

That is why I had to take control. Dr. Petersen, when the

ambulance comes you will take the girl immediately to the train

station. If I’m not wrong the early train leaves at six o’clock, be on it.

You will take an entire cabin and put your patient into bed there. I

don’t think she will wake up, but if she does give her some more

cognac. You might add a couple drops of morphine as well. That way

you should be comfortably in Bonn by evening with your booty–

Telegraph ahead so the Privy Councilor’s carriage is waiting for you

at the train station. Put the girl inside and take her to your clinic–Once

she is there it will not be so easy for her to escape–You have your

ways of keeping her there I’m sure.”

“Forgive me, doctor.” The assistant doctor turned to him, “This

almost appears like a forcible kidnapping.”

“Yes it does,” nodded the attorney. “Salve your citizen’s

conscience with the knowledge that you have a contract!–Now don’t

talk about it, do it!–Do what you are told.”

Dr. Petersen turned to his chief, who was quiet and brooding in

the middle of the room and asked whether he could take first class,

which room at the clinic he should put the girl in, whether they

needed a special assistant and–

During all this Frank Braun stepped up to the sleeping prostitute.

“Beautiful girl,” he murmured. “Your locks creep like fiery

golden adders.”

He pulled a narrow golden ring from his finger, one with a little

pearl on it. Then he took her hand and placed it on her finger.

“Take this, Emmy Steenhop gave me this ring when I magically

poisoned her flowers. She was beautiful, strong, and like you, was a

remarkable prostitute!–Sleep child, dream of your prince and your

prince’s child!”

He bent over and kissed her lightly on the forehead–The

ambulance orderlies came with a stretcher. They took the sleeping

prostitute and carefully placed her on the stretcher, covered her with a

warm woolen blanket and carried her out. Like a corpse, thought

Frank Braun. Dr. Petersen excused himself and went after them.

Now the two of them were alone.

A few minutes went by and neither of them spoke. Then the

Privy Councilor spoke to his nephew.

“Thank you,” he said dryly.

“Don’t mention it,” replied his nephew. “I only did it because I

wanted to have a little fun and variety. I would be lying if I said I did

it for you.”

The Privy Councilor continued standing there right in front of

him, twiddling his thumbs.

“I thought as much. By the way, I will share something that you

might find interesting. As you were chatting about the prince’s child,

it occurred to me that when this child is born into the world I should

adopt it.”

He laughed, “You see, your story was not that far from the truth

and this little alraune creature already has the power to take things

from you even before it is conceived. I will name it as my heir. I’m

only telling you this now so you won’t have any illusions about

inheriting.”

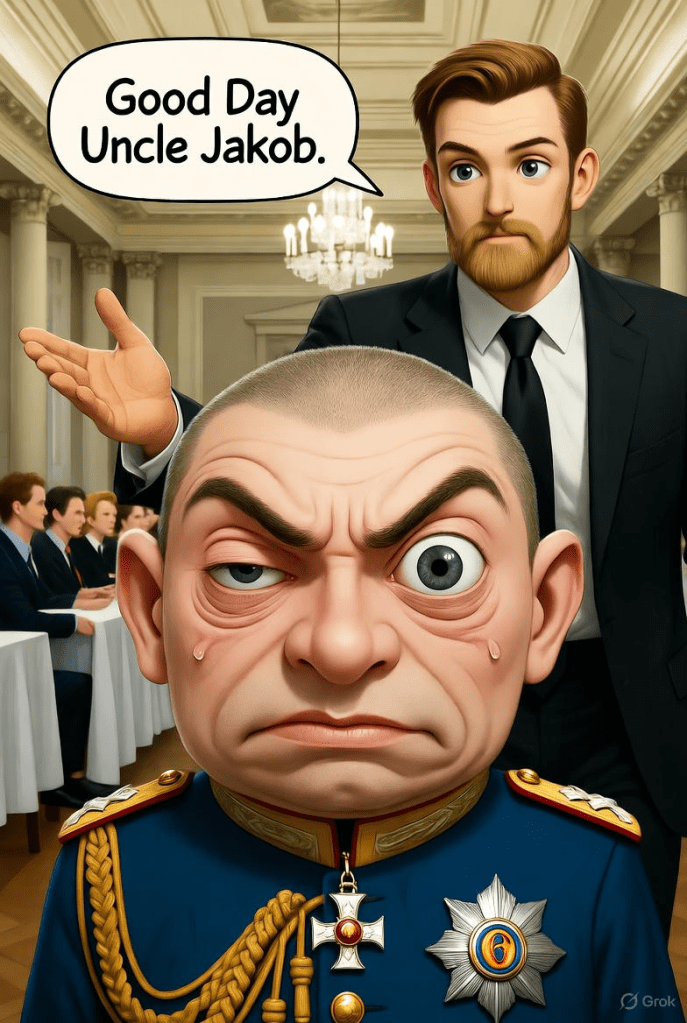

Frank Braun felt the cut. He looked his uncle straight in the eye.

“That’s just as well Uncle Jakob,” he said quietly. “You would

have disinherited me sooner or later anyway, wouldn’t you?”

The Privy Councilor held his gaze and didn’t answer. Then the

attorney continued.

“Now perhaps it would be best if we use this time to settle things

with each other–I have often angered you and disgusted you–For that,

you have disinherited me. We are quit.

But I gave you this idea and you have me to thank that it is now

possible. For that you owe me a little gratitude. I have debts–”

The professor listened, a quick grin spread over his face.

“How much?” he asked.

Frank Braun answered, “–Now it depends–twenty thousand

ought to cover it.”

He waited, but the Privy Councilor calmly let him wait.

“Well?” he asked impatiently.

Then the old man said, “Why do you say ‘well’? Do you

seriously believe that I will pay your debts for you?”

Frank Braun stared at him. Hot blood shot through his temples,

but he restrained himself.

“Uncle Jakob,” he said, and his voice shook. “I wouldn’t ask if I

didn’t need to. One of my debts is urgent, very urgent. It is a

gambling debt, on my honor.”

The professor shrugged his shoulders; “You shouldn’t have been

gambling.”

“I know that,” answered his nephew, exerting all of his nerves to

control himself. “Certainly, I shouldn’t have done it. But I did–and

now I must pay. There is something else–I can’t go to mother with

these things. You know as well as I do that she already does more for

me than she should–She just a while ago put all my affairs in order for

me–Now, because of that she’s sick–In short, I can’t go to her and I

won’t.”

The Privy Councilor laughed bittersweet, “I am very sorry for

your poor mother but it will not make me change my mind.”

“Uncle Jakob,” he cried into the cold sneering mask, beside

himself with emotion. “Uncle Jakob, you don’t know what you are

saying. I owe some fellow prisoners at the fortress a thousand and I

must pay them back by the end of the week. I have a few other

pathetic little debts to people that have loaned me money on my good

face. I can’t cheat them. I also pumped money out of the commander

so that I could travel here–”

“Him too!” the professor interrupted.

“Yes, him too!” he replied. “I lied to him, told him that you were

on your death bed and that I had to be near you in your final hours.

That’s why he gave me leave.”

The Privy Councilor wagged his head back and forth, “You told

him that?–You are a veritable genie at borrowing and swindling–But

now that must finally come to an end.”

“Blessed Virgin,” screamed the nephew. “Be reasonable Uncle

Jakob! I must have the money–I am lost if you don’t help me.”

Then the Privy Councilor said, “The difference doesn’t seem to

be that much to me. You are lost anyway. You will never be a decent

person.”

Frank Braun grabbed his head with both hands. “You tell me

this, uncle? You?”

“Certainly,” declared the professor. “What do you throw your

money away on?–It’s always foolish things.”

“That might well be, uncle,” he threw back. “But I have never

stuck money into foolish things the way you have!”

He screamed, and it seemed to him that he was swinging a riding

whip right into the middle of the old man’s ugly face. He felt the sting

of his words–but also felt how quickly they cut through without

resistance–like through foam, like through sticky slime–

Quietly, almost friendly, the Privy Councilor replied. “I see that

you are still very stupid my boy. Allow your old uncle to give you

some good advice. Perhaps it will be useful sometime in your life.

When you want something from people you must go after their

little weaknesses. Remember that. I needed you today. For that I

tolerated all the insults you threw at me–But you see how it worked.

Now I have what I wanted from you–Now it is different and you

come pleading to me. You never once thought it would go any other

way–Not when you were so useful to me. Oh no! But perhaps there is

something else you can do. Then you might be thankful for this good

advice.”