Homo Sapiens: Under Way by Stanislaw Przybyszewski and translated by Joe E Bandel

X.

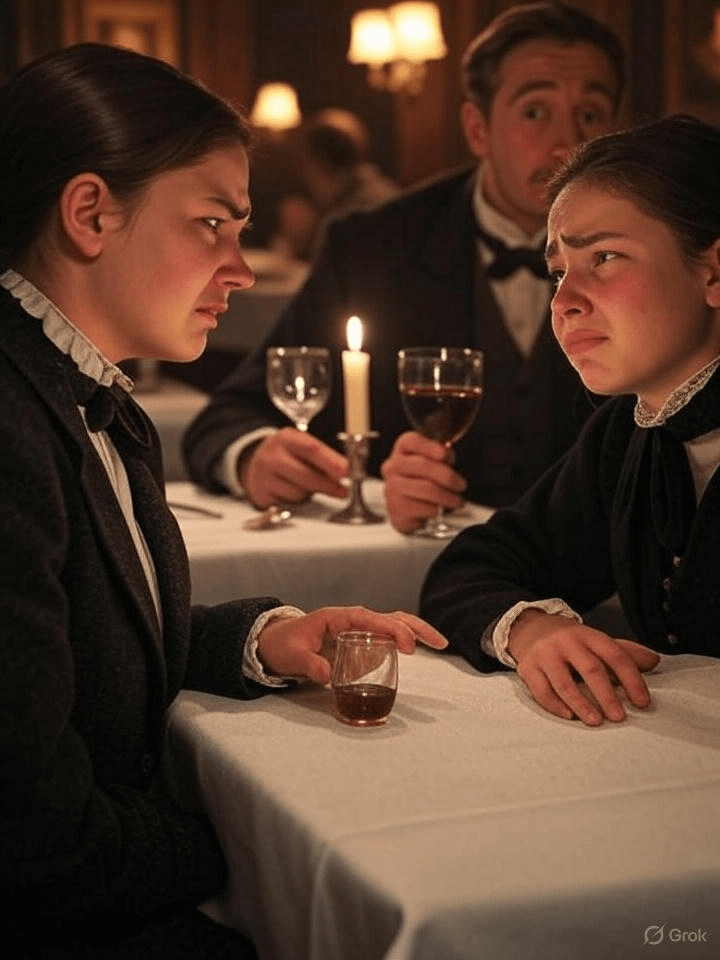

The restaurant was not closed despite the advanced hour; Flaum still had guests, and so they went in. The editor ordered wine.

“I’m very glad,” he said, “that we met again. It was terribly interesting how you performed at the district commissioner’s today. But—forgive me—you judge a bit too much in bulk and wholesale.”

“Yes indeed I did that. I often do. That’s self-evident. Every thing really has very many different sides, which—understand—not lie next to each other for convenient overview. No, sir, on the contrary. There are the most various illuminations. A thing is like a hectogon; only one surface gets full light there. And now look: the whole human judging rests on the fact that only this one surface is considered and perhaps still three or four that lie closest.”

Falk emptied the glass.

For his intellect there was no judging at all. He could say nothing certain about any thing. If he judged at all, it happened merely because he somehow had to communicate with people, and then he judged just like all other people, i.e. he proceeded from certain premises of which he knew that they counted as “given,” and drew the conclusions.

But for himself there were no premises and therefore also nothing “given”; he therefore asked the Herr Editor not to take his opinions as absolute.

The editor seemed not to understand that and drank to Falk for lack of an answer.

The young doctor listened curiously and drank very eagerly. Suddenly he got the desire to annoy the editor: Falk joked so excellently.

“What do you think, but in all seriousness, of a social future state?”

The editor winked his eyes; he noticed the malicious intent.

“What do I think of that?” said Falk. “Yes, I already developed at the district commissioner’s my opinion, which rests on ‘given’ valuations.”

“By the way, this whole state interests me only insofar as it—admittedly again only if the premises are correct, Herr Doctor—yes, only insofar as it can bring certain reforms in the field in which I am active.”

“Look, then for example the state will also create the social living conditions for artists, and then you can be convinced that many people who now à faute de mieux became artists because it is nowadays the easiest bread, will then rather become supervisory officials in some warehouse or otherwise make themselves somehow useful with four- to six-hour work time and social equality. Artists will be only those who must.”

The editor, who now scented joke behind every word of Falk’s, threw in irritably:

“You seem to hold artists in low esteem too?”

“No, really not, and precisely because there are almost no artists, or if there are any, they botch themselves immediately as soon as they have to bring their wares to market.”

“For me only he is an artist who is not otherwise able to create than under the unheard-of compulsion of a so-to-speak volcanic eruption of the soul; only he in whom everything that arises in the brain was previously glowing prepared and long, long collected in the warm depths of the unconscious—let us call it—that doesn’t write a word, not a syllable that is not like a twitching, soul-torn-out organ, filled with blood, streaming to the whole, hot, deep and uncanny, like life itself.”

“Well, such artists he probably never met?”

“Oh yes, yes! but only among the despised, the unknown, the hated and ridiculed, whom the mob declares idiots.”

Falk drank hastily.

“Yes indeed; and one of the greatest I saw go to ruin and perish. There was one, my schoolmate; he was the most beautiful

man I ever met. He was brutal and tender, fine and hard, he was granite and ebony, and always beautiful. Yes, he had the great, cruel love and the great contempt.”

Falk pondered.

“Yes, he was very strange. You know, that characterizes him: we once got the essay topic: how heroes are honored after death.

Do you know what he wrote? what would probably be the greatest honor for a hero?

“Well?”

“Yes, he wrote: the most beautiful honor he could imagine for a hero would be if a shepherd accidentally dug up the bones of the hero in question, then made a flute from the hollow bones and blew his praise on it.

Another time he wrote on the topic what benefit wars bring, that wars are a great boon for farmers, that they namely excellently manure the soil with the corpses of the fallen warriors; corpse manure is much better than superphosphate.

Yes, allow me, that is brutal; but brutal like nature itself. That is mockery; but the terrible mockery with which nature plays with us. Yes, sir: that is the sublime mocking seriousness of nature itself.”

The editor was silent, offended.

“Does Herr Falk want to joke with him? that really isn’t nice.”

“No, he doesn’t want that at all, he never joked with any person, least of all with the Herr Editor.”

“Yes, then they are only personal opinions that can apply only to one person.”

Falk felt a strange irritability that he couldn’t comprehend; but he controlled himself.

“Yes indeed; my opinions apply only to me. I am I and thus my own world.”

“Well, Herr Falk seems to have strangely high opinions of himself.”

“Yes, I have, and every person should have them. You know, there is a man in Dresden who calls himself Heinrich Pudor. In

general one holds him for a charlatan and he indeed makes himself talked about through strange quirks. For example, recently he demanded of the state attorneys that they prohibit the playing of Chopin’s music because it is arousing and sensual. But despite all the quirks there sticks in him yet a strange power.

Recently he held an exhibition of his own paintings in Munich. The paintings are supposed to be ridiculous and childish; I don’t know, I haven’t seen them. But for the exhibition he wrote a catalog in which it says: I am Heinrich Pudor! I am I! I am neither an artist nor a non-artist! I have no other attributes than only that I am I!

Look, that is well said.

No, you are mistaken, Herr Doctor: that is no excessively demanding significance. For as soon as I am human, I am precisely a significant, uncannily significant piece of nature. If I now say: Here are my paintings! however ridiculous they may be, but they are a piece of me! and presupposed that they are really generated from innermost compulsion: then they characterize me better than all good deeds I have done and will still do.

Here is a piece of my individuality; whoever is interested may look. I am I, and nothing is in me of which I need to be ashamed.”

“But that is absolute megalomania,” the doctor threw in.

“Absolutely not absolute and absolutely not relative! You as doctor should know that the so-called megalomania goes hand in hand with the loss of individuality. Only when the consciousness of my ownness is lost do I hold myself for Napoleon, Caesar etc. But even the strongest consciousness of my own I and its significance has nothing maniacal.

No, on the contrary: it educates humanity, it produces the great individuals of which our time so terribly lacks, it gives power and might and the holy criminal courage that until now has created everything mighty.

Yes, he certainly has that, Herr Editor! Only the ‘megalomaniac’ consciousness has the great energy and cruelty, the courage to destroy, without which nothing new and splendid comes about.

By the way, hm, it is indifferent whether one has it; the main thing is that one *must* have it! yes, *must*…

Again the unrest and fear rose high in Falk.

“No, it is really terribly idiotic to waste our time with stupid conversations; this empty threshing of straw. No, to the devil, let’s be merry, let’s drink! The riddles of life… hey! Herr Host! another bottle!”

And they drank. Falk was very nervous. His mood communicated itself to the others. They drank very hastily.

Soon the editor had drunk beyond measure.

“Yes, he loved Falk above all; he would consider himself happy to have him as a collaborator.”

Falk had definitely promised him to send regular reports from Paris to his *Kreisblatt*.

The doctor giggled.

“*Elbsfelder Weekly*: two columns ads, regular reports from Paris! Ha-ha-hah, where is the village Paris?”

The editor felt mortally insulted. Falk listened into himself.

An infinite longing for his wife dissolved in him. Yes! her bodily warmth, her hands and arms!

Strange how Marit had completely left him; no trace of desire. He broke up.

When he came home, it was already day. He cooled his eyes in the washbasin and opened the window. Then he wrote the following letter:

My dear, above all beloved wife!

I am drunk with my love. I am sick and wretched with longing for you. Nothing concerns me in this world except you, you, you!

You love me; tell me how you love me, you my, my everything!

And when I am with you, how will I find you, how will you be to me? Am I still to you your great, beautiful man? Why was your last letter so sad?

How everything in me groans for you! How I long for you! Tell me! am I to you what you are to me?! – The light, the life, the air: everything, everything in which alone I can live? For you see: now, now I know

sure: never have I known anything more surely: I cannot live without you! no, really not.

Only love me! Love me beyond your power; no, as much as you can. You can very, very much! Only love me, love me.

I will write a whole literature for you, just so you have something to read. I will be your clown so you have something to laugh at. I will crawl under your feet, like a slave I will serve you, the whole world I will force to its knees before you: only love me as you loved me, as you perhaps still love me. I will with absolute certainty leave here in two days… Your husband…

But when Falk had slept it off, he made five days out of the two—after which he took the letter to the post.