The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

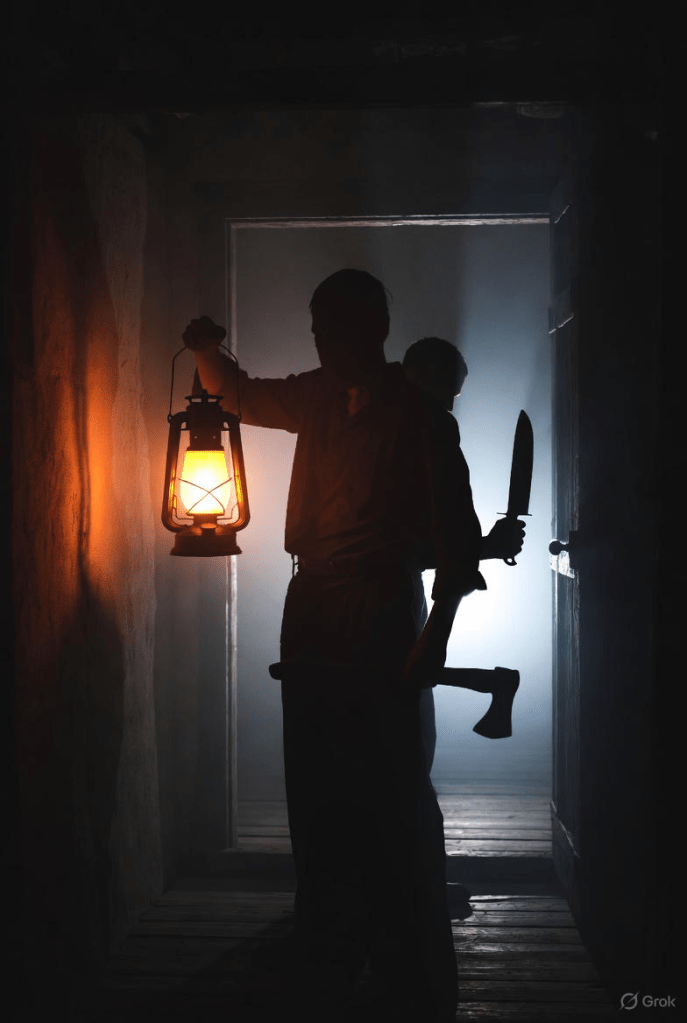

“A knife hangs – falls -. -Ah!”

A shriek came from her mouth. She squirmed in her chair,

half opened her eyes, so that one could see the whiteness,

jumped up briefly in the chair and fell back heavily.

Everybody had jumped up.

“A hysteric,” someone said loudly.

“For today the demonstration is finished,” sounded the

voice of the man standing next to her. “I hope that the

gentleman has not been left unsatisfied, namely the gentleman

who has had his rooster stolen.”

Someone gave a forced laugh.

Everyone was pushing towards the exit, pursued by the

sneering looks of the pale man.

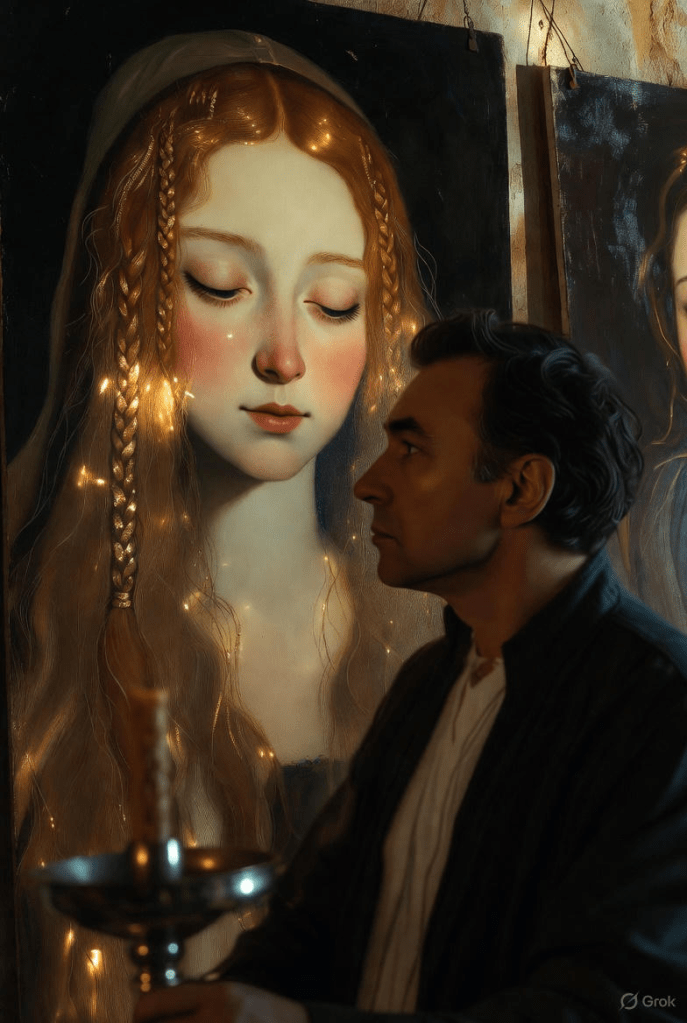

I looked around once again. The girl was awake, looking

around confused and astonished.

A shiver ran down my spine, as if death were standing

behind me. We hastily descended the stairs.

“It’s a pity I didn’t ask to know the day of my death,”

crowed Magister Fleck. “Could have made my dispositions in

good time.”

“You did well to omit that question.”

It was Doctor Schlurich who spoke these words.

No one made any reply.

In the thick, gray river fog that rolled through the streets,

we parted.

Silently I walked next to Doctor Schlurich.

“I suspected that she was deceiving me. But it hurts when

you know for sure,” he said softly.

He shook my hand and disappeared around the next

street corner.

Far and near sounded the calls of the patrols and

watchmen.

“A knife hangs – then falls -“, The Pythia had shouted.

Icy cold crept under my coat and shook me. The handle

of the bell pull at the inn was a small, brassy hand, a small,

cold hand of death.

When my extra mail coach had crossed the French border,

and the horses had to be fed and watered in a respectable spot, I

went to the inn and had an egg dish prepared for me.

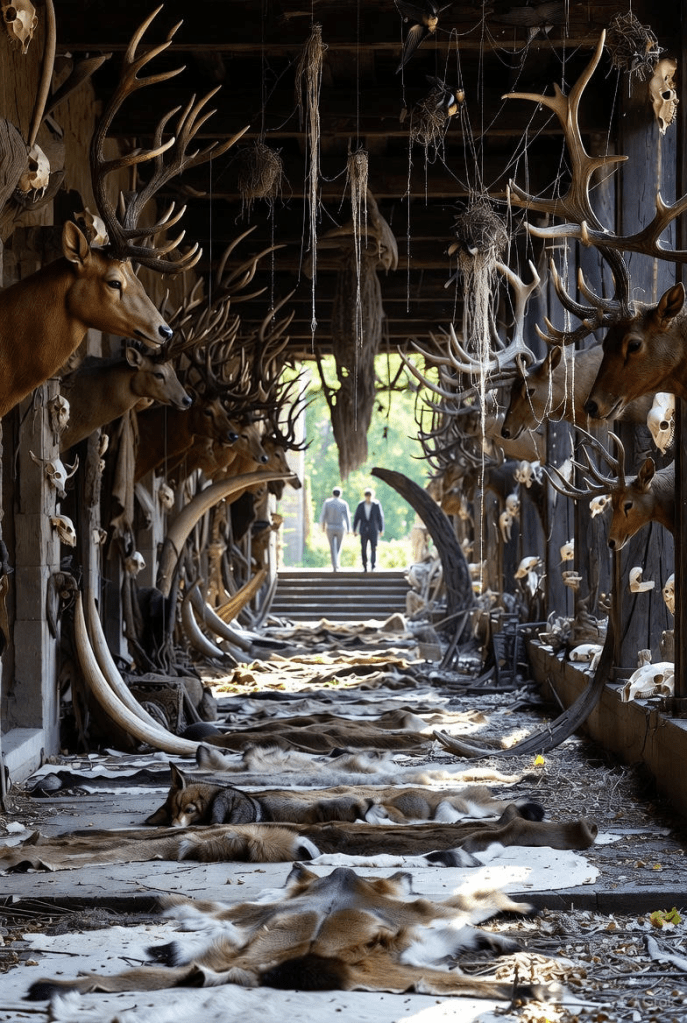

The tables around me were full of people. Carters,

peasants, merchants, burghers and craftsmen were discussing

with all the liveliness of their nature the latest incidents, the

increasing frequency of executions. Recently, very close to this

place the castle of a very haughty and extremely hard-hearted

Viscount against lowly people, was stormed by the peasants

and after a thorough plundering was set on fire. Some of those

who drank the thick red wine openly boasted of the deeds they

had committed.

When I heard how beastly the people had been in the

priceless library and in the picture gallery of the castle, how

they had used the porcelain as chamber pots before smashing it

as night crockery, I had to think of the words of Doctor

Schlurich, who warned me against observing revolutions at

close range. Then, when a very ugly, badly scarred fellow

started to boast, bawling, how he had speared “Bijou”, the

favorite dog of the lady of the castle, on a pike and carried it

around squirming alive for an hour whimpering, until it finally

died in pain and fear, I was seized by a furious anger against

this two-legged beast.

But immediately, like a black cloud, the memory of a dog

fell on me, whose faithful love I had destroyed in a senseless fit

of rage with a deadly stone throw. No, I had no right to be a

judge, even though I had only acted in a violent fit of temper,

but this man, however had acted in diabolic malice.

Tormentingly the thought rose in me that there were people

who were evil by nature -. What should happen to them?

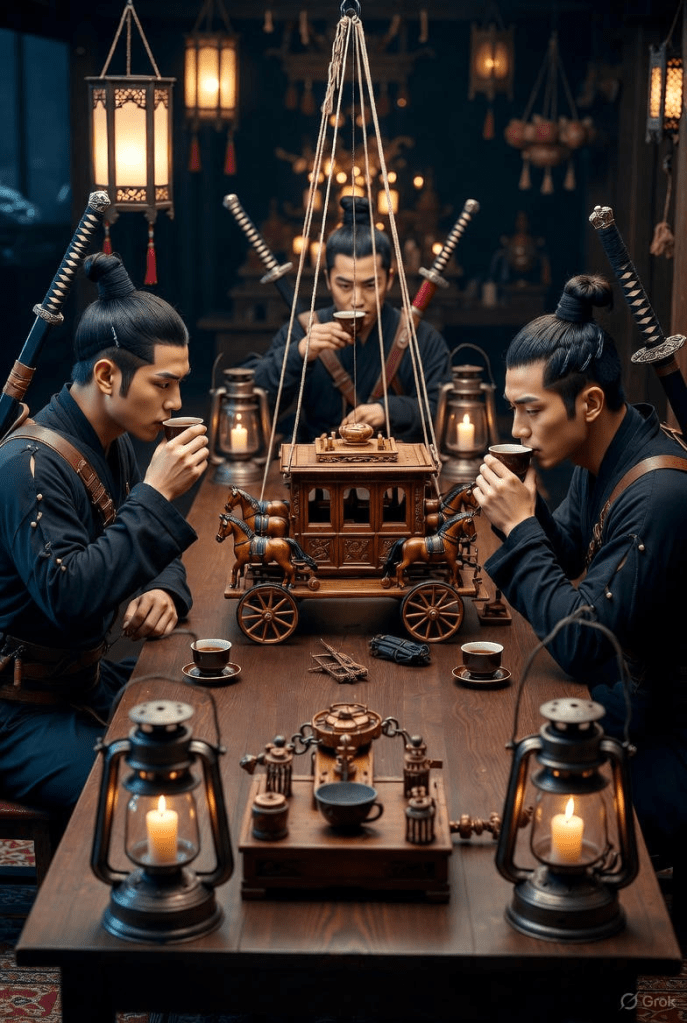

“Melchior Dronte!” fluted a repulsive voice. “Melchior!

Beautiful Melchior!”

I was so frightened that I almost knocked my wine glass

off the table.

I looked to where the voice had come from, and saw an

old woman, covered with dirt and rags, sitting at a table. She

had a box of multicolored slips of paper sitting next to her,

from which a short pole with a crossbar was sticking up. But

on the wood sat a parrot, in whose blue-gray, wrinkled skin

only a few quills were still stuck, while the large head with the

rolling eyes was wrinkled and completely bald. The woman,

noticing my gaze, hurriedly stood up, approached my place and

after she had slung the strap over her shoulder, blew her

burning breath into my face:

“Beautiful, young Herr, Apollonius will tell you

prophesy!”

Despite her pitiful appearance, the dripping drunkard’s

nose and the inflamed eyes I recognized in her the beautiful

Laurette and in the parrot, the monster of the Spanish Envoy. A

sharp pain went through my heart when I compared the image

of Sattler’s Lorle against this gruesome, lemur-like apparition.

Although the infernal parrot had called me by my name, there

was not a spark of memory in her poor, devastated face. Instead

I recognized in the squinting look of the bird such a rage that I

could not free myself from a feeling of fear. The dull, old

woman, who had once been young, rosy and innocent in my

arms, looked at me out of half-blinded eyes and repeated the

slurred phrase from before. I slipped a coin into her gouty

fingers, which she put in her mouth in a disgusting way for

safekeeping, and I saw with satisfaction that for the time being

no one was paying any attention to us.

“Sicut cadaver -,” chuckled the bird. “Kiss her like a

corpse, fair Melchior!”

I approached him and said, as if speaking to a human

being:

“May you soon be redeemed, poor soul!”

Was it really I who suddenly found these words?

The parrot looked at me with a fixed gaze. All malice

disappeared from his eyes, and two large tears rolled down his

beak, as I had seen before. It was eerie and poignant beyond

measure.

“Misericordia,” he groaned. “Mercy!”

And then he hurriedly climbed down the short pole,

rummaged back and forth with his beak in the colorful papers

and grabbed a fiery red one, which he held out to me.

I took the paper from his beak and gave the poor Laurette

a gold piece and nodded to her.

Not a ray of remembrance flickered in her features.

With her box, on the crossbar of which the parrot

lowered its head on her bare breast, she shuffled to the nearest

table.

“O mon Dieu!,” cried the parrot, and the hopeless tone of

this lament went through my marrow and legs.

“Keep your basilisk quiet, you old bone box,” cried a

carter in a blue smock at the neighboring table. “No one

understands its own words. There are no loud aristocrats here,

who take pleasure in such silliness!”

“Why don’t you turn the collar on that stinking grain-

eater, Blaise?” shouted a miller’s boy covered in white dust.

“And if you get your hands on an aristocrat, by the way –

I’ll be happy to help you!” he said, half aloud, with a wry look

at me.

Startled, the old woman limped away from the table and

huddled in her corner again.

I observed the people, who were mainly given to boastful

speeches and certainly not all of them were malicious, and

drank my wine slowly. Besides, I had to wait for the new mail

coach driver before I could continue my journey.

I put the red square slip of paper from the box of the

beautiful Laurette down on the tabletop, and although I told

myself that such things could have no meaning at all, I had to

remember that Apollonius had selected this note for me and I

wanted to pay serious attention to it. In bad print under a series

of astrological signs was written:

“There is a great danger threatening you, which is not in

your power to ward off. A tremendous change will happen to

you, but fear nothing: for you it will be nothing more than the

precursor to a new life.”

I could not see anything else in this writing other than the

ambiguous and naturally quite indeterminate nature of such

fortunes which are given for a piece of copper, and selected

from the heap of similar ambiguous sayings by an animal

which is usually trained for this purpose, nevertheless this

small piece of paper moved me in a significant way. And even

though I was distressed at Laurette’s fate, the fate of so many

careless and frivolous girls and women, I was almost more

moved by pity for the soul, which in a miserable, slowly dying

bird body had to atone for a terrible sin unknown to me. I was

heartily pleased when the new mail coach driver, a young

Frenchman adorned with the tricolor cockade, came in and then

politely asked me to get ready for the onward journey.

As I left the room, it was as if I heard scornful laughter

and swearing aimed at me. I made an effort to remain

completely calm and to excuse the groundless bitterness of

people because of the injustice that had been inflicted on them

for many generations.

I was quite happy when I drove away in the coach.

Admittedly, I was accompanied by all kinds of heavy thoughts.

The sight of my former playmate, whom I had left in splendor

and glory in Vienna and found her here as a pitiable, and

trampled person deprived of reason, and even more the eerie

encounter with the ghostly bird Apollonius, in which a damned

soul was atoning, and lastly, the painful observation that

undiscriminating hatred and blind vindictiveness rose up like

an ugly layer of mold in this image of a great national

revolution – all this saddened me very much and almost made

me regret having undertaken this dangerous and exhausting

journey. But at the same time, I felt the compelling necessity of

a fateful decision, which drove me on and perhaps even more

than that: the desire that came from the depths for the

fulfillment and completion of what I had been destined to do.

Also the conversation with the new coach driver, which

he began with me, half turned back, did not help to cheer me

up. He saw; that I was a gentleman of distinction, and in spite

of the drivel about freedom and equality, this was a source of

refreshment to him. Every day he had to deal with the lowest

classes of society, who made big words and boasted of their

bad manners. Nevertheless, the farther we got into the country,

the more he wanted to advise me all the more urgently to howl

with the wolves and in particular not to meet in public places,

as I had just done, to stay away from the mob. Nothing irritates

the rabble more than silent disrespect, for which the otherwise

thick-skinned fellows have an exceptionally sensitive feeling.

There was nothing else to do than to leave pride aside and be

fresh with every brother and pig. For the time being, only the

most hated and well-known oppressors of the common man,

who succeeded in getting away with their bare lives, should

still be happy. But as the signs were, it would soon go against

all the nobles, but then also against those who were

intellectually superior to the lower people, since they were

considered protectors and friends of the old order. Whether the

individual lived righteously and honestly, whether he perhaps

had even been a faithful helper of the poor and oppressed, or

even suffered hardship for their sake, blood-drunk mobs did

not think about that.