The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

“At the risk of disturbing your meditations, I would like

to ask you, with your kind permission, a few more serious

questions, the answers to which I am very anxious to hear.”

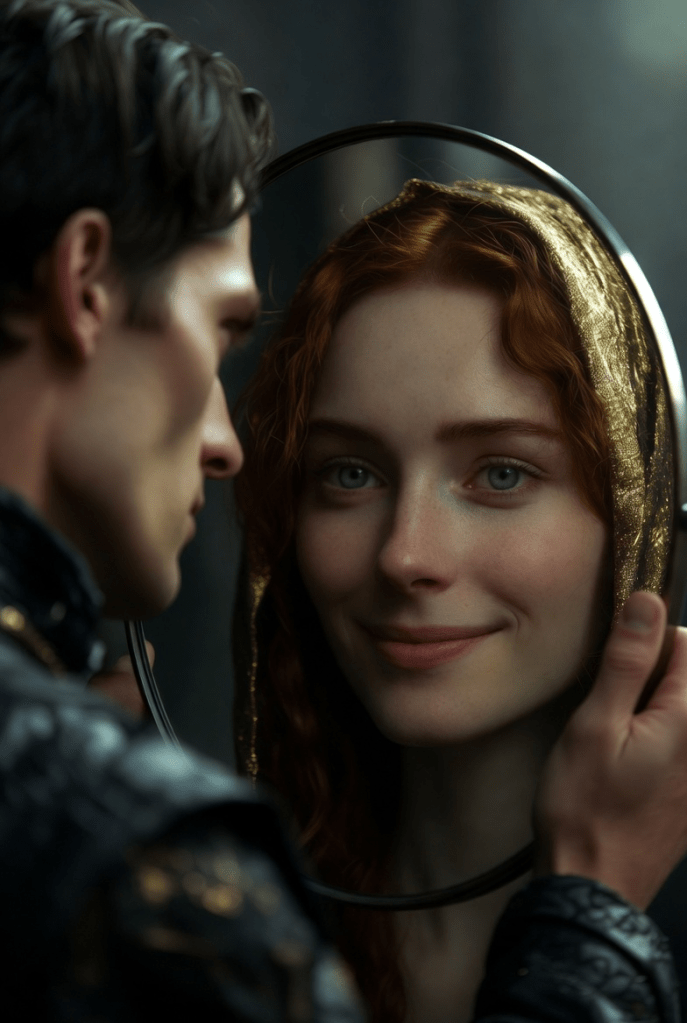

With a quiet unwillingness I tried to recognize the facial

features of the interrupter. But I could only determine that he

was no longer young and that his white and very narrow hands

were folded around his knee.

“I am glad to be at your service,” I said quietly, so as not

to disturb the deepening silence.

The unknown man moved with his stool close to me and

whispered, as it seemed to me, in some agitation:

“All of us, who are here, so far as human calculation is

correct, will be sentenced to death in a few days. In the

certainty that our life, which would lead anyway to annihilation

will now be completed more quickly than nature demands,

there is nothing frightening for me. Another question worries

me, my lord. What happens, when the path of life, which leads

from the brain to the most distant and smallest parts of the body,

is cut by the axe?”

“Any doctor can tell you,” I answered.

“What happens is what we call death.”

“What we call it!” hissed the stranger close to me. “But

have you never heard that the severed heads are still alive? Do

you know that they move the eyes, the hairs stand up straight

against the walls of the basket? That they look in the direction

of the caller, when their name is called, and form clearly

recognizable words with their lips when they are asked? How?

Come to me, esteemed one, but not with Doctor Galvani’s frog.

Here we are talking about the ability to think, to be conscious–

“

“The problem is idle in a higher sense,” I said, “even if

we assume that the cut-off head still thinks and tries to act, this

lasts only a few seconds as a result of the lack of blood supply.

Then the standstill is there.”

The man slid his stool even closer.

“Good, good,” he said excitedly. “Let’s not bother with

that. It is indeed of little importance. What however, is death?

Is it the death of the body and the freedom of the soul, or are

the body and the soul so much together that one dies with the

other? Can you give me a comforting answer?”

The last words sounded like a plea. It had become

completely quiet in our dungeon, and nothing could be heard

but the stomping of the guards in front of the windows and a

soft whistling, the breath of the sleepers.

“Since you seem to be interested in the opinion of a

stranger, I will answer you. Now then, my dear Herr, I believe

that after death, the soul is separated from the body and enters

the eternal life from which it comes,” I said in a muffled voice.

He shook his head vigorously.

“The priests of all creeds say such things. But no one can

imagine what they are really saying. What do you mean:

Return to eternity? Without the artful apparatus of the brain,

the soul is incapable of expressing itself. What becomes of it?

A vortex of air, a cloud of smoke, transparent ether? Where

does it go?”

“It goes into a new vessel.”

I felt as if someone else was speaking out of me. I had

never thought this thought, and yet now it was there as if I had

always carried it within me.

The other laughed unwillingly.

“Into a new vessel, that is, a new body! Here is already

the absurdity. The number of departed are so great that not

even a thousand of them can find a new home.”

I listened to the inner voice.

“Whoever can preserve the consciousness of his earthly

existence beyond death will be reborn in a human body. That is

my belief.”

“And if it succeeds – how often would such a return have

to take place?”

“As often as needed until the soul is purified,” I replied,

moved.

“And then?”

“Then the soul rests consciously in God.”

The man struck his knees with his fist.

“Always the same old stories! Purified! Pure! And the

hatred? The burning greed for revenge, the rage beyond the end,

the hope to retaliate a thousand fold?”

“These are all impurities that must fall off,” I repeated

what my inner voice said. “In the purification of purgatory -“

“Purgatory?” he cried out. “You talk like a Catholic priest.

Where is it supposed to be, this fabulous purgatory?”

“Here, it is life. Life in human form or -“

“Or?”

“Or in the body of an animal,” I said, and saw in my

mind’s eye how tears were streaming from the parrot’s ugly

spherical eyes.

“But these are theories. I want certainty -“, my late

companion insistently demanded.

“There is only one certainty: that of feeling.”

“Faith, then, my lord.”

It was I who spoke thus.

“Fairy tales, my lord, fairy tales. I will tell you what is

after death: nothing is. And that’s the terrible thing, this

extinction of being. To have never been! It is horrible. And I

don’t need to believe in it. I know it.”

“I’m sorry I couldn’t bring you more comfort,” I said, and

was seized with intense pity.

“It is my fault,” he defended me politely. “A few days

ago I spoke to ‘Abbe Gautier before he was executed. An old

man with white hair, a worthy priest. He was struggling to find

a hunchbacked quack- who had been convicted of common

crimes, and pointed him to the infinite, eternal goodness of

God. But the Italian with the hump would have nothing of it

and kept shouting:

“Niente! – Finito -nulla. Nix immortalita – o Dio, Dio!”

“Then why did God call upon him?” I asked.

“Out of habit, I guess. That good Abbe Gautier said about

the same thing as you. I envy him and you. Sleep well!”

He slipped into a dark corner with his stool. I heard him

sigh deeply.

A bunch of keys jingled. The iron door creaked open.

The sleepers groaned unwillingly, turned around, and muttered

unintelligible words.

A turnkey, carrying a large, dimly burning lantern,

entered, and followed by a commissar with a tricolor sash.

Carefully he examined the paper that the official had handed to

him, and then called out half aloud:

“Citizen Dronte!”

I stood up and saw the commissar make a violent

movement of surprise or of joy. He took the lantern from the

overseer’s hand, motioned for him to stop at the door, and came

quickly towards me.

“I am Commissar Cordeau!,” he said hastily and quietly.

It was Magister Hemmetschnur whom I had taken from

Krottenriede.

“I can only stay for a minute,” he repeated in a

monotonous, indifferent voice, while the lantern in his hand

clinked and trembled.

“I went to all the prisons when I found your name on the

list. This is the last one. I know everything. As many of the

cursed Aristocrats I have sent to the Orkus. I would go back to

being the poor miserable Hemmetschnur on Krottenriede if I

could save your noble life, which is so dear to me. Do not

move, do not speak. There are spies in every dungeon, even

here. I’ve spoken to the chairman of your tribunal. The charge

is false. It was not your intention to free Lamballe, but rather as

a loyal supporter of the Republic, you wanted to prevent the

ignorant people from a rash act through which the discovery

and exploration of the dangerous plans in which the princess

was involved are now forever impossible to determine. They

will believe you. You were providing an important function

that will protect you forever. Do not move your head. You must

accept. Otherwise, you will be lost. If you have not understood

me, clasp your hands together as if pleading. You don’t? So you

have understood everything. Now a necessary comedy begins.

Do not be frightened of me, who would like to kiss your hand.”

And with a loud voice he continued, “So you refuse? You want

to know the whereabouts of the escaped traitor? Good. You will

stand in front of your judges tomorrow. Don’t forget that the

lictors’ bundle also contains a hatchet.”

Seemingly angrily, he stomped up and waved at the

turnkey.

“Citizen Gaspard! You’re liable to me for this dangerous

person!”

The turnkey shone his light in my face and grinned:

“This head is loose! I’m getting the hang of this thing,

Citizen Commissar!”

Laughing, the magister slapped him on the shoulder, and

they both left the dungeon. The door slammed shut with a thud,

the key rattled.

“Francois!” scolded one in his sleep. “See, which of the

cursed peasants drives over the inner yard.”

Then there was silence. The darkness dripped down like

pitch.

Before me in the darkness I saw the face of Isa Bektshi.

The kind gaze was directed at me. The narrow scar between the

eyebrows shone like the dawn.

“I will not lie,” I said to myself.

I saw nothing but the black night and I stretched out on

the thin straw of the floor to rest a little. After breakfast, which

the turnkey brought in on his board, a commissar appeared

with several soldiers and brought three of us, including me, to

the court session.

A young, pretty woman, who had mostly been sitting on

a cot, crying, and had received little notice by the ladies in my

prison, was brought in with me and a tall, very haughty looking

man in a dark blue, gold-embroidered jacket and white

stockings was led away. The name of my fated companion I

had not understood when I was introduced yesterday. The only

thing that struck me was the deference with which the

aristocratic prisoners had treated him, and his careless,

condescending manner with which he had spoken a few words

to this one, then to that one, while he hardly noticed me. I was

walking behind these two, the woman and the haughty man; I

was walking alone between two soldiers who had been

specially commanded to guard me. We were led through a

narrow, terribly dirty alley, in which all kinds of garbage rotted,

to an old building, over the archway of which fluttered the

three-color flag. Then we reached a corridor into a low, very

large room, and had to pass behind a freshly painted cabinet,

smelling of fresh oil paint and then stopped.

The inner elevation, in which I had spent yesterday

evening, was gone from me. The thought that this day was to

be one of my last lay heavy as lead on me and filled me with a

dull ache. Even the inanimate objects around me took on a

strange and unfamiliar ghostly form, and even the early

morning light that shone through the dirty windows had a

mysterious reddish glow.

When a soldier motioned for us to sit down, I was given

the seat between the young woman, who from time to time

sobbed violently, and the gentleman in the blue jacket, who

looked before him with a stern and unapproachable face,

without paying any attention to anyone. Now and then he

would pull out of his pocket a gold can in the shape of a pear

and sniffed it with an extremely affected movement. In front of

us stood a heavy table with carved legs, on which everything

necessary for writing was piled up. On the walls lolled pale,

long-haired soldiers, some of them wearing wooden shoes on

their bare feet, and blowing foul-smelling tobacco smoke from

their lime pipes. They only changed their comfortable position,

when a rumbling drum roll outside the door announced the

entrance of the revolution tribunal.

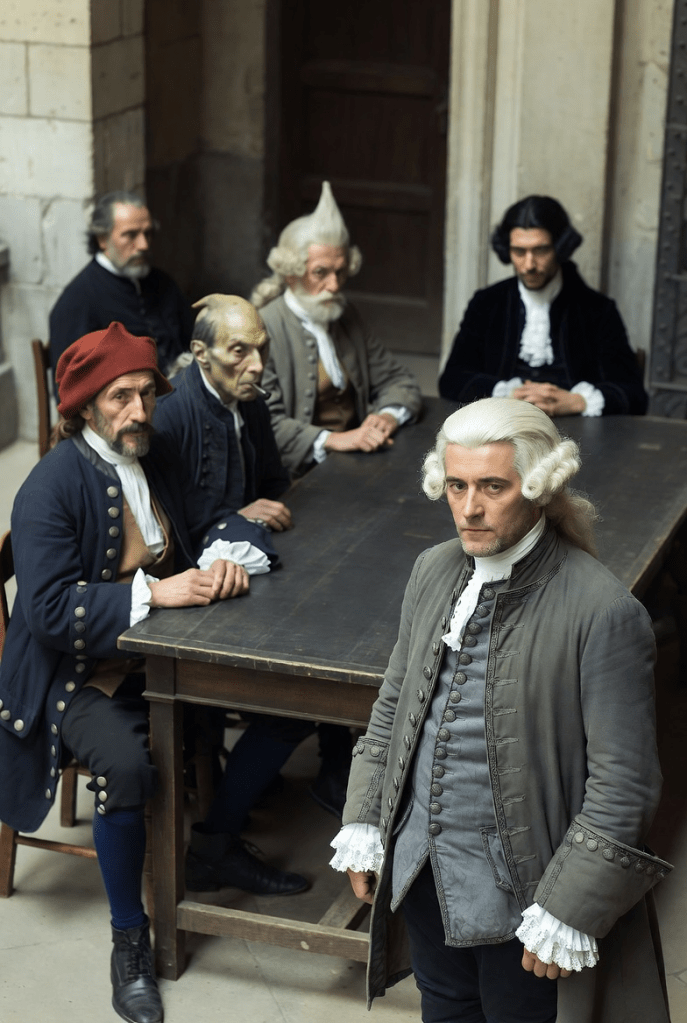

We were compelled to stand and wait until the judges

were seated at the large table. I looked at the men who

presumed to decide on the duration of the lives of others. The

first at the table on the left was a craftsman with badly cleaned,

hands, whose imprint was visible on the rim of his red cap. In

the middle between him and a constantly coughing, obviously

sickly person with pointed, gray-yellow face, was enthroned a

black-haired young man of peculiarly impudent, but not

unhandsome appearance. His restless, dark eyes sparkled under

strong brows, and his long, carefully stranded hair under the

two-cornered hat hung down to his shoulders. He stretched his

legs, clad in white pants and boots with cuffs, far under the

table, waved to an acquaintance in the densely packed area in

the back of the room, and then rummaged with a pile of files

that lay in front of him. Then he spoke a few half-loud words to

the sitters and to the skinny clerk at the narrow end of the table,

propped his elbows on the tabletop, rested his chin on his

clasped hands and looked at us in turn with a look that seemed

to command the highest respect.