The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

I suddenly saw differently, more unclearly, with physical

eyes. My mother was standing in front of me, shaking my arm

violently and shouting.

“For God’s sake! Child, wake up! Wake up!”

I was sitting on the stove bench, so terribly frightened

and breathless that my heart almost stopped. My mother told

me then that she had seen me looking up at random with open,

unmoving eyes. She had asked me what was wrong with me,

and when I did not answer, she went to me worriedly. But

despite the initial gentle touching and then more and more

violent shaking, I sat there as if completely dead, without

breath or any other sign of life, until I finally to her

unspeakable joy came out of the deep faint and back to my

senses.

After half an hour, however, our neighbor, the doctor,

came to thank me for having saved Kaspar’s life with so much

courage and determination. Kaspar had come home wet and

completely frozen to death and had told that he had fallen in on

the arm of the river and had been close to death from

exhaustion. In his fear he had without thinking that this must be

in vain, called my name several times. There I was, who had

probably returned to my usual favorite place, and suddenly

stepped out of the bank of willows, went straight to him, and

with a jerk of incomprehensible strength pulled him from the

wet and cold grave and thus saved him. But when he wanted to

thank me, I was suddenly no longer there and despite all calling

and searching remained untraceable. And then Kaspar,

completely frozen and stiff, ran home, where he, filled with hot

tea, was lying under three feather bed covers and sweating.

It now came to a friendly meeting that ended with mutual

astonishment on both sides, friendly contradiction between my

mother and doctor Hedrich, with my mother pointing out that

she had not left the room for a moment, whereas the doctor

pointed out the specific manner in which Kaspar had recounted

his experience. But when my mother, continuing her

description, spoke of the inexplicable condition into which I

had, however, fallen at the time when the accident happened,

the doctor looked at me with a peculiar look and said:

“Well, well, were you in the end -? But no! Kaspar may

have brought home a little fever, and there the boundaries

between dream and experience disappear!”

With that, after a friendly goodbye, he went out of the

parlor. But then he poked his head once more through the door,

looked at me and said:

“Nevertheless, I thank you, Sennon, and ask you from the

bottom of my heart to continue to watch over my Kaspar, for

you seem to me a good watchman, a Bektschi, as the Turks

say!”

This word, the meaning of which was not obvious to me

at the time, nevertheless put me in the most violent excitement,

and my mother, who must have probably attributed this to the

rising fever, avoided telling my father, who was returning home,

about the incident, probably mainly in order to spare me

questions and thus to spare me new aggravations. It was only

some time after this mysterious event that she told me that a

certain apparition on my body at that time had filled her with

indescribable horror. The narrow scar, which I had as a

congenital birthmark between the eyebrows, just above the root

of my nose, had been visible to her during the unconsciousness

from which she awakened me by force, when a flickering blue

light that looked like the sparks that Kaspar and I let jump out

of a Leyden jar, and this glow went out instantly, when she

shook me hard, but flickered up again more weakly after I

awoke to life, and then gradually faded away. It seemed to her,

she said to me, as if that with the extinguishing of this magical

light my death had occurred, and the thought had shot through

her that perhaps her frightened intervention had suddenly

become fatal to me. Fortunately, I then returned to life.

Later, we avoided talking about the experience any

further, and I believe that she never spoke of it to my father.

But I was so preoccupied with the wonderful ability that had

been revealed to me that it was many nights before I was free

from the recurring dream. Today, on the other hand, I know,

since I have become fully aware of everything, I know that

during those nights, without full consciousness, but also not

completely unconsciously, I left my body and undertook

wanderings, the results of which are too unimportant to be

worth mentioning here.

In any case, the discovery of this power, which I had at

my disposal, brought my thoughts on other and bolder paths

than before, and it was this that was of greatest use to me on

the arduous path to true knowledge.

My and Kaspar’s paths soon diverged to the extent that

insofar as he continued to attend the Gymnasium, while I, at

my father’s request, went to the optic workshop. Because my

parents were poor and reckoned that I, too, would gradually

contribute to the household with love. I was in agreement with

their plan and left secondary school without a moment’s

hesitation.

The fine, great skill and later not insignificant

mathematical knowledge gave me great pleasure. Soon I had

the opportunity during free hours to immerse myself in the

wonderful world of the microscope, and under the guidance of

my father, whose scientific education, despite his modesty, I

began to make all kinds of preparations,

I learned how to color almost invisible cell nuclei and

make them clearly visible, and studied the enigmatic behavior

of the tiniest living creatures, with algae, mosses and molds,

and daily discovered new, wonderful relationships, which

perhaps would have escaped the attention of real scholars, as a

result of their methodical, strictly goal-oriented way of

working.

Thus I was happy in my work and in the security of my

domestic life as only a human being could be. Really there

were little annoyances with young people of my age who did

not want to understand or even considered it disrespectful that I

preferred to stay away from their pleasures and above all

showed no desire for the company of girls, which almost

completely dominated the lives of my comrades. However, I

always succeeded in making them understand in a friendly

manner that the work on my education was above all else and

that the time would probably come later for me too when I

could be accepted into their carefree circle with pleasure.

Gradually I got the reputation of being a strange and

solitary person but I managed to get people to not care much

about me and let me go my own way. My parents, especially

my father, would certainly have preferred it if I had not

separated myself too much from my comrades. But

nevertheless they left me a free hand in such matters and

surrounded me with unchanged and tender love. I suffered

from the fact that I had to be different by nature from my

companions of the same age. But it was precisely in those years

that the insight into the wild adventures of my expired life, as

Melchior Dronte became perfectly clear to me, and the terrible

knowledge about things of eternity worked so powerfully on

me that I urgently needed the solitude, in order to cope with the

impressions that weighed heavy on me.

How I would have liked to have had some person with

whom I could have talked about the survival of consciousness

after the destruction of the body! It would have been a great

relief for me to be understood in the crushing abundance of

contrary views. But with whom would I have been able to

share such unheard-of experiences, perhaps to be attributed to a

diseased imagination, between sleep and waking, death and life?

Perhaps, my mother, insofar as the horror of hearing these

things would have allowed her, with the unfathomable

foreboding of women to have come closer to me emotionally.

But words would have been in vain here, too. So I remained

alone for myself and had to endure the dark agony, of

experiencing once more the events of a past time, and go so

deeply into the night, until everything appeared in the smallest

details as the sharpest memory and gradually blended into the

overall picture that gradually emerged.

How could I have liked the women and girls of the city

whom I knew, since there was only one thing that disturbed the

peace of my soul: the longing for that woman who was

deceptively always disappearing in the double figure of Aglaja

and Zephyrine, and also the only one that could bring

fulfillment to my present life?

And the only punishment that could punish me for the

transgressions of Melchior Dronte, or for my own

transgressions, was the tormenting search, the burning desire

for the face I loved above all else, the brief reunion and the

recent slipping away of this being, to whom I was drawn with

frantic longing.

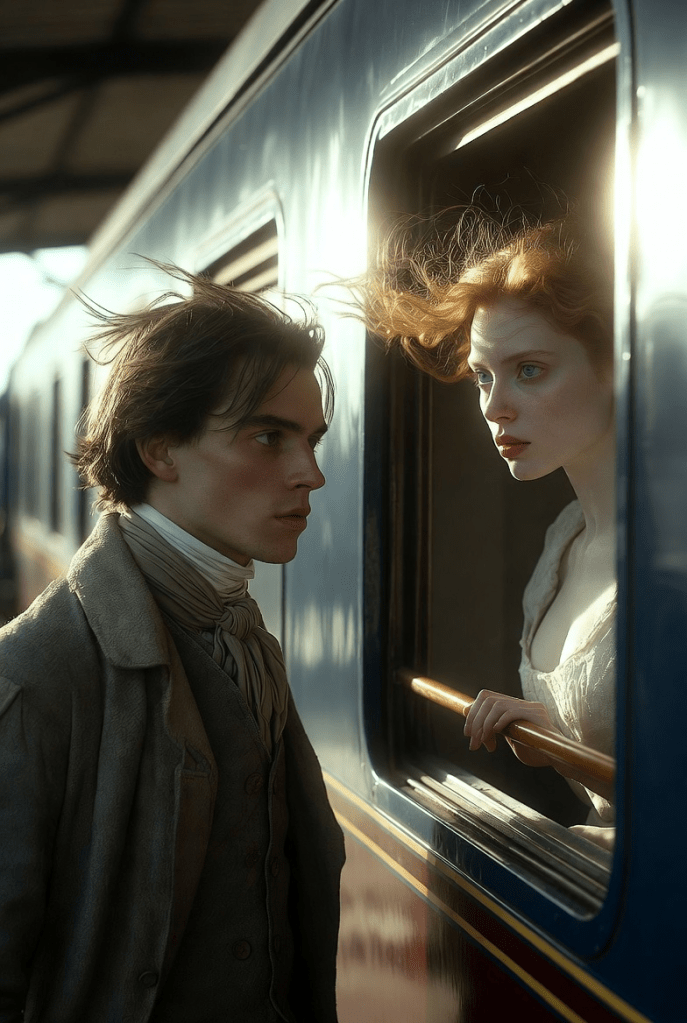

On my eighteenth birthday this happened to me: I had,

yielding to long insistence, arranged a Sunday excursion, with

two friends, to which Kaspar also belonged, which made a

small train journey necessary. We stood at the station in the

early morning of that day, to await the preparations of the local

train, consisting of smaller and older cars, when, with a

thunderous pounding, a long-distance train passed through the

station at a moderate speed.

I was standing at the very front of the ramp and could see

the faces looking out of the broad window frames of the

distinguished train. Most of them were strangers who had

come from far away and were heading for the large port city on

the still distant seacoast, in order to take ships to foreign parts

of the world, especially to the United States.

Suddenly, it was as if a bright glow appeared and turned

everything around me into an almost unbearable light. In a

white dress, pale and beautiful, as I had seen her the previous

night under the flickering of candles in the coffin, Aglaja stood

in the window of a passing car. I recognized her immediately.

Golden red curls blew in the wind around her forehead, her

beautiful gray eyes were fixed on me with sweet terror, and the

small hand that rested on the wooden bar of the lowered

window, suddenly loosened itself and pressed upon the heart

beneath the young breast.

Oh, I saw that she was no different from me, that she

deeply felt that we still had to pass by each other without being

able to hold on to each other, that we were not yet permitted to

unite into one blessed being, the divine consisting of the soul of

man and woman. Certainly she only felt what I knew. But this

feeling of the woman corresponded to the knowledge of the

man and was as valuable and in this case certainly as painful. It

was only a short, agonizing moment, when I was allowed to

see with bodily eyes what once, measured against eternity, was

no less fleeting and transient, and had been close. And it

became clear to me that my way to perfection was still quite far

and that many impure things would have to fall away before I

could enter eternal peace as a perfected one. I was only a

returned one.

Leave a comment