The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

“I wanted to protect the defenseless woman,” I said,

looking him in the eye. He shook his head reluctantly.

There was a murmur.

“Are you a friend of freedom?”

I thought for a moment and then answered the question

with a “yes.”

“Was it known to you that citizen Lamballe had fled to

England and returned from there to Paris?”

“Yes.”

“In that case, it was reasonable to assume that there was

valuable information about her co-conspirators located here

that could be obtained. Not so?”

I was silent.

He looked at me again with a quiet, disapproving head

movement and with a tongue-lashing spoke slowly and clearly,

emphasizing each word:

“I know what you are trying to say, Citizen Dronte. In

your zeal to serve the republic and prevent a premature and

early end of the traitor, you have sought to use violence to

prevent the execution of the sentence. However, you fared

badly enough. Is that so? Give me answer!”

He nodded an almost imperceptible “yes” and waited.

I felt briefly and strongly the lure to return to freedom

from the horror of this justice. But a powerful, insurmountable

feeling inside me made the friendly images of imminent

freedom quickly fade away. I realized, like a holy necessity,

that I had to be hard and merciless against myself, otherwise I

should be thrown back into levels from which I had ascended

and not allowed to higher ones whose aura I had attained.

“I have tried to save the princess on the basis of feelings

of a personal nature!”

The chairman heaved a sigh of annoyance, swayed his

head, drummed on the table and raised his eyes to the ceiling.

The committee members looked at me bored, and in the

auditorium a yawning voice said:

“These are quibbles, Jeannot – Do you understand any of

it?”

“In a nutshell: you had no intention of protecting the

woman as such, but rather to render a service to the Republic.

We have no time, Citizen Dronte, and I hope that your sincere

admission of this fact will settle the case!”

A cold breath passed over my face. The scales stood: a lie

had to sink the bowl —

“I did not think of the Republic in my deed!”

Now it was spoken.

Great unrest arose. Even the drowsiest among the

listeners understood, awakened to irritated attention. The face

of the chairman turned red with anger. He threw his head back

so that his hair flew and hissed at me:

“You dare tell me that?”

“It is the truth,” I replied.

It was clear to me that the grateful magister must have

had his hand in this, and it saddened me that his not without

danger effort had now been in vain. But I had to follow the

path that my innermost feeling was the right one, to go to the

end, regardless of the feelings that arise from the body’s

instinct for self-preservation.

The behavior of the chairman changed immediately. A

deep vertical wrinkle appeared between his eyebrows, and he

bit his lips angrily before continuing the interrogation.

“You are a stranger. For what purpose did you come to

Paris?”

“To become acquainted with the Revolution and its aims-

.”

“With friendly or hostile intent?”

“I did not come with hostile intentions.”

“You are a baron. – How can an aristocrat’s opinion of the

Revolution be otherwise than hostile?” suddenly the bilious

committee member intervened.

“Does such a person love the poor people -?” growled the

one with the stained red cap. “How?” he turned to me.

“I love all the people.”

“These are sayings such as every priest has in his pocket

who stands before the tribunal,” the judge snapped at me and

assumed a frowning pose with a lurking look at me. “You have

thus joined the brave ones who have gone the Lamballe way,

not in the interest of the state, but in order to protect the queen’s

intimate for some other dark motive.”

“Don’t make such long stories!” grumbled someone

behind me.

“He’s one of the whore’s lovers, nothing else!”

Shrill whistles sounded.

Wild stomping of feet revealed that the people wanted an

end.

The skinny man talked to the chairman. The latter

shrugged and turned to the other committee member, who

nodded his head vigorously, raised his right hand and dropped

it with the edge on the table. It was clearly understandable what

he meant by this.

The chairman stood up, stretched out his right hand

toward me like a king of the theater, while the left hand rested

on his heart, and spoke with his voice low and rolling the R’s:

“Citizen Dronte is guilty of treason against the

Republic!”

Thunderous clapping of hands resounded. I sat down,

completely calm and certain of the end.

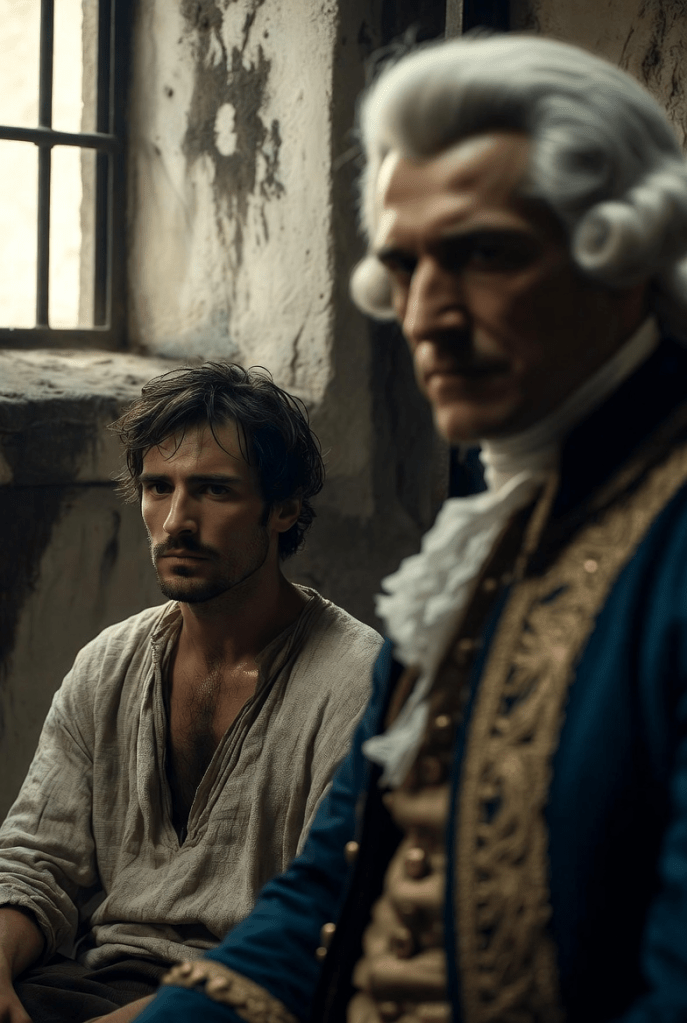

Then the man in the dark blue, gold-embroidered jacket

slowly turned his stern and stony face toward me, smiled and

said very loudly and audibly:

“Allow me, Baron, to express to you my sincere esteem!”

Laughter and jeering followed his words. An apple case

flew past my head and remained in front of the judge’s table.

The theatrical chairman slammed his fist on the table and

shouted, “Quiet!”

Gradually, the scolding, laughing and whistling ceased.

“Citizen Carmignac!” rang out the complacent voice.

The man in the blue jacket stood up.

“I am Philipp Anton Maria Marquis of Carmignac, Pair

of France, Privy Councillor of His Majesty the King, Chairman

of the Breton Chamber of Nobility, Commander of the Order of

Louis —“

The hall cheered. This tall man and his proud manner

promised a spectacle. The emphasis on his rank even evoked a

certain respect.

“He looks well, the marquis,” someone said.

“But his neck is as thin as that of Lamballe’s lover,”

laughed in response.

“Curses! And the thing is settled.”

The marquis took a pinch from his little gold pear and

carefully patted his brocade vest with a small lace cloth to

clean off the tobacco dust.

“You are accused of -,” began the presiding chairman.

“Above all,” said the nobleman with inimitable

haughtiness, “I wish to make the declaration that the privileges

to which I am entitled have been violated with unlawful

violence and I was brought here by unlawfully armed persons.

Now, as to this court I note that it is not made up of royal

courtiers, but of a bad actor, a master carpenter and a runaway

servant of the church, “and therefore offers no cause for further

consideration.”

After these words the marquis sat down, contemptuously

staring into the air.

For a few seconds there remained silence. The

stupefaction was general. But then arose such a thunderous

noise, such a roar of anger that the soldiers present were hardly

able to hold back the frenzied crowd. Meanwhile, the presiding

judge stood up. One saw him waving his hands urgently to call

for silence. It took long enough for him to make himself

understood. He directed an angry, scornful look at the count,

who looked past him equanimously.

“Citizen Carmignac, I demand that you stand up before I

have to use violence and give the tribunal of the people the

homage it deserves.”

The marquis shrugged his shoulders and nonchalantly

stood up on his feet.

“I do not wish to get dirt stains on my jacket,” he said.

“For this I rise.”

The actor sat down and pushed his chin forward.

“If I understand you correctly, Citizen Carmignac, you

fell asleep before the revolution and still haven’t awakened,

eh?”

The mocked man made no reply. Some people in the hall

laughed.

“You have made an attempt to bribe the turnkey of the

Temple to give Citizen Capet, who is kept there, information

on the successes of the emigrants at the Austrian and the

Prussian court, by means of a small piece of paper concealed in

a gold case, which was hidden in one of six lemons. Is it this

case?”

The hand of the judge was holding a tiny gold case of

elongated shape. The marquis measured it under half-closed

lids.

“Since you are playing court here, you will have to go to

the trouble of proving your accusations.”

The displeasure in the room grew noticeably.

“He shall be embraced by Samson’s coquette!” roared the

voice of one of the angriest screamers.

The courtiers bowed their heads to each other, whispered,

nodded, the chairman stood up and without any movement

pronounced his “guilty”.

The court rose. Four soldiers stepped in to us and told us

to stand up. It was fairly quiet as we were led out of the hall.

The people were satisfied.

When we stepped out of the door, where a new troop of

anxious, well-guarded people of both sexes were waiting to be

interrogated, I felt something angular in my right palm, like a

piece of folded paper, and closed my fingers tightly around it.

We were going a different way than the one that had

brought us here from the prison, under an open portcullis, and

finally found ourselves in a spacious, dry and bright cellar. It

was full of people.

Leave a comment