The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

They had known how to prevent it, if one took them as

symbols of a caste, prevented people from reaching the heights

of a decent life. Again and again shoved the unfortunates into

their doghouses and holes, pressed them into the fronts, and in

shallow dalliance mocked the muffled cry from the depths. At

last, when even the excessively rich resources that had been

withdrawn from the others, ran out, they heaped up the grain of

the fields into locked barns, in order to sell sparingly and with

usurious profits to the starving, during the coming famine.

They had forced a painful bridle between the teeth of the

desperate and tightened the reins, while their whip tore bloody

weals. Thus the masses had now finally burst their bonds in

insane rage and torment, and the dull masses had acquired a

flaming will: the will to destroy, to slaughter, to tear to pieces

the wanton, the tormentors and to wipe them off this earth

forever. Who but knew how to read the people’s faces, in those

faces, in their ignorant and still astonished expressions, he

knew in retrospect that the power that had been shattered, if it

had been used with a little kindness, with wise prudence

humanity, would have endured for a long time and could have

achieved a bloodless, peaceful transition to a more just

distribution of goods. But so it was, as if these kings, dukes,

counts and rulers of all kinds had undertaken the ludicrous

attempt to see how long and to what extent they could torture

patient people, until they would finally rise up against the

burden of tortures. And yet I also felt sorry for them.

I was soon awakened from my thoughts by the senseless

and agitated pushing after me of those who also wanted to be

part of the sad procession.

I was startled when, with a jerk, everything stopped and

the people flowed apart. We had arrived at a not too large

square surrounded by old, steeply gabled houses with

blackened walls; my feet almost sank in a sticky, dark mud that

covered the ground, and I had to find a somewhat elevated spot

on the pavement to escape the vile swamp, whose foul-sweet

haze enlightened me about its nature. Around me was a wild

roar and murmur of voices. All the windows were crowded,

and from there cloths were waving to acquaintances on the

street.

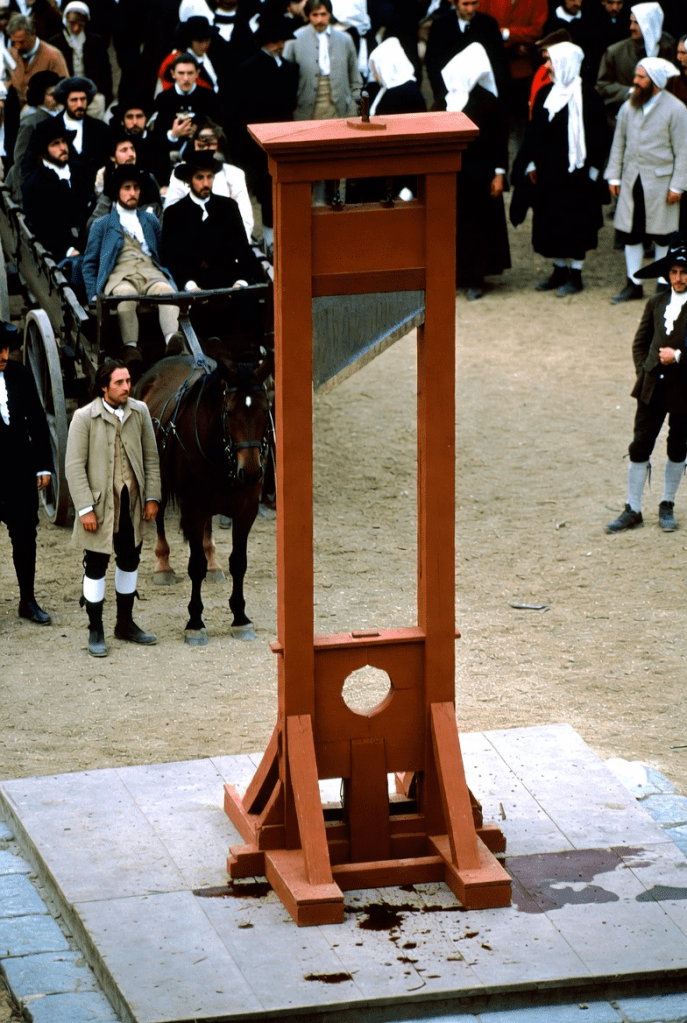

Just in front of me, in the middle of an irregular square,

towering over all the heads, hoods and hats, stood a slim,

reddish-brown, two-footed gallows, on which at the top under

the crossbeam, the drop knife hung slanting and flashing. The

posts, between which it ran, shone dark and greasy in the

daylight, so much was the wood smeared with blood and

human grease. The condemned men rose stiffly and with great

effort from the seat boards of the cart. A horse neighed,

scenting the haze of the square. The poor condemned who had

arrived at their final destination now helped each other politely

and courteously to dismount, the old clergyman made an effort

to help the crippled Doctor Postremo, who was making terrible

faces and chattering with his teeth. I saw the white-powdered

hair of the other and the hunchback’s fuzzy head walking the

narrow alley between the soldiers. The doomed men quietly

and slowly climbed the small staircase up to the blood scaffold.

Abusive words flew at them, fists were shaken, ugly, fat market

women, who stood in the front row, sitting on benches knitting,

were even telling dirty jokes.

I saw exactly every single face and except for Postremo,

who grimaced, they all looked with a stony attitude in face and

gesture towards what was coming. The ring of people around

Guillotine’s machine found itself in grinding motion, and I was

gradually pushed very close, so that the victims stood with

their faces turned toward me. I wished myself far away, to get

rid of the terrible pressure under my heart, with which the sight

of such sad preparations tormented me. But I could not move,

as I was wedged so tightly, I could not even turn my head away

from the tangled hair of an unclean woman who smelled of

garlic, and I had to be sneezed on from behind by a man who

had caught the sniffles. But these small adversities quickly

faded before a nameless horror.

Now a giant swung onto the scaffolding, whose sight

surpassed in meanness everything I had ever seen in my varied

life. On tremendously broad shoulders, over a naked, red-

haired chest and muscular arms rose the face of a devilish

monkey with bared teeth, maliciously glowing eyes and a fiery

comb of red-yellow bristles. Samson, whose portrait I had seen

in a bookstore, it was not. I knew that he was indisposed and

that his first assistant was standing in for him. Horror seized

me at the sight of this guy.

This man-beast, who was followed by two crude-looking

figures grinned, licked his blue lips and then pointed with a flat

thumb at Postremo. The two guys behind him pounced on the

hunchback in an instant, who kicked with his feet, hissed

incomprehensible words and pulled his misshapen head even

deeper into his shoulders. They tied him with lightning speed to

a vertical board, and tipped him over, so that the helpless man

was lying with his chin on a double board, cut out in the shape

of a semicircle, the upper half of which was now pulled down

between the posts and pressed down. A shiver ran through me,

as the red-haired, blood-black hand of the executioner pushed a

protruding knob in the post. The guillotine whistled down.

Something jumped into a basket, the hunched body twisted,

writhing, and flapping its feet, just as poor Bavarian Haymon

did under the murderous ring, and from a huge dark- red

wound, from which a flashing semicircle seemed to hang,

blood gushed out in thick streams, which then gurgled and ran

heavily down the side wall. The executioner’s hand reached

into the basket, lifted the head up high by the stained, white

hair. The axe had not reached the neck, and so the lower jaw

was severed and hung separated with the semicircle of the teeth

on the body, so that I once more saw the mutilated grimace of

the doctor. And this hideous head slowly drew the eyelid over

the right eye, as if he wanted to wink at me.

“It’s not pretty, citizen – but how could he have dressed

up the hunchback angel maker any other way?” said a

craftsman next to me, pulling out a flask from the upper,

opened part of his burn-stained apron smock. “Here, drink once

this will keep the food down if it wants to rise from the

stomach!”

I took a sip of the pungent and burning juniper brandy,

and the trickling warmth inside gave me strength. Once again I

looked around me to see if I could not escape from what was

coming, but it was impossible to squeeze through this wall of

human bodies. A wall was around me that no one could have

penetrated.

So I had to witness the execution of all six condemned,

and each time the leathery clap of the falling knife sounded, I

trembled from my head to my feet. The cold sweat broke out

and my legs trembled violently. The last of the crowd, after the

old lady, who died quietly and without any movement, came

the officer of the Flanders Regiment, who had remained loyal

to the king the longest. He placed himself at the board. While

the executioners nimbly fastened the blood-soaked straps

around his body, he looked at the blood man’s face with eyes

flashing with anger and said loud and clear:

“Do not dare to hold up my head with your paws, red-

bristled pig!”

But the executioner just pursed his bulging lips, waited

for the overturning of the board and the clasping of the neck in

the hole formed by the two semicircles of the double boards,

dropped the axe that the two blood fountains sprang from the

stump of the neck, and reached into the basket.

But immediately, with a grunt of pain, he pulled his hand

out of the basket and flung his index finger rapidly back and

forth in the air, as if he had touched red-hot iron. In a senseless

rage, he kicked the basket several times with his foot, so that

the severed head bounced and jumped in it. Then he hid the

finger of his right hand in his clenched left hand and uttered a

blasphemous curse.

“The aristocrat bit his finger!” The man with the apron

smock shouted. “They are not so easily killed, these haughty

ones!”

Then, as if a bright light shone on me from heaven, I

thought of Isa Bektschi and the parable of the beheaded

evildoer, who used the last of his last strong will with a similar

thought of revenge.

Meanwhile, one of the servants, a jaunty black man,

jumped up to the basket, looked inside, at which the bystanders

had to laugh, and, grasping his hair with two fingers, lifted his

head out. The eyes of the dead man looked half-closed,

contemptuously staring at the gawking crowd, and a thin red

stripe ran down his chin.

Cursing, the redhead climbed down from the scaffold.

In the depths of my soul, I understood the effort of the

priest, perhaps not entirely comprehensible to himself,

although he eagerly displayed it, with which he exhorted the

dying to focus all their thoughts only on eternal bliss,

repentance of sins, and the continuation of life in God, and to

do away with all thoughts of revenge and earthly desires. What

immeasurable wisdom lay hidden in this need, what promise

and what consolation! An indescribably joyful knowledge

glowed through me when I thought of such things and I almost

regretted that my own path had not ended here.

Now that there was nothing more to see, the crowd

loosened and flowed away, getting lost in the side streets. The

windows closed, and the two helpers appeared with water and a

cart on which they loaded the dead remains of the executed in a

crude manner.

I still stood spellbound in my thoughts of Isa Bektschi’s

words, which he spoke to me, when I lay ill in the haunted

room at Krottenriede, when I felt that someone was looking at

me.

When I turned quickly, my eyes met those of a still

young man with a brownish face of regular cut and dark eyes,

from which an extraordinary willpower flashed at me. A great

power emanated from this gaze, with the strange, austere

beauty of the face and the harsh mouth that harmonized.

Leave a comment