The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

“I will venture on it,” I said.

“You, a person of noble heart, will not be harmed by the

room, although –” he faltered and bit his lips.

“Although?” I pressed him.

“I, Baron, would not like to sleep here, and if there were

only one other place in the house, where it does not trickle in

by the ceiling or blow through empty window holes, I would

have chosen it for you rather than this damned courtroom! But

now I wish you a restful night!”

He bowed low and left.

I was alone, and took the candlestick to look around.

The wide chamber had been decorated with precious

leather wallpaper, which was now, of course, everywhere

damaged and tattered on the wall. It showed in hundredfold the

Treffenheid coat of arms with the Moor’s head, which had an

arrow shaft sticking out from the eye. Under it on a ribbon was

to be read the heraldic motto:

“One dies – another lives.”

In the corner next to the door stood a two-sleeper four-

poster bed with twisted columns and angels’ heads, the gilding

of which was worn away. At the lead-framed windows, which

had small gaps, the pale moon wandered behind wisps of

clouds, and a withered, broom-like poplar treetop sometimes

poked at the rickety panes. A table and a few chairs had just

been put there for me, as could be seen from the dust on the

floor.

More remarkable than all this, however, were two large

paintings, which were next to each other on the wall, separated

by a horizontally stretched out naked human arm, extending

from a red sleeve which, was holding a simple executioner’s

sword.

I approached the paintings with the light. The first one

was rich in small figures, and I had to look for a long time in

the restless candlelight until I recognized a procession on the

dark canvas, which was leading the sinner in a cart with solemn

seriousness to the place of execution. Under the picture, on a

white background, it read:

“If you have patience in pain,

It will be very useful to you,

Therefore give yourself willingly to it.”

The unknown painter had understood it, and painted into

the faces of the accompanying persons, secretly and

immediately recognizable to everyone, stupidly proud dignity,

thoughtlessness, malice, cruelty, indifference, and cowardly

contentment; but from the face of the man on the execution cart

cried out fear, and the staring look was almost a longing for the

final redemption by the redcoat, who stood tiny and distant on

the scaffolding.

This image made me fall into a depth of consciousness or

foreboding, which filled me with fearful darkness for several

minutes. It told me that something had happened or was about

to happen, and from my soul a voice spoke barely audibly:

“I know —.”

The roots of my hair were on fire, drops of sweat covered

the inside surface of my hands. But what it was, I could no

longer grasp with my mind, for as quickly as it came, it sank

again into a dark abyss. I turned my gaze from the terrible

image, ducked under the threatening sword arm, so as not to

touch it, and lifted the light towards the other painting.

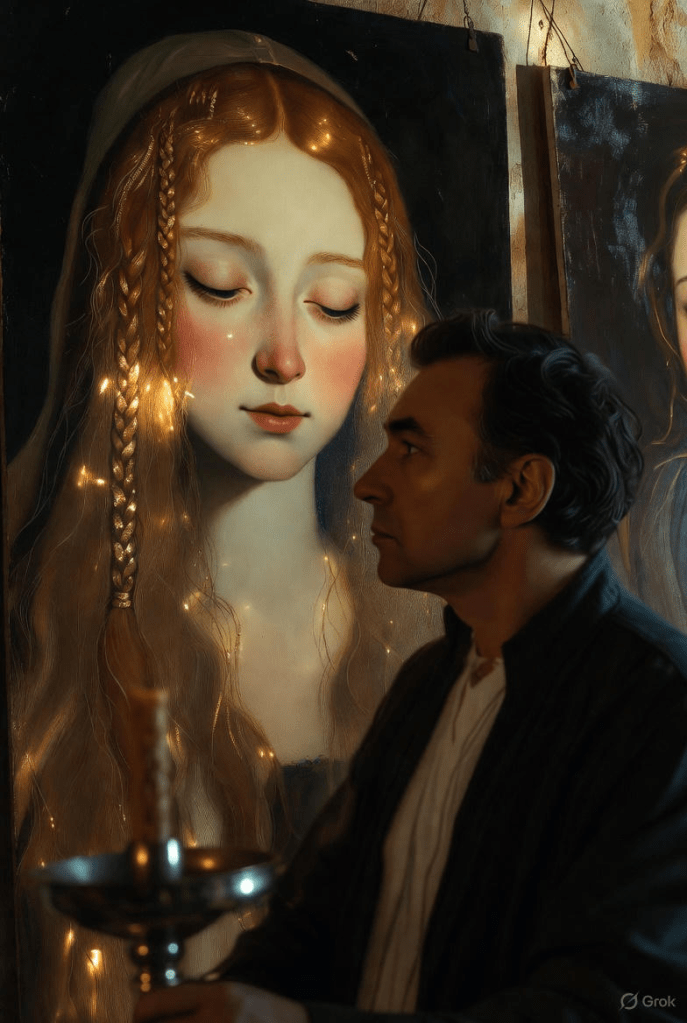

A fine and cutting stab went through my heart. This face,

blissful and childlike, with reddish shimmering braids under a

small hood, with the delicate nose and the small mouth, with

the curved eyebrows, it was…

“Aglaja,” I whispered softly, and the heavy candlestick

almost fell from my hand.

But then it seemed to me as if a sad, dark glow went over

the lovely face. No, not Aglaja! It was Zephyrine who was

looking at me, as if she were breathing. The slender hand,

coming from a lace ruff, wore a silver ring of woven serpentine

bodies with a fire opal and held daintily between pointer finger

and thumb were three crimson roses and a snowy lily. But what

was written underneath, confused me in the face, which always

showed a beloved face. I ran my hand over my eyes and read

the characters under the painting:

Likeness of Lady Heva Weinschrötter,

Canoness to St. Leodegar, accused of sorcery

and sentenced to the sword

In the year anno 1649.

And then I stood for a long time, until the candles began

to crackle and the wax dripped. – What was appearance and

what was truth? The night had passed quietly except for some

creaking and cracking in the room and in the floor as is natural

in such old buildings.

The new day was of dull light and unfriendly, full of

wind and falling drops. There was a rustling in the walls, as of

rats.

The servant, who brought my breakfast, informed me that

the master of the hound was suffering from gout and would not

be visible before the evening. I should not enter uninvited into

his room, because he had a saddle pistol next to him loaded

with rock salt and pig bristles, and in his piercing pain he was

well able to burn one on me and everyone, as he had already

done to magister Hemmetschnur once before.

So I looked once more in the gloomy light of the room, at

the ruined face which was now even more clearly visible than

in the candlelight. I also discovered the trapdoor in the floor,

through which one could enter the dungeons and chambers

under the earth. And whatever I did, the gray eyes of the

painting of Lady Heva Weinschrötter followed me. But as I,

mindful of the evening’s feelings, looked firmly and attentively

at the rosy face under the gold hood, it seemed to me strange

and distant to me. The resemblance to Aglaja-Zephyrine faded

into the distance and finally disappeared completely.

While wandering around in the spacious chamber I

discovered opposite my bed a door so carefully fitted into the

wallpaper that it was easy to miss. When I pushed its creaking

hinges, I came into a narrow chamber with racks, in front of

which were rotten curtains of shot green damask, all covered

with dust. When I pushed them aside, I found in the

compartments whole bundles and piles of old files, and all sorts

of formerly confiscated corpora delicti, such as knives,

hatchets, bludgeons, rotten wheel locks, thieves’ hooks, gypsy

casting rods and the like, and attached to each item was a

carefully written note. Some I read:

“The knife, with which Matz from the Schellenlehen

stabbed Schieljörg,” and “Explosive and grenade called, Reb

Moische, the Hendl from Poland”. Finally I came to an earthen,

smoky pot, blue-glassed, which was tightly tied with a pig’s

bladder and on the square parchment on the handle, was

written in brownish faded ink:

“Numerus 16. Flying or witch ointment, found under the

bed of the lady of hell, and dug out of the earth.”

This relic of one of the women who had stood here

during the inquisition, aroused my curiosity very much, and I

hid it near my bed, in order to visit it later.

At the midday meal, only the magister appeared, who

asked me politely about the night spent and then said that I was

the first to have been granted a quiet sleep in this room. After

the meal I went for a walk with him despite the rain showers

and gusts of wind, and talked to him. The knowledge of this

man was astonishing, his exact knowledge of languages, and I

could not help but ask him, how he, with his erudition, could

not have found anything better than that of his unworthy

clerical services for the old master of the hound, who seemed

to take special pleasure to humiliate and make fun of his

education in front of others.

He heaved a deep sigh and said that if he only had

enough money so that he could reach the city of Paris, or only

to Strasbourg in the former German land, which the French had

stolen, it would be better for him in an instant. There he would

have friends who would gladly continue to take care of him.

But even if he had as much as he needed for the journey, he

would still have to be on his guard. For the master of the hound,

as he said, had already impudently threatened him, the

magister, and would not refrain from accusing him of

embezzlement and to have him punished, which he, as a poor

and helpless man, was unknown and without any ability to

defend himself.

I said nothing, but made up my mind, to help this

unjustly tormented person, if I could.

For dinner, the gentleman from Trolle and Heist was

brought to the table in a carrying chair, his right foot bound

thickly and sweating with pain. It was hardly possible to hold a

conversation with him, and only in view of the fact that I had to

stay here at all costs, I allowed myself to be subjected to

various of his quarrelsome and irritable moods. It was worse

with the magister than with me, he threw a pig’s bone at his

head for no reason and as for the hunters who were waiting for

him, he would spit wine at them or hit them with a stick. At ten

o’clock he began to drink murderously again, and at about

eleven he started his howling anguished chant. But the

intoxication did not work this time, and I saw how he looked in

fear with puffy eyes into the corner of the chamber devastated

by the fall of the wall. Finally- he hurled a heavy mug in the

direction of the apparition visible to him, laughed, and then

sank down, muttering to himself several times something about

a useless rhyme smith and court poet, and then sank into a

frenzied sleep, whereupon they lifted him up in the carrying

chair and carried him away.

Leave a comment