The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

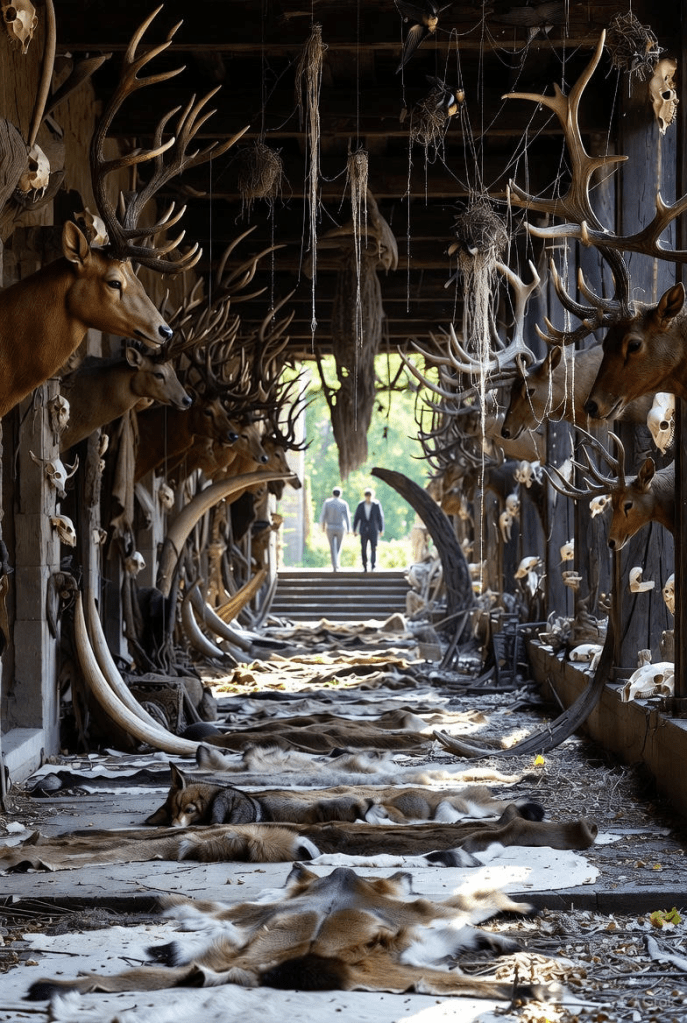

We walked up and down the cool arcade of the manor

courtyard, and I saw, with a tormenting restlessness in my heart,

and indifferently looked at the hundreds of wooden carved deer

heads, boar’s tusks and deer antlers on the walls, from which

long spider threads hung and swallow’s nests stuck. On the

floor lay almost hairless wolf-pelts and worn deer blankets,

which gave the impression of decay and abandonment even

more. And the old man next to me was Heist, of whom my

father had told me that he had killed the duke’s court poet in a

duel, and of whom Gudel had spoken of with disgust.

“Well, well!” said the Master of the Hound, standing still

and stuffed a pinch into his fiery nose.

“Mort de ma vie, you are not a child, after all, Dronte,

and it will not offend you when I tell you that your father and I

were the best sire stallions at court. Isn’t it still told today the

fun of how we stood one of the chambermaids of the duchess

on her head and filled the woman with champagne so that

Serenissimus almost suffered a stroke from laughing? Or how

we pinched the hopeful Annemarie Sassen in the dark on her

firm arse, so that she cried for help and the duchess swore to

have the culprits publicly flogged, even if they were of

standing? Oh, those were good times, wild days! What do you

youngsters know of them?!”

To distract him from those wild memories, which

reminded me in a terrible way of all the suffering that had

come to me from my father, I asked him about the man with the

missing ears who had been sent to find a shelter for my person.

“Him?” laughed the old man. “That’s a former magister,

who went about all over the place and also came to the court of

the grand lord. And there it seems to have gone wrong for him,

for they cut off his ears at the bridge of Stambul. He has lived

here for several years and provides me with board, lodging and

a few pennies, but he is kept quite short.”

Just at that moment the man had silently appeared behind

us; a sour smile on his disgruntled face told me that he had

heard the words of the hound master. But then he said, dryly

and without any raising and lowering of his voice, to his master:

“Accommodation is found, my lord, Master of the Hound.

In the hall of the former patrimonial court, the ceiling is

tolerable and impermeable, in case of new rain. The bedding is

with sufficient linen, the windows are washed and quite clean.

The foreign master can dwell there, if — if namely–“

“Don’t be so long in talking about “if” and “when, but tell

him what the catch is!” the octogenarian snapped at him.”You

educated ass!”

The grumpy one didn’t make a face at this.

“Provided the gentleman is not afraid of ghosts that

sometimes haunt such old chambers.”

“Triple-horned dromedary!” rumbled the hound master.

“Just so it stays in the courtroom! What’s for dinner?”

“Venison with four kinds of brawn, boiled blue tench

with millet porridge and a nutmeg tart,” said the magister.

“Good. Now get back to your writing!”

The gray man walked away with his back bent.

“You don’t treat the poor man very well,” I couldn’t help

from saying.

“That’s how you must deal with such learned dicks or

else they’ll be ridden by conceit and arrogance,” laughed Troll.

“Believe me, Dronte, no one needs to be put down more and

castigated than the learned rabble who stir up the common folk

and make them dissatisfied with us. But now I will show you

your chamber – a rascal who gives more than he has!”

As we ascended the stairs, he asked me, as it were, if I

had any business in the area, and when I said that I hoped to

meet someone here whom I had not been able to identify, he

was satisfied and said that I could remain as a guest as long as I

wished, for he had plenty of food and wine.

Then he showed me the door of my room and reminded

me to be on time for the meal.

With a disconsolate heart I entered the wide room, in

which I now had to stay in uncertainty and wait for Ewli. The

manner of the old man was extremely repugnant to me, and the

form in which he finally offered his hospitality with reference

to the abundance of the food, seemed to me so hurtful that I

would have preferred not to unpack my coat bag at all. Also I

was dreading the constant togetherness with the hearty, by his

age by no means internalized man, and it was completely

incomprehensible to me that Ewli should have chosen this very

place to come close to me. Tormenting doubts came over me

and aroused in me the thought that I had turned in the wrong

direction and could have missed the actual place. But now I

had to good or bad, be satisfied and hope that the man from the

Orient would also know how to find me here, if this would be

in his mind.

Since I would be in the spacious room later I hardly took

any time to look around the barely illuminated and gloomy

chamber. I also found no light, so I hurried with makeshift

cleaning in a metal basin, into which I let water bubble from a

hanging dolphin by means of a faucet, and then went down to

the dining room.

The hall was a reflection of all the misery in the old stone

box. In one corner a part of the wall covering had fallen down

and formed a pile of rubble that no one seemed to have been

obliged to clear away. The darkened ancestral portraits of the

counts of Treffenheid, to whom the coat of arms of the arrow-

headed Moor belonged, looked with white, staring eyes from

the wall, and in a once beautiful, but badly damaged dragon

fireplace blazed, despite the warm day, a huge fire made of

beech logs. At the large, heavy table I sat next to the hound

master in the midst of all the dogs, who were eating chunks of

meat and pieces of cake and biting each other, and at the very

end of the table like a gray shadow squatted the unfortunate

Magister Hemmetschnur. Such was his name, the peculiarity of

which still elicited a guffaw from old Heist, when he

pronounced it, twisted and misshapen in all ways. But the food

was good, and even if the wine in the pewter cups was a bit tart,

it nevertheless pricked pleasantly on the tongue and palate.

After the meal, which proceeded rapidly, the dogs were

driven out, and the old man lit one of the many lime pipes,

which were placed in front of him, stuffed in a cup. When he

had smoked one out, he threw it, breaking it in shards, and

grabbed the next one, so that we were soon sitting in a thick

blue fog, watching the ever coughing figure of the gray clerk

almost disappear in the haze.

I was tired and sad, and also exhausted from the terrible

adventure in the Ball Mill and yet out of courtesy had to stay

and listen to the coarse jokes and jests of the master of the

hound, which were never ending and to show me a picture of

my father, with whom he had committed a large part of his

deeds, that was even more ugly and unpleasant than it already

was in my memory. But since the old man drank intemperately,

his tongue soon became heavy. When the eleventh hour struck,

he opened his mouth wide and began to shout out songs with a

false and booming voice:

“A little rabbit would creep” and “It runs to the wood

unharmed, fellow,” and so on, without pausing, until at last his

bald head sank with a jerk on his chest and out of his open

mouth came a sawing snore and a rattle. As if this had been

awaited, immediately two powerful hunters and a hunter boy

entered, grabbed the hound master by the head, shoulders and

feet and carried him out without bothering about me or the

mute magister. Although curiosity was far from me, I did

nevertheless address a few questions to the man who had been

treated so disdainfully, and who seemed to me to be worthy of

some attention, and I learned that every day at the same time

the intoxication and singing began. And this had its origins in

the fact that years ago, between eleven and half past midnight,

the wife of the master of the hound had found her husband in

the arms of a maid and became so transformed that she was

killed on the spot by a stroke. Sometimes, however, the ghost

of the Duke of Wessenburg’s court poet, who had been killed

by his hand, would appear. This was the reason why the old

man tried to drown out this period of time.

If no one is present, the old man sings alone, but then,

before eleven o’clock, the head hunter Räub must appear with

his hunting horn and stay until the moment he falls asleep, and

then blow the horn as loud as he can. After this explanation,

Hemmetschnur seized one of the candlesticks with five candles

and asked for the honor of escorting me to my bedchamber.

We climbed through the dead quiet house, around which

the wind whined and the poplars rustled, onto the upper floor,

and in front of my door the magister gave me the light, humbly

bowed and wished me a good night.

“Tell me still, Herr Magister, what you meant when you

spoke of a haunting in this room?”

I stopped him. At the same time I opened the door and

invited him to enter the room with me.

He bowed and closed the door behind us, a smile sliding

across his grizzled gray face.

“Certain things I cannot say,” he said, looking around.

“But consider what may have gone on in this chamber for all

the uncounted years, since the jus gladii and the jurisdiction of

it all rested on Krottenriede. People say many things. Like for

example, that old Krippenveit, whom they torqued to death

here, sometimes lifts the trap door in the floor and looks around

horribly.

Or that the horse Jew Aaron, whom they wanted to tickle

for his money, suddenly stood in a dark corner screaming for

mercy. They tortured him here, too, and because he was over

seventy years old, when they raised him, he fell into the

fainting sleep of the tortured, they put boiling hot eggs into his

armpits and pressed them with their arms to get the gold hiding

place from him. But he would rather have died than have given

it away, Emmes gedabert, as they call it in their language,

truth-talking. Up there is still the iron ring on the ceiling,

through which the rope ran. Here they also had the Bee’s Agnes,

also called the honey lick, brought to a confession and then

handed her over to the redcoat, who burned and roasted her and

then buried her at the cemetery of Saint Leodegar with a black

cat and an old hen that would not leave her. The Frau of

Weinschrotter however, a woman of nobility, who grew roses

and lilies from her pots in the bitter winter, was sentenced to

the sword. Her portrait hangs here in the room. You Baron, can

see the crudeness and stupidity of the people that has been

celebrated in this room. From the futile sighs and tears of the

poor, who fell into the hands of these animals and of the

abominable events that have taken place here, a shadow or

image may still adhere to the cursed walls, and for those

predisposed or through special arts those events may appear as

alive once again to suitable persons. That is what I meant.”

Leave a comment