The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

Since the candle threatened to go out, I asked Garnitter to

come out with his treasures, and soon there was a new light

burning in the candlestick.

“Hang cloaks or blankets in front of the windows, so that

they do not see the light from outside,” I admonished, and

immediately they went to carry out the advice. In the meantime

I looked at the door. There was probably a strong wooden latch

on the outside, but there was no way to secure it from the

inside. The hinges, however, seemed quite freshly oiled to me,

and I brought it to the attention of the others.

“That bastard of an Innkeeper is up to something,” the

squire from Sollengau blurted out, “and because there are four

of us, since the drunk is not to be counted, we must be hellishly

on the watch, because the host can get help from the

Spillermaxen Gang or from the blue whistlers.”

I said nothing and continued my investigation. The floor

was made of tamped earth, the walls had been built up with

solid blocks and cement and were ancient, and the ceiling had

no visible opening and consisted of heavy, dark beams, such as

one can only rarely still find in such length and strength.

Then Hoibusch emitted a low whistle and beckoned me

hastily. He was standing by the pillar. We trod on the rustling

straw and followed his groping hand with the light. And there

we saw something that revealed to us the trace of the satanic

trickery that was at play here.

In its entire length, from top to bottom, the rough stone

column was smoothly polished as if something heavy often slid

up and down on it and transformed the roughness of the

friction points into polished grooves. And seized by the same

thought, we looked upward at the ring or the capital of the

column, which with its excessive projection and mighty width

enclosed the column. It stood out brightly white in its fresh

coat of paint, and was separated from the narrow, circular space

of the column itself, so that this heavy load, when it was

loosened at the top, could fall down.

And it was precisely in the area of this ring that our head

pillows were arranged around the column.

Haymon straightened up halfway in his sleep and

stammered with wide-open eyes:

“Don’t you want to rest, Montanus? – You can’t get ducats

from your Mary, brother – let go, put away the blue hand–” and

then he vomited out the wine and food from his stomach,

which had long since been ruined, and defiled himself nastily.

“Pull him away from this death-trap” I shouted.

Then they grabbed him by the legs and pulled him away

from the dangerous bed, but he crawled back in his madness,

while we continued and once again he was dragged away. Then

he seemed to want to keep quiet and remained lying down.

“Shh!” whispered Garnitter, who was listening at the door.

We quickly extinguished the light and stayed as quiet as a

mouse. Light footsteps came along the corridor.

“Bärbel, the false hussy -“.

“Shh!”

She listened at the door, leaned. The wood creaked softly,

Haymon chattered in his sleep.

“What say you of sulphurous flames, Portugieser? – Great

hell, brother, how it stinks from your throat! I won’t give you

my hand, you are black all over, you devil- roast -“.

Quietly she scurried away from the door, down the

corridor.

We heard Haymon rustling in the straw, hitting the floor

with his foot and stretching with a groan.

Footsteps again. The boys quietly drew their long blades;

I drew the pistol, my thumb on the hammer, finger on the

trigger, without cocking it. It coughed, scrabbled at the door.

Then it slunk away again.

“They think they’re safe now, the murderous hounds,”

said Hoibush. On the ceiling above us something slid. A low

rattle arose. A dull unintelligible voice spoke something. A

whirring, a grinding, a whooshing fall–

Boom! – It struck heavy and pounding, softly muffled.

Feet drummed like madly on the clay floor, leathery,

clapping…- in our room.

“Strike fire, Hoibusch!” cried the squire hoarsely.

Pink, pink! The tinder glowed up, the sulfur- twitched

blue and sizzled with acrid stench, the candle burned -.

“Almighty!” Garnitter wanted to cry out, but Hoibusch

quickly put his hand over his mouth.

It took our breath away. The wide column ring had

crashed down and buried the head cushions and the unfortunate

head of poor Haymon, who had crawled back in the dark

without our knowledge. His feet were spread apart, his hands

were clasped on his chest in the robe and the rest of him lay

under the murder stone. Like a thick, dark snake, glistening in

the candlelight his blood coagulated in the straw.

“Lights out!” commanded the squire. “They’re coming!”

Ready to strike, we stood on either side of the door in the

darkness. Speaking loudly with echoing footsteps the landlord

and his pointy-nosed wife came down the corridor and pushed

open the door.

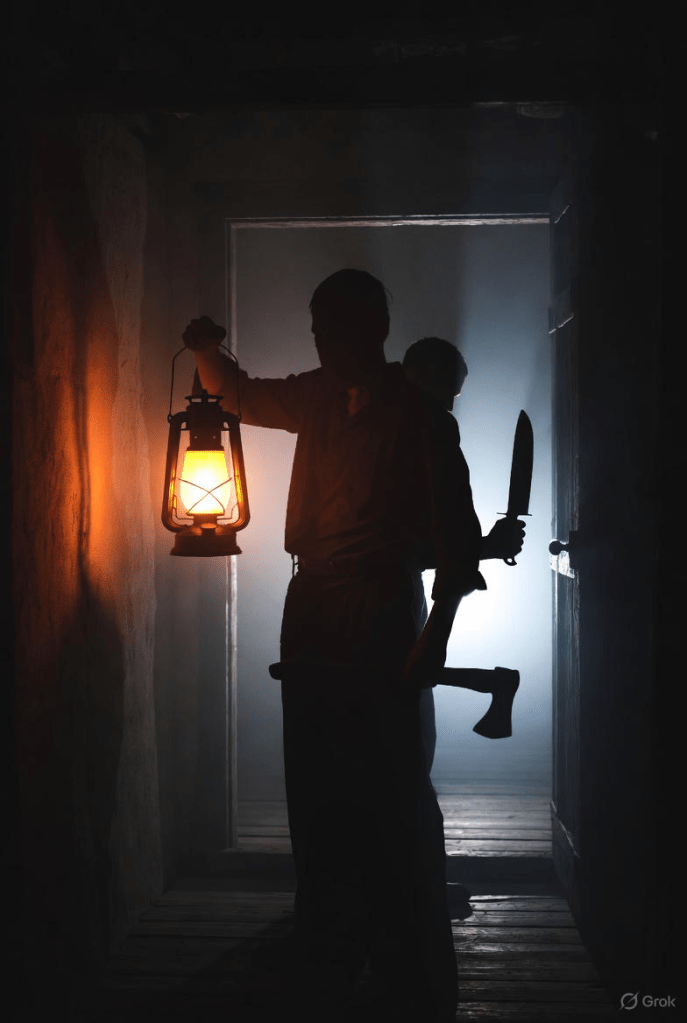

There they stood. The innkeeper carried in his left hand a

large stable lantern, in his right fist a sharp axe, and the fury

behind him was clutching a butcher’s knife. We only saw them

for a moment. Hoibusch’s blade went through the guy, and

Garnitter slit through the yellow neck of the woman, so that she

fell down with the squeal of a stuck pig. The host was dead in

an instant, speared through the heart like a starting boar. The

woman was still wriggling, and then lay still on her side.

“Are you dead, bloodhound?” shouted Garnitter and

kicked at the dead man’s belly with his foot. Up in the house

the dog howled.

“The dog! The wench!” cried Hoibusch. “We have to

catch the wench; otherwise she will run away and send the

host’s henchmen after us!”

He and the squire set off with the lantern to look for the

woman.

Now Garnitter and I saw the four holes in the ceiling and

the ropes hanging, by which the stone could be pulled up again.

We set about freeing the dead Haymon. But the stone was

too heavy for us to lift, and when we pulled on the feet of the

murdered man, the bones of the crushed head crunched so

horribly that we had to let go with a shudder.

Then we heard a shot, the wailing of the dog, and then a

dragging and a whimpering, and immediately Hoibusch and the

one from Sollengau came with the woman in shirt and smock,

whom they had dragged out of bed, where she had been under

the blankets and had fallen asleep. They had tied her hands

with a calf rope.

“I am innocent,” whined Bärbel when she saw us.

“Jesus Maria!” she shrieked out, as she stepped with her

naked foot into the pools of blood in which the landlord and the

landlady lay.

“Confess, whore, or we’ll lay you down next to the two of

them!

Both!” said Hoibusch calmly. “Did you not set the dog on

us? Confess, I say to you!”

“O thou bloody savior! What shall I confess?” Howled

the strumpet and fell on her knees. “I have done nothing,

except that I went to listen at the woman’s command to see if

everyone was asleep. I have never known of murder in my life”.

“And what is this, you shamed woman?” cried Hoibusch

in a strong voice and produced something he had been hiding

behind his back. Stones and gold flashed – a necklace with

almandines and artfully forged links shone in the light.

The girl’s face was white with fear and she looked around

with confused glances.

“Red!” said Hoibusch quite coldly, and put the point of

the blade on her bare breast, so that a small little red drop

sprang up.

“Ouch! Mercy -” clamored Bärbel as she squirmed to and

fro. “From the lady in the cellar -“.

Then she fell down in convulsions, and foam poured out

of her mouth. It was a pity to look at. But Hoibusch remained

unmoved.

“You have learned your art of eye-rolling well, you

robber whore!” he said. “Stop making foam out of saliva, and

get up!”

And once more he tickled her with the point of his rapier.

Then, in spite of her tied hands, she sprang to her feet like a cat

and cried out in despair:

“Well, if that’s what it is, I’d rather be dead right now

than let the gallows man sound me out with the thumbscrews!”

And she made such a swift and violent push against the

drawn blade, so that it missed going through her body by a hair.

But Hoibusch was on guard, and immediately let go of the

handle, so she only slashed her shirt so that her dark breast

bulged out.

“To the pillar with her!” cried Garnitter, and the three

students dragged her there in spite of biting and shrieking, and

bound her by body and legs next to the dead Haymon, so that

they could remain in silent and terrible company. For we took

the lantern with us and left the room with its sweetish haze of

blood, leaving only the candle burning as a death light for the

deceased. As we stood in the corridor, we heard the shrill

screams of the tied up woman.

And I must confess it: I took pity on her, because I felt

that it was not only her fault that she had to become like this.

Surely an evil fate had clawed at her from childhood; an

unguarded youth, instincts unleashed at an early age, abuse,

which one with her child body already suffered, poverty,

misery and lack of love did a terrible work on her. Was I

allowed to judge, when I opened the abysses of my own soul?

But as clever as the three students were, and as good as the

heart of one or the other might be, at this hour and in view of

the poor dead they would have looked at me with disgust if my

thoughts had become spoken aloud, and I would not have

helped anyone. So I kept silent and mourned in silence how

wrong people’s customs are, and how thousands and thousands

of children grow up without any care. And not only the brood

of the poor people –. How had it been with myself?

Leave a comment