The Rebirth of Melchior Dronte by Paul Busson and translated by Joe E Bandel

I looked around the distinguished room in which I was kept

waiting, and looked closely at the only picture, a man with

olive-brown, finely chiseled features, dark, sad eyes, of rather

unattractive facial formation, wearing a canary yellow uniform

with red lapels and under the coat, which was open, a black

breastplate. Then the maid reappeared, lifted the curtain and

asked me to enter with a curtsy.

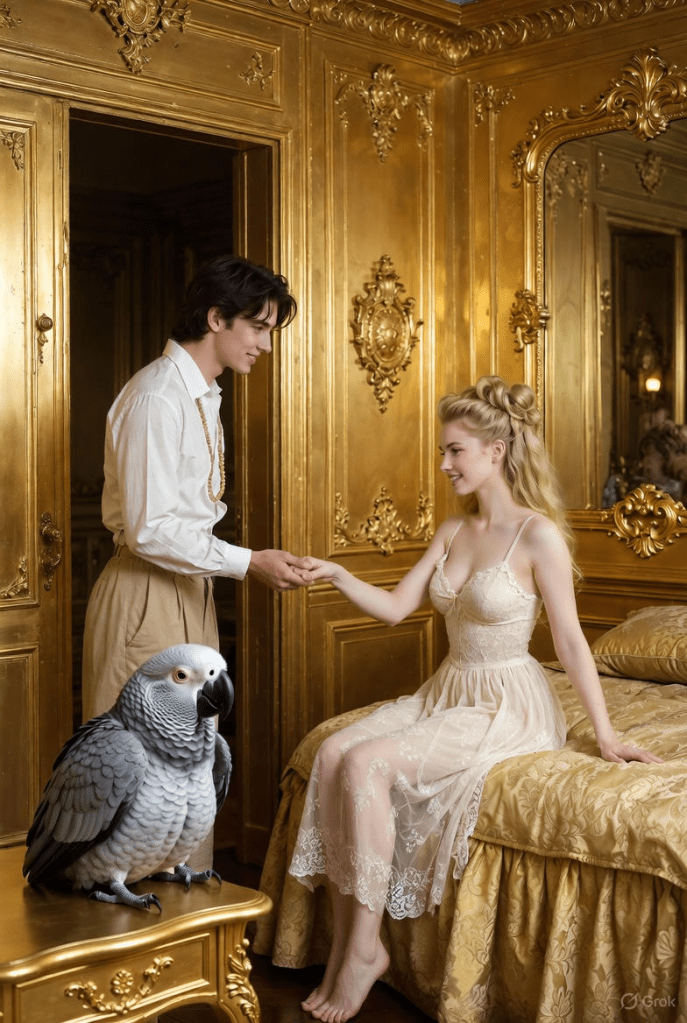

I entered a boudoir entirely in gleaming gold with

precious furniture and a brocade-covered resting bed, on which

Laurette half sat, half lay. She smilingly held her hand out to

me from a cloud of lace and thin silk, smiling, and I was again

struck anew by the unusual charm that her pretty, rosy face

radiated under the artful coiffure. But while I stared at her, not

at all to her displeasure, enraptured, that disgusting, shrill

laughter sounded close to us, and only then I noticed a chubby,

bald-headed parrot of gray color, from whose crooked beak

came the laughter.

If my whole mind had not been filled with the image of

that sweet child’s face and the reddish-gold hair, I would hardly

have felt at ease in the presence of this blossomed woman, who

had stirred my first emotions of love. I felt that I could not have

restrained myself for long, and all the more so because Laurette,

with consummate art, soon showed me a part of her perfectly

beautiful breast, soon the noble shape of a leg or the curve of

her classic arm. Nevertheless, I could not resist the desire to

remind the distinguished lady of those days, when she was still

called Lorle and had kissed me in the honeysuckle arbor behind

her father’s house. But she slipped away from me in a playful

mastery of the conversation, and thus forced me to respect the

boundaries she wished to keep. Yes, when I, fired by my

blissful memories, dared to touch her bare arm with my hand,

she struck me on my fingers and pointed with peculiar, even

serious, significance at the parrot, who was entertaining

himself by wiping his beak on the silver perch.

“Take care, my all too friendly cavalier, beware of this

bird,” she said softly, as if she were afraid that the ruffled beast

might be listening. “Apollonius does not like it when one

caresses me in his presence. Besides, my little finger tells me,

dear Baron, that you have not come to court me, but that you

have called on my willingness to serve you in some other way.”

“I cannot deny it,” I replied, somewhat affected, although

it seems unclear to me from where you, my dear Laurette, have

received such wisdom.”

“Ei!” she laughed, “Don’t I have my soothsayer and at

the same time protector and guardian next to me?” and less

loudly she added:

“It can be called a true good fortune, that the good

Apollonius is becoming somewhat hard of hearing and is no

longer able to overhear all that is spoken.”

The fact that she lowered her voice seemed indeed to

disgust the bird. He rolled his ball-eyes, stepped from one foot

to the other, and struck the cage bar with his beak, so that it

rang.

“Louder!” he cried.

“You see?” said Laurette, glancing shyly at him. “He’s in

a bad mood today.”

“He looks like an old Hebrew, your Apollonius,” I said

aloud. “It is believed that animals of his species live to be over

a hundred years old.”

“Hihihi! Hehehe! I’m an animal?” cried the bird. “A

hundred years! Imbecile!”

“What do you mean, he speaks French?” I turned to the

beautiful one.

“He speaks all languages,” whispered Laurette.

“Take care! He guards me, tells everything to the Spanish

envoy – whose mistress I am,” she added hesitantly, her cheeks

flushing slightly. “But Apollonius also bears witness to events

and is able to see into the future.”

Now I knew who the pimp was to whom she owed her

well-being, and so naturally a faint feeling of jealousy would

have arisen at this discovery. Not being of a jealous nature, I

felt nothing of the kind. Nevertheless, I felt sadness and

remorse that this once pure and benign child through my fault

had been taken from the peaceful and safe shelter of her

parents’ home to the glittering and uncertain splendor of a life

based only on lust.

At the same time, however, I clearly recognized that her

restraint towards me was not due to gratitude towards a present

friend and lover, but rather the fear of the treacherous gossip of

the feathered fowl to which she obviously attributed intellect

and human-like malice.

That through such thoughts the extremely ugly, bald-

headed animal became even more repugnant and hated by me

than already at the first sight, is understandable. I was tempted

to interact with the chattering bird. Or at least to check in every

way, to what extent Laurette’s description about his intelligence

was justified. How could this small, round bird’s head, behind

these rigid, rolling eyes be anything different from that of other

animals?

The repeating and coincidentally making sense of learned

words and randomly putting together learned words might be

suitable to cause strange, astonishing effects. But I could not

and did not believe in a human-like thinking ability. The only

thing I understood was Laurette’s caution to speak softly, so

that the hard-of-hearing bird would not parrot them back at

inopportune times. I myself had heard a story, in which a

starling, also a talking animal, had betrayed his mistress by

singing in front of her husband in the most melting tones the

first name of a young gentleman, who had been suspected for a

long time of being the favored lover of the housewife. Without

waiting for Laurette’s warm gesture, I turned to the parrot,

looked at him and said:

“Well, Apollonius, if you are really so clever as you are,

tell me who won the most money the day before yesterday at

the Pharaoh’s?”

The bird ruffled its feathers, twisted its eyeballs in a

ghastly way, chuckled a few times, and then cackled:

“Defunctus” – the dead one. I looked at him, unable to

speak a word.

“I beg you, Melchior, let him go,” said Laurette quickly

and quietly, and in her gaze there was fear. Then she said loudly,

“Baron, don’t tease Apollonius, or he’ll tell me the nastiest

things that deprive me of sleep at night.

“It was I who won, infernal beast!” I cried, and pulled

myself together.

The gray one laughed and said with his head bent

forward, eyeing me maliciously:

“Donum grati defunctil”-a gift from the grateful dead.

“Why don’t you turn the collar on such vicious vermin?”

I angrily prodded. “Give him some peach pits and get some

peace with it.”

She shook her head.

“He eats no poison, fair Herr! Little killer! Little

murderer!” chuckled Apollonius and flapped his wings.

“Perhaps you have murdered yourself, chewy, disgraceful

beast!” I screamed and shook my fist at him. “Perhaps you are

a soul damned by God and must now repent in the form of an

animal!”

There came a heavy, almost human sigh from the bar, a

groan from a tortured chest. The parrot looked at me with a

fearful and horribly desolate look, and hung its head. Slowly he

pulled the nictitating skin over his eyes, and with an inner

tremor I looked – by God in heaven! -, I saw two tears dripped

from the eyes of the animal. But this lasted only a moment,

because immediately after that he stared at me with such

appalling insolence that I became hot and cold and my rising of

pity quickly disappeared. But when I saw the troubled face of

the beautiful Laurette, I thought how naughty and disturbing

for her peace my behavior must have seemed to her, and to

rectify my mistake, I decided to turn the matter into a joke. I

bowed therefore with ironic politeness before the animal and

said in a cheerful tone:

“Do not be angry with me, venerable Apollonius, I did

not mean to offend your wisdom. I am now converted and no

longer doubt in your wonderful gift to see the past and the

future. Would it not be possible to make friends with you, king

of all parrots?”

The feathered one shook with laughter, clucked his beak

and whistled. Then he moved his head quite distinctly, after

human style, violently denying, back and forth.

“So we can’t be friends?” I continued and winked at

Laurette. “I would have liked to ask a question – about a

hunchback I’m looking for -.”

My question was for Laurette, of course, and I was about

to explain myself further, when it came buzzing from the bar:

“Dottore Postremo.”

“What do you want with him?” said Laurette, in

astonishment.

“Do you know him?” I asked, unable to conceal my

excitement. A deep blush passed over her face.

“As it happens –” she replied sheepishly.

“What is it about him?”

“He’s an Italian doctor — a lot of women go to see him

who wish to remove the unpleasant consequences of a few

pleasant hours. He has a reputation, and the courts have often

dealt with him. But nothing could ever be proved. – But you

must not think, Baron, that I might -“

I laughed politely, “How could I, beautiful Laurette?”

“He is said, by the way, to have a very beautiful foster-

daughter or niece,” she went on, looking at me lurkingly. “A

girl who has hardly blossomed. He lives in the house called

Zum Fassel.”

She lowered her eyes and looked at me from under her

lids.

“Be careful! The man is capable of anything!”

“You are mistaken, Laurette,” I lied. “It’s not a question

of adventures.”

Leave a comment