Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

He didn’t move. Again she stood up, ran to the table and came

back. She blew quickly on his left breast, then once more and waited,

listening to his breathing. Then he felt something cold and sharp slice

through his skin and realized it was a knife.

“Now she will thrust it,” he thought.

But that didn’t seem painful to him. It seemed sweet and even

good. He didn’t move and waited quietly for the quick thrust that

would open his heart. She cut slowly and lightly. Not very deep–but

deep enough that his hot blood welled up. He heard her quick breath,

opened his eyelids a little and looked up at her. Her lips were half-

open, the tip of her little tongue greedily pushed itself out between her

even teeth. Her small white breasts raised themselves quickly and an

insane fire shone out of her staring green eyes.

Then suddenly she threw herself over him, pressed her mouth to

the open wound, drank–drank. He lay there quietly, felt how the blood

flowed from his heart. It seemed to him as if she was drinking him

dry, sucking all of his blood, not leaving him a single drop.

And she drank–drank–through an eternity she drank–

Finally she raised her head. He saw how she glowed, her cheeks

shone red in the moonlight, and little drops of sweat pearled on her

forehead. With caressing fingers she once more tasted the red

refreshment from the exhausted well, then lightly pressed a few light

kisses on it, turned and looked with staring eyes into the moon–

There was something that pulled her. She stood up, went with

heavy steps to the window, climbed onto a chair, and set one foot on

the windowsill–awash with silvery moonlight.

Then, as if with sudden resolve, she climbed down again, didn’t

look to the right or to the left, glided straight through the room.

“I’m coming,” she whispered. “I’m coming.”

She opened the door and went out.

He lay there quietly for awhile listening to the steps of the

sleepwalker until they lost themselves somewhere in some distant

room. Then he stood up, put on his socks and shoes and grabbed his

robe. He was happy that she was gone. Now he could get a little sleep.

He had to leave, leave now – before she came back.

He crossed the hall and headed toward his room, then heard her

footsteps and pressed himself tightly into a doorway. But it was a

black figure, Frieda Gontram in her garb of mourning. She carried a

lit candle in her hand as she always did on her nightly strolls despite

the light of the full moon.

He saw her pale, distorted features, the hard lines that crossed

her nose, her thin pinched mouth, and her frightened, averted eyes.

“She was possessed,” he thought, “possessed just like he was.”

For a moment he considered speaking to her, to find out if–if

perhaps–But he shook his head, no, no. It wouldn’t help. She blocked

the way to his room, so he decided to go across to the library and lay

down there on the divan. He sneaked down the stairs, came to the

house door, slid back the bolt and unhooked the chain. Then he

quietly slipped outside and went out across the courtyard.

The Iron Gate stood wide open as if it were day. That surprised

him and he went through it out onto the street. The niche of the Saint

lay in deep shadows but the white stone statue shown brighter than

usual. Many flowers lay at his feet. Four, five little lanterns burned

between them and it seemed to him as if those little flames the people

brought, which they called eternal lamps, wanted to do battle against

the light of the moon.

“Paltry little lanterns,” he murmured.

But they helped him, were like a protection against the cruel,

unfathomable forces of nature. He felt safe in the shadows near the

Saint where the moon’s own light didn’t penetrate, where the Saint’s

own fires burned. He looked up at the hard features of the statue and it

seemed to him as if they lived in the flickering light of the lanterns. It

seemed as if the Saint extended himself, grew taller, and looked

proudly out to where the moon was shining. Then he sang, lightly

humming as he had many years ago, but this time ardently, almost

fervently.

John of Nepomuk

Protector against floods

Protect me from love!

Let it strike another.

Leave me in earthly peace

John of Nepomuk

Protect me from love.

Then he went back through the gate and across the courtyard.

The old coachman sat on the stone bench in front of the stables. He

saw him raise his arm and wave to him and he hurried across the

flagstones.

“What is it old man?” he whispered.

Froitsheim didn’t answer, just raised his hand, pointing upward

with his short pipe.

“What?” he asked. “Where?”

But then he saw. On the high roof of the mansion a slender,

naked boy was walking, quietly and confidently. It was Alraune. Her

eyes were wide open, looking upward, high above at the full moon.

He saw her lips move, saw how she reached her arms up into the

starry night. It was like a request, like a burning desire.

She kept moving, first on the ridge of the roof, then walking

along the eaves, step by step. She would fall, was going to fall! A

sudden fear seized him, his lips opened to warn her, to call out to her.

“Alr–”

But he stifled the cry. To warn her, to call her name–that would

mean her death! She was asleep, was safe–as long as she slept and

wandered in her sleep. But if he cried out to her, if she woke up–then,

then she would fall down!

Something inside him demanded, “Call out! Then you will be

saved. Just one little word, just her name–Alraune! You carry her life

on the tip of your tongue and your own as well! Call out! Call out!”

His teeth clenched together, his eyes closed; he clasped his hands

tightly together. But he sensed that it had to happen now, right now.

There was no going back; he had to do it! All his thoughts fused

together forming themselves into one long, sharp, murderous dagger,

“Alraune–”

Then a clear, shrill, wild and despairing cry sounded out through

the night–“Alraune–Alraune!”

He tore his eyes open, stared upward. He saw how she let her

raised arms drop, how a sudden shudder went through her limbs, how

she turned and looked back terrified at the large black figure that crept

out of the dormer window. He saw how Frieda Gontram opened her

arms wide and stumbled forward–heard once more her frightened cry,

“Alraune”.

Then he saw nothing more. A whirling fog covered his eyes; he

only heard a hollow thud and then a second one right after it. Then he

heard a weak, clear cry, only one. The old coachman grabbed his arm

and pulled him up. He swayed, almost fell–then sprang up and ran

with quick steps across the courtyard, toward the house.

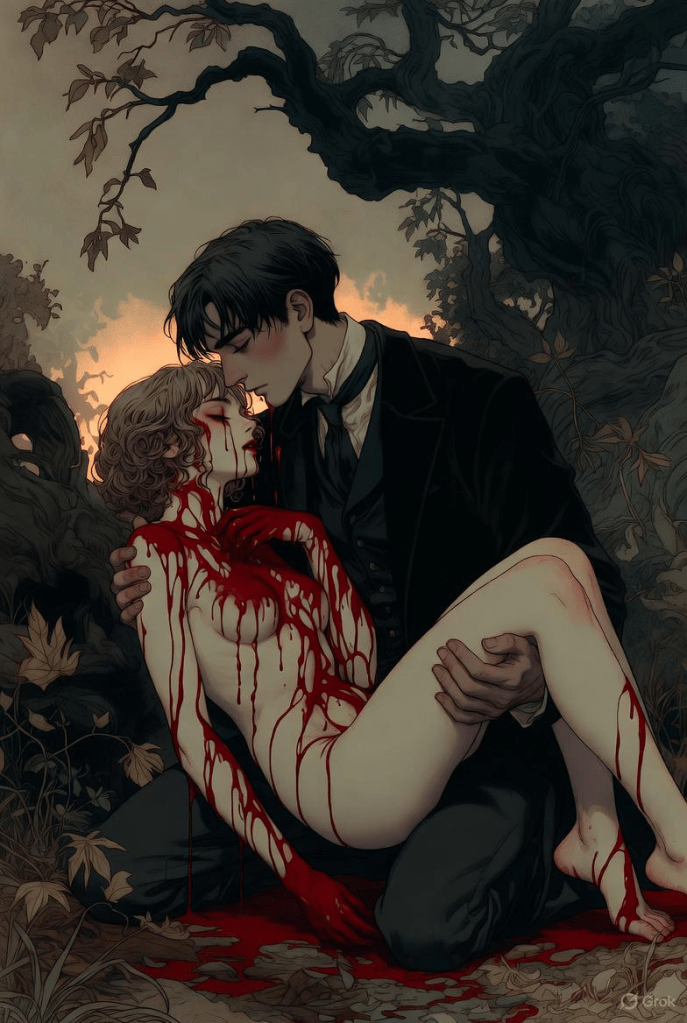

He knelt at her side, cradled her sweet body in his arms. Blood,

so much blood covered the short curls. He laid his ear to her heart and

heard a faint beating.

“She still lives,” he whispered. “Oh, she still lives.”

He kissed her pale forehead. He looked over to the side where

the old coachman was examining Frieda Gontram. He saw him shake

his head and stand up with difficulty.

“Her neck is broken,” he said.

What was that to him? Alraune still lived–she lived.

“Come old man,” he cried. “We will carry her inside.”

He raised her shoulders a little–then she opened her eyes, but she

didn’t recognize him.

“I’m coming,” she whispered. “I’m coming–”

Then her head fell back–

He sprang up. His sudden, raging and wild scream echoed from

the houses and flowed with many voices across the garden.

“Alraune, Alraune! It was me–I did it!”

The old coachman laid a gnarled hand on his shoulder and shook

his head.

“No, young Master,” he said. “Fräulein Gontram called out to

her.”

He laughed shrilly, “But I wanted to.”

The old face became dark, his voice rang harshly, “I wanted to.”

The servants came out of their houses, came with lights and with

noise, screaming and talking until they filled the entire courtyard.

Staggering like a drunk he swayed toward the house, supporting

himself on the old man’s arm.

“I want to go home,” he whispered. “Mother is waiting.”

Leave a comment