Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

Chapter Thirteen

Mentions how Princess Wolkonski told Alraune the truth.

LEGAL Councilor Gontram wrote the princess, who was in

Naulhiem undergoing medical treatment. He described the

situation to her. It took some time until she finally

understood what it was really all about.

Frieda Gontram, herself, took great pains to make sure the

princess comprehended everything. At first she only laughed, then she

became thoughtful, and toward the end she lamented and screamed.

When her daughter entered the room she threw her arms around her

neck wailing.

“Poor child,” she howled. “We are beggars. We will be living on

the streets!”

Then she poured heaps of caustic Eastern wrath over his dead

Excellency, sparing no obscene swear words.

“It’s not entirely that bad,” Frieda objected. “You will still have

your villa in Bonn and your little castle on the Rhine, also the

proceeds from your Hungarian vineyards. Then Olga will have her

Russian pension and–”

“One can’t live on that!” the old princess interrupted. “We will

starve to death!”

“We must try to change the Fräulein’s mind,” Frieda said, “like

father advises us!”

“He is an ass,” she cried. “An old scoundrel! He is in league with

the Privy Councilor, who has stolen from us! It was only through him

that I ever met that ugly swindler.”

She thought that all men were imposters, cheats and scoundrels.

She had still never met one that was any different. Take Olga’s

husband for example, that clean cut Count Abrantes–Hadn’t he

carried on the entire time with dirty music hall women, taking all of

her money that he could? Now he was living with a circus bareback

rider because the Privy Councilor had put his thumb down and

refused to give him any more–

“In that, his Excellency did do some good!” said the countess.

“Good!” screamed her mother–as if it didn’t matter who had

stolen the money!

“They are swine, the one just as much as the other.”

But she did see that they had to make an attempt. She wanted to

go herself, yet the other two talked her out of it. If she went there she

would certainly not achieve much more than the gentlemen from the

bank.

They had to proceed very diplomatically, declared Frieda, take

into consideration the moods and caprices of the Fräulein. She would

go by herself, that would be best. Olga thought it would be even better

if she went. The old princess objected, but Frieda declared it would

certainly not be very good if she interrupted her medical treatments

and got too excited. She could see that.

So both friends agreed and traveled together. The princess stayed

at the spa, but was not idle. She went to the priest, ordered a hundred

masses for the poor soul of the Privy Councilor.

“That is the Christian thing to do,” she thought and since her

deceased husband was Russian Orthodox, she went to the Russian

chapel and paid that priest for a hundred masses as well. That calmed

her very much.

At one point she thought it would scarcely be of any use because

his Excellency had been protestant and a free thinker as well. But then

it would count as an especially good work in her favor.

“Bless them that curse you.” “Love your enemies.” “Do unto

others as you would have them do unto you.”

Oh, they must surely recognize such things up there, and twice a

day in her prayers, she spoke a special plea for his Excellency–with

very intense fervor. In this way she bribed the love of God.

Frank Braun received the two ladies at Lendenich, led them up to

the terrace and chatted with them about old times.

“Try your luck, children,” he said. “My talking was of no use!”

“What did she say to you?” asked Frieda Gontram.

“Not much,” he laughed. “She didn’t even listen to all of it. She

made a deep curtsy and declared with a devilish grin that she

completely treasured the high honor of my guardianship and would

not even consider ending it for the sake of the princess. She added

that she did not wish to speak of it again. Then she curtsied again,

even more deeply, even more respectfully–and she disappeared!”

“Haven’t you made a second attempt?” asked the countess.

“No, Olga,” he said. “I must now leave that to you–her look as

she left was so determined that I am solidly convinced all my

persuasive skills would be just as unfruitful as that of the other

gentlemen.”

He stood up, rang for the servant to bring some tea.

“By the way, you ladies just might have a chance,” he continued.

“A half hour after the Legal Councilor called giving notice of your

arrival I told my cousin that you would be coming and why. I was

afraid she would not receive you at all and in any case wanted you to

have a chance.

But I was wrong. She declared that you were both very welcome,

that for months now she has been in very active correspondence with

both of you–that is why–”

Frieda Gontram interrupted him.

“You wrote to her?” she cried sharply.

Countess Olga stammered, “I–I–have written her a couple of

times–to offer my condolences–and–and–”

“You lie!” Frieda cried.

The countess sprang up at that, “What about you? Don’t you

write her? I knew that you were doing it, every two days you write to

her. That’s why you are always alone in your room for so long.”

“You’ve had the chambermaid spy on me!” Frieda accused.

The glares of the two friends crossed each other, throwing a

burning hate that was sharper than words. They understood each other

completely.

For the first time the countess felt that she was not going to do

what her friend requested and Frieda Gontram sensed this first

resistance against her authority.

But they were bound through long years of their lives, through so

many common memories–that it couldn’t be extinguished in an

instant.

Frank Braun noticed right away.

“I’m disturbing you,” he said. “By the way, Alraune will be

coming soon. She just wanted to get ready.”

He went to the garden stairs, then gave his regards.

“I will see you ladies again later.”

The friends said nothing. Olga sat in a cane easy chair. Frieda

paced up and down with large strides. Then she stopped and stood

right in front of her friend.

“Listen Olga,” she said softly. “I have always helped you, when

we were serious and when we were playing, through all of your

adventures and love affairs. Isn’t that true?”

The countess nodded, “Yes, but I have done exactly the same

thing for you, not any less.”

“As well as you could,” spoke Frieda Gontram. “I will gladly

admit it–we want to remain friends then?”

“Certainly!” cried Countess Olga. “Only–only–I’m not asking

that much!”

“What are you asking?” inquired the other.

She answered, “Don’t put any obstacles in my way!”

“Obstacles?” Frieda returned. “Obstacles to what? Each of us

should try our luck–like I already told you at the Candlemas ball!”

“No,” insisted the countess. “I don’t want to compete any more.

I’ve competed with you so often–and always drawn the short straw. It

is unequal–for that reason you will withdraw this time, if you love

me.”

“Why is it unequal?” cried Frieda Gontram. “It’s even in your

favor–you are more beautiful!”

“Yes,” her friend replied. “But that is nothing. You are more

clever and I have often learned through experience how that is worth

more–in these things.”

Frieda Gontram took her hand.

“Come Olga, she said, flattering her. “Be reasonable. We are not

here just because of our feelings–listen to me. If I can succeed in

getting the little Fräulein to change her mind, if I can save those

millions for you and your mother–will you then give me a free hand?–

Go into the garden, leave me alone with her.”

Large tears marched out of the eyes of the countess.

“I can’t,” she whispered. “Let me speak with her. I will gladly

give you the money–this is only a sudden whim of yours.”

Frieda sighed out loud, threw herself into the chaise lounge, sank

her slender fingers deeply into the silk cushions.

“A whim?–Do you believe I would make such a fuss over a

whim?–With me, I’m afraid, it appears to be not much different than

it is with you!”

Her features appeared rigid; her clear eyes stared out into

emptiness.

Olga looked at her, sprang up, knelt down in front of her friend,

who bowed her head down low over her. Their hands found each

other and they tightly pressed themselves against each other, their

tears quietly mingled together.

“What should we do?” asked the Countess.

“Withdraw!” said Frieda Gontram sharply. “Withdraw–both of

us–let what happens, happen!”

Countess Olga nodded, pressing herself tightly against her friend.

“Stand up,” whispered the other. “Here she comes. Quick, dry

your tears–here, take my handkerchief.”

Olga obeyed, went across to the other side.

But Alraune ten Brinken saw very clearly what had just

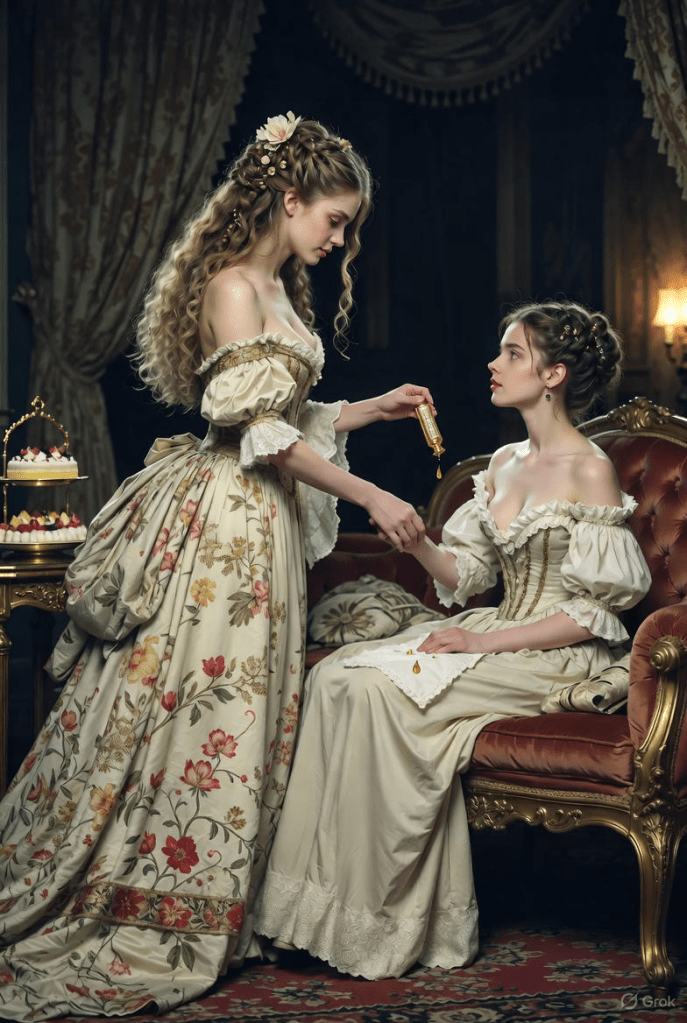

happened. She stood in the large doorway, in black tights like the

merry prince from “The Fledermaus”. She gave a short bow, greeted

them and kissed the hands of the ladies.

“Don’t cry, it makes your beautiful little eyes cloudy.”

She clapped her hands together, called for the servant to bring

some champagne. She, herself, filled the goblets, handed them to the

ladies and urged them to drink.

“It is the custom here,” she trilled. “Each to their own taste.”

She led Countess Olga to a chaise lounge and caressed her entire

arm. Then she sat down next to Frieda and gave her a slow, smiling

glance. She stayed in her role, offered cakes and petit fours, poured

drops of Peáu d’Espagne out of her golden vial onto the ladies

handkerchiefs.

Then she began, “Yes, it’s true. It is very sad that I can’t help

you. I’m so sorry.”

Frieda Gontram straightened up, opened her lips with great

difficulty.

“And why not?” she asked.

“I have no reason at all,” answered Alraune. “Really none at

all!–I simply don’t want to–that is all.”

She turned to the Countess, “Do you believe your Mama will

suffer very much because of that?”

She stressed the “very”–and in doing so, her voice twittered

sweet and cruel at the same time like a swallow on the hunt. The

countess trembled under her gaze.

“Oh, no!” she said. “Not that much.

And she repeated Frieda’s words–

“She will still have her villa in Bonn and the little castle on the

Rhine. Then there were the proceeds from the Hungarian vineyards. I

also have my Russian pension and–”

She stopped, didn’t know any more. She had no concept of her

financial standing, scarcely knew what money was, only that you

could go into beautiful shops and buy things with it, hats and other

pretty things. There would be more than enough to do that.

Leave a comment