Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

The guests pressed to the edges, those in back climbed up on

chairs and tables. They watched, breathless.

“I congratulate you, your Excellency,” murmured Princess

Wolkonski.

The Privy Councilor replied, “Thank you, your Highness. You

see that our efforts have not been entirely in vain.”

They changed directions, the Chevalier led his Lady diagonally

across the hall, and Rosalinde opened her eyes wide, throwing quiet,

astonished glances at the crowd surrounding them.

“Shakespeare would kneel if he saw this Rosalinde,” declared the

professor of literature.

But at the next table little Manasse barked from his chair down to

Legal Councilor Gontram.

“Stand up and look just this once, Herr Colleague! Look at that!

Your boy looks just like your departed wife–exactly like her!”

The old Legal Councilor remained sitting quietly, sampling a

new bottle of Urziger Auslese.

“I can’t especially remember any more how she looked,” he

opined indifferently.

Oh, he remembered her well, but what did that have to do with

other people?

The couple danced, down through the hall and back. Rosalinde’s

white shoulders rose and fell faster, her cheeks grew flushed–but the

Chevalier smiled under his powder and remained equally graceful,

equally certain, confident and nimble.

Countess Olga tore the red carnations out of her hair and threw

them at the couple. The Chevalier de Maupin caught one in the air,

pressed it to his lips and blew her a kiss. Then all the others grabbed

after colorful flowers, taking them out of vases on the tables, tearing

them from clothing, loosening them from their hair, and under a

shower of flowers the couple waltzed to the left around the hall

carried by the sounds of “Roses of the South”.

The orchestra started over and over again. The musicians, dulled

and over tired from nightly playing, appeared to wake up, leaning

over the balustrade of the balcony and looking down. The baton of the

conductor flew faster, hotter rushed the bows of the violinists and in

deep silence the untiring couple, Rosalinde and the Chevalier de

Maupin, floated through a sea of roses, colors and sounds.

Then the conductor stopped the music. Then it broke loose. The

Baron von Platten, Colonel of the 28th cried out with his stentorian

voice down from the gallery:

“A cheer for the couple! A cheer for Fräulein ten Brinken! A

cheer for Rosalinde!”

The glasses clinked and people shouted and yelled, pressing onto

the dance floor, surrounding the couple, almost crushing them.

Two fraternity boys from Rhenania carried in a mighty basket

full of red roses they had purchased downtown somewhere from a

flower woman. A couple Hussar officers brought champagne. Alraune

only sipped, but Wolf Gontram–overheated, red-hot and thirsty,

guzzled the cool drink greedily, one goblet after another.

Alraune pulled him away, breaking a path through the crowd.

The red executioner sat in the middle of the hall. He stuck out his long

neck, held out his axe to her with both hands.

“I have no flowers,” he cried. “I myself am a red rose. Pluck

me!”

Alraune left him sitting, led her lady further, past the tables

under the gallery and into the conservatory. She looked around her. It

was no less full of people and all of them were waving and calling out

to them. Then she saw a little door behind a heavy curtain that led out

to a balcony.

“Oh, this is good!” she cried. “Come with Wölfchen!”

She pulled back the curtain, turned the key, and pressed down on

the latch. But five coarse fingers rested on her arm.

“What do you want there?” cried a harsh voice.

She turned around. It was Attorney Manasse in his black hooded

robe and mask.

“What do you want outside?” he repeated.

She shook off his ugly hand.

“What is it to you?” she answered. “We just want to get a breath

of fresh air.”

He nodded vigorously, “That’s just what I thought, exactly why I

followed you over here! But you won’t do it, will not do it!”

Fräulein ten Brinken straightened up, looked at him haughtily.

“And why shouldn’t I do it? Perhaps you would like to stop us?”

He involuntarily sagged under her glance, but didn’t give up.

“Yes, I will stop you, I will! Don’t you understand that this is

madness? You are both over heated, almost drenched in sweat–and

you want to go out onto the balcony where it is twelve degrees below

zero?”

“We are going,” insisted Alraune.

“Then go,” he barked. “It doesn’t matter to me what you do

Fräulein–I will only stop the boy, Wolf Gontram, him alone.”

Alraune measured him from head to foot. She pulled the key out

of the lock, opened the door wide.

“Well then,” she said.

She stepped outside onto the balcony, raised her hand and

beckoned to her Rosalinde.

“Will you come out into the winter night with me?” she cried.

“Or will you stay inside the hall?”

Wolf Gontram pushed the attorney to the side, stepped quickly

through the door. Little Manasse grabbed at him, clamped tightly onto

his arm. But the boy pushed him back again, silently, so that he fell

awkwardly against the curtain.

“Don’t go Wolf!” screamed the attorney. “Don’t go!”

He looked wretched, his hoarse voice broke.

But Alraune laughed out loud, “Adieu, faithful Eckart! Stay

pretty in there and guard our audience!”

She slammed the door in his face, stuck the key in the lock and

turned it twice. The little attorney tried to see through the frosted

window. He tore at the latch and in a rage stamped both feet on the

floor. Then he slowly calmed himself, came out from behind the

curtain and stepped back into the hall.

“So it is fate,” he growled.

He bit his strong, tangled teeth together, went back to his

Excellency’s table, let himself fall heavily into a chair.

“What’s wrong, Herr Manasse?” asked Frieda Gontram. “You

look like seven days of rainy weather!”

“Nothing,” he barked. “Absolutely nothing–by the way, your

brother is an ass! Herr Colleague, don’t drink all of that alone! Save

some of it for me!”

The Legal Councilor poured his glass full.

But Frieda Gontram said quite convinced, “Yes, I believe that

too. He is an ass.”

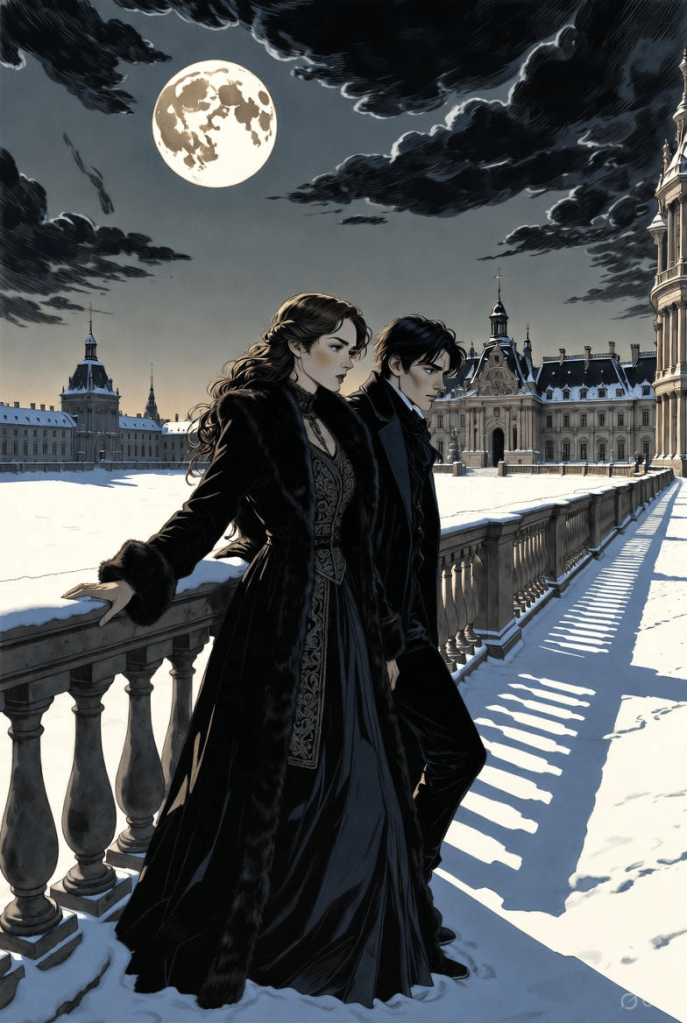

The two walked through the snow, leaned over the balustrade,

Rosalinde and the Chevalier de Maupin. The full moon fell over the

wide street, threw its sweet light on the baroque shape of the

university, then the old palace of the Archbishop. It played on the

wide white expanses down below, throwing fantastic shadows

diagonally over the sidewalk.

Wolf Gontram drank in the icy air.

“That is beautiful,” he whispered, waving with his hand down at

the white street where there was not the slightest sound to disturb the

deep silence.

But Alraune ten Brinken was looking at him, saw how his white

shoulders glowed in the moonlight, saw his large deep eyes shining

like opals.

“You are beautiful,” she said to him. “You are more beautiful

than the moonlit night.”

He let go of the stone balustrade, reached out for her and

embraced her.

“Alraune,” he cried. “Alraune.”

She endured this for a moment, then freed herself, and patted

him lightly on the hand.

“No,” she laughed, “No! You are Rosalinde–and I am the boy, so

I will court you.”

She looked around, grabbed a chair out of the corner, dragged it

over, beat off the snow with her sword-cane.

“Here, sit down my beautiful Fräulein. Unfortunately you are a

little too tall for me! That’s better–now we are just right!”

She bowed gracefully, then went down on one knee.

“Rosalinde,” she chirped. “Rosalinde! Permit a knight errant to

steal a kiss–”

“Alraune,” he began.

But she sprang up, clapped her hand over his lips. “You must say

‘Mein Herr!’” she cried.

“Now then, will you permit me to steal a kiss Rosalinde?”

“Yes, Mein Herr,” he stammered.

Then she stepped behind him, took his head in both arms and she

began, hesitated.

“First the ears,” she laughed, “the right and now the left, and the

cheeks, both of them–and your stupid nose that I have so often kissed.

Finally–lookout Rosalinde, your beautiful mouth.”

She bent lower, pressed her curly head against his shoulder under

his hat. But she pulled back again.

“No, no, beautiful maiden, leave your hands! They must rest

quietly in your lap.”

He laid his shivering hands on his knee and closed his eyes. Then

she kissed him, slowly and passionately. At the end her small teeth

sought his lip, bit it quickly so that heavy drops of red blood fell down

onto the snow.

She tore herself loose, stood in front of him, staring blankly at

the moon with wide-open eyes. A sudden chill seized her, threw a

shiver over her slender limbs.

“I’m freezing,” she whispered.

She raised one foot up and then the other.

“The stupid snow is everywhere inside my dance slippers!”

She pulled a slipper off and shook it out.

“Put my shoes on,” he cried. “They are bigger and warmer.”

He quickly slipped them off and let her step into them.

“Is that better?”

“Yes,” she laughed. “I feel good again. For that I will give you

another kiss, Rosalinde.”

And she kissed him again–and again she bit him. Then they both

laughed at how the moon lit up the red stains on the white ground.

“Do you love me, Wolf Gontram?” she asked.

He said, “I think of nothing else but you.”

She hesitated a moment, then asked again–“If I wanted it–would

you jump from the balcony?”

“Yes,” he said.

“Even from the roof?”

He nodded.

“Even from the tower of the Münster Cathedral?”

He nodded again.

“Would you do anything for me, Wölfchen?” she asked.

“Yes, Alraune,” he said, “if you loved me.”

She pursed her lips, rocked her hips lightly.

“I don’t know whether I love you,” she said slowly. “Would you

do it even if I didn’t love you?”

His gorgeous eyes that his mother had given him shone, shone

fuller and deeper than they had ever done and the moon above,

jealous of those eyes, hid from them, concealing itself behind the

cathedral tower.

“Yes,” said the boy. “Yes, even then.”

She sat on his lap, wrapped her arms around his neck.

“For that, Rosalinde–for that I will kiss you for a third time.”

And she kissed him again, still longer and more passionately and

she bit him–more wildly and deeply. But they couldn’t see the heavy

drops in the snow any more because the jealous moon had hidden its

silver torch.

“Come,” she whispered. “Come, we must go!”

They exchanged shoes, beat the snow off their clothing, opened

the door and stepped back inside, slipped behind the curtain and into

the hall. The arc-lamps overhead were glaring; the hot and sticky air

stifled them.

Wolf Gontram staggered as he let go of the curtain, grasping

quickly at his chest with both hands.

She noticed it. “Wölfchen?” she cried.

He said, “It’s nothing, nothing at all–just a twinge! But it’s all

right now.”

Hand in hand they walked through the hall.

Wolf Gontram didn’t come into the office the next day, never got

out of bed, lay in a raging fever. He lay like that for nine days. He was

often delirious, called out her name–but not once during this time did

he come back to consciousness.

Then he died. It was pneumonia. They buried him outside, in the

new cemetery.

Fräulein ten Brinken sent a large garland of full, dark roses.

Leave a comment