Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

Chapter Ten

Describes how Wolf Gontram was put into the ground because

of Alraune.

KARL Mohnen was not the only one around that time that

fell under the deceptive wheels of his Excellency’s

magnificent machine. The Privy Councilor completely took

over the large People’s Mortgage Bank, which had been

under his influence for a long time. At the same time he took

possession and control over the wide many-branched Silver Frost

Association that had their little savings banks in every little village

under the flag of the church.

That didn’t happen without sharp friction since many of the old

employees that had thought their positions permanent were reluctant

to cooperate with the new regime.

Attorney Manasse, together with Legal Councilor Gontram, legal

advisor for these transactions, acted in as many ways as possible to

soften the transition without hindering it. His Excellency’s lack of

regard made things severe enough and everything that did not appear

absolutely necessary to him was thrown away out of hand without

further thought. Using right dubious means he pushed to the side

other little district associations and banks that opposed him and

refused to submit to his control.

By now his superior might extended far into the industrial district

as well–everything that had to do with the earth–coal, metals, mineral

water, water works, real estate, buildings, agriculture, road making,

dams, canals–everything in the Rhineland more or less depended on

him.

Since Alraune had come back into the house he handled things

with fewer scruples than ever. From the time he first became aware of

her influence on his success he showed no more regard to others, no

restraint or consideration.

In long pages in the leather volume he explained all of these

affairs. Evidently it gave him joy to speak of each new undertaking

that was of little value with almost no possibility of success–it was

only of these things that he would grab up–and finally attribute their

success to the creature that lived in his house.

From time to time he would solicit advice from her without

entrusting her with the particulars, asking only, “Should I do it?”

If she nodded, he did it and would drop it immediately if she

shook her head. The law had not appeared to exist anymore to the old

man for a long time now. Earlier he had spent long hours talking

things over with his attorneys, trying to find a way out, a loophole or

twist of phrase that would give him a back door. He had studied all

possible gaps in the law books, knew all kinds of tricks and whistles

that made outright evil deeds legally acceptable. It had been a long

time now since he had troubled himself with such evasions.

Trusting only on his power and his luck he broke the law many

times knowing full well that no judge would stand up with the

plaintiff to balance the scales. His lawsuits multiplied as well as the

complaints against him. Most were anonymous, including those the

authorities themselves entered against him.

But his connections extended as far into the government as they

did the church. He was on close terms with them both. His voice in

the provincial daily papers was decisive. The policies of the

ArchBishop’s palace in Cologne, which he supported, gave him even

greater backing. His influence went as far as Berlin where an

exceptionally meritorious medal was given to him at an unveiling of a

monument dedicated to the Kaiser. The hand of the All Highest

himself placed the medal around his neck and was documented

publicly.

Really, he had steered a good sum of money into the building of

the monument–but the city had paid dearly for the real estate on

which it stood when they were required to purchase it from him.

In addition to these were his title, his venerable age, his

acknowledged services to the sciences. What little public prosecutor

would want to press charges against him? A few times the Privy

Councilor himself pressed charges at some of these accusations. They

were seen as gross exaggerations and collapsed like soap bubbles.

In this way he nourished the skepticism of the authorities toward

his accusers. It went so far that in one case when a young assistant

judge was thoroughly convinced, clear as day, against his Excellency

and wanted to intervene, the District Attorney without even looking at

the records declared:

“Stupid stuff! Grumblers screaming–We know that! It would

only make us look like fools.”

In this case the grumbler was the provisional director of the

Wiesbaden Land Museum which had purchased all manner of

artifacts from the Privy Councilor. Now he felt defrauded and wanted

to publicly declaim him as a forger of antiquities.

The authorities didn’t take up the case but they did notify the

Privy Councilor who defended himself very well. He wrote his own

personal publication that was inserted into a special Sunday edition of

the “Cologne News”. The beautiful human-interest story carried the

title, “Taking care of our Museums”.

He didn’t go on about any of the accusations against him, but he

attacked his opponent viciously, destroyed him completely, placing

him as a know nothing and cretin. He didn’t stop until the poor

scholar lay unmoving on the floor. Then he pulled his strings, let his

wheels turn–after less than a month there was a different director in

the museum.

The head district attorney nodded in satisfaction when he read

the notice in the paper.

He brought the page over to the assistant judge and said, “Read

that, colleague! You can thank God that you asked me about it and

avoided such a fatal error.”

The assistant judge thanked him, but was not absolutely

convinced.

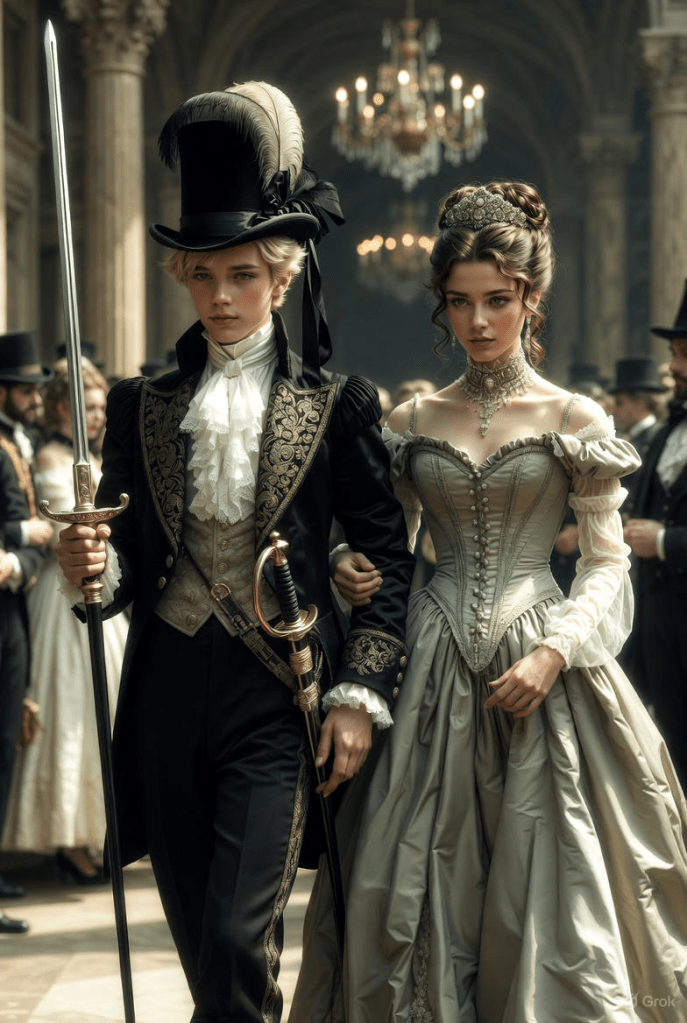

In early February on Candlemass all the sleighs and autos

traveled to “The Gathering”. It was the great Shrovetide Ball of the

community. The Royalty was there and around them circled anyone in

the city that wore uniforms or colored fraternity armbands and caps.

Professors circled there as well, along with those from the court,

the government, city officials, rich people, Councilors to the Chamber

of Commerce and wealthy industrialists.

Everyone was in costume. Only the declared chaperones were

allowed to dress as false Spaniards. The old gentleman himself had to

leave his dress suit at home and come in a black hooded robe and

cowl. Legal Councilor Gontram presided at his Excellency’s large

table. He knew the old wine cellar and understood it, the best vintages

and how to procure them.

Princess Wolkonski sat there with her daughter Olga, now

Countess Figueirea y Abrantes, and with Frieda Gontram. Both were

visiting her for the winter.

Then there was Attorney Manasse, a couple of private university

speakers, professors and even a few officers and of course the Privy

Counselor himself who had taken his little daughter out for her first

ball.

Alraune came dressed as Mademoiselle de Maupin wearing

boy’s clothes in the style of Beardsly’s famous illustrations. She had

torn through many wardrobes in the house of ten Brinken, stormed

through many old chests and trunks. She finally found them in a damp

cellar along with piles of beautiful Mechlin lace that an ancient

predecessor had placed there. It is certain the poor seamstress who

created them would have cried tears to see them treated like that.

This lacey women’s clothing that made up Alraune’s cheeky

costume netted still more fresh tears–she scolded the dressmaker that

could not get just the right fit to the capricious costume, the hair

dresser that Alraune beat because she couldn’t understand the exact

hair style Alraune wanted and who couldn’t lay the chi-chi’s just

right, and the little maid whom she impatiently poked with a large pin

while getting dressed.

Oh, it was a torture to turn Alraune into this girl of Gautier’s, in

the bizarre interpretation of the Englishman, Beardsly.

But when it was done, when the moody boy with his high sword-

cane strutted with graceful pomp through the hall, there were no eyes

that didn’t greedily follow him, no old ones or young ones, of either

men or women.

The Chevalier de Maupin shared his glory with Rosalinde.

Rosalinde, the one in the last scene–was Wolf Gontram, and never did

the stage see a more beautiful one. Not in Shakespeare’s time when

slender boys played the roles of his women. Not even later since

Margaret Hews, the beloved of Prince Rupert, was the first woman to

play the part of the beautiful maiden in “As You Like It”.

Alraune had the youth dressed and with infinite care had brought

him up to this point. She taught him how to walk, how to dance, how

to move his fan and even how he should smile.

And now, even as she appeared as a boy and yet a girl kissed by

Hermes as well as Aphrodite in her Beardsly costume; Wolf Gontram

embodied the character of his compatriot, Shakespeare, no less.

He was in a red evening gown and train brocaded with gold, a

beautiful girl, and yet a boy as well. Perhaps the old Privy Councilor

understood all of it, perhaps little Manasse, perhaps even Frieda

Gontram did a little as her quick look darted from one to the other.

Other than that it was certain that no one else did in that immense hall

of the Gathering in which heavy garlands of red roses hung from the

ceiling.

But everyone felt it, felt that here was something special, of

singular worth. Her Royal Highness sent her adjutant to fetch them

both and present them to her. She danced the first waltz with him,

playing the gentleman to Rosalinde, then as the lady with the

Chevalier de Maupin. She clapped her hands loudly during the minuet

when Théophile Gautier’s curly headed boy bowed and flirted with

Shakespeare’s sweet dream girl directly in front of her.

Her Royal Highness was an excellent dancer herself, was first at

the tennis courts and the best ice skater in the city. She would have

loved to dance through the entire night with only the two of them. But

the crowd wanted their share as well. So Mademoiselle de Maupin

and Rosalinde flew from one set of arms into another, soon pressing

into the muscular arms of young men, soon feeling the hot heaving

breasts of beautiful women.

Legal Councilor Gontram looked on indifferently. The Treves

punch bowl and its brewed contents interested him much more than

the success of his son. He attempted to tell Princess Wolkonski a long

story about a counterfeiter but her Highness wasn’t listening.

She shared the satisfaction and happy pride of his Excellency ten

Brinken, felt herself a participant in the creation and bringing into the

world of this creature, her Godchild, Alraune.

Only little Manasse was bad tempered enough, cursing and

muttering under his breath.

“You shouldn’t dance so much boy,” he hissed at Wolf. “Be

more careful of your lungs!”

But young Gontram didn’t hear him.

Countess Olga sprang up and flew out to Alraune.

“My handsome chevalier,” she whispered.

The boy dressed in lace answered, “Come here my little Tosca!”

He wheeled her around to the left and circled through the hall,

scarcely giving her time to breathe, brought her back to the table

breathless and kissed her full on the mouth.

Frieda Gontram danced with her brother, looking at him for a

long time with her intelligent gray eyes.

“It’s a shame that you are my brother,” she said.

He didn’t understand her at all.

“Why?” he asked.

She laughed, “Oh, you stupid boy! By the way, your answer

‘Why?’ is entirely correct. It shouldn’t make any difference at all

should it? It is only the last shred of those morals that our stupid

education has given us. Like putting lead weights in our virtuous

skirts to keep them long, stretched smooth and modest. That’s what it

is, my beautiful little brother!”

Leave a comment