Madame Bluebeard by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

“Oh,” Schiereisen resisted, “I can’t just,

unannounced…”

“Yes, you can,” Ruprecht laughed, “come on.” He

took Schiereisen’s arm, ushering him out.

Downstairs, Rotrehl and Rauß stepped out the

door. Rotrehl bowed stiffly; Rauß glared at Ruprecht,

his gaze a mix of scorn and fanatical hate.

Ruprecht untied his horse from the fence, walking

beside Schiereisen down the hill.

The village below began ringing noon. The sound

arched grandly, brazenly over the valley, rising into

the sunlight, fading among spring sky’s lamb-white

clouds. Again and again, it swelled upward, resonant

and brazen, filling the world.

“It’ll end,” Rauß said venomously. “All this—the

ringing, praying, processions, banners… until

workers’ battalions march, thundering over the earth,

and the proletariat sweeps away all that didn’t heed in

time. No capital, no titles, no ‘Herr von’… all must

go… him down there too…”

Rotrehl gave no reply, staring skyward, as if

chasing the newspaper slogans’ flutter.

“You, Krampulljon,” Rauß said, grabbing

Rotrehl’s collar, “don’t dawdle. Join us. You’re a

proletarian too, even with your little house. We must

stand against exploiters. Farmers are too dumb to see

it. Who do those cider-heads toil for? After taxes and

usurers’ interest, what’s left? Barely enough to live.

And the gentry fund church banners! In our time…

instead of pensions or hospitals… or roads… We’ll

make ‘em pay. That banner’ll cost ‘em dear.”

Rotrehl shook his Napoleonic head. “I’m not for

such things. Leave me out. I’m neither for banners

nor proletarians. I don’t belong here… my French

blood…”

“Keep your French blood,” Rauß roared, furious.

“Let it sour, your French blood… you… clown.” He

seemed ready to punch Rotrehl but thought better,

yanked his cap’s brim forward, spat left and right,

and stormed off.

Rotrehl stood petrified, unable to move. What was

this, when people disrespected even bloodlines?

Where was the world headed? He’d never faced such

a thing. Regaining himself, he fumbled for his pipe

with trembling hands, stuffed it, and lit it. After a few

puffs, he forgot to smoke, the pipe dangling limply

between his teeth…

Slowly, he entered his room, stood before

Napoleon’s lithograph, and searched its features

anxiously, fearing it had heard the blasphemy.

Frau Helmina had fun with the lunch guest

Ruprecht brought. She recognized the comical man

who’d leapt before her carriage from the woods. A

scholar straight from a caricature—ponderously

formal, his clumsy solemnity failing to hide his

insecurity. His meticulous shoe-cleaning before

entering a room was a spectacle. He clung to carpets,

dreading bare floors.

When introduced, Helmina slyly noted they’d

already met, making Schiereisen blush and stammer

apologies. She let him flounder, offering no help, her

smiling silence relentless. Ruprecht stepped in—he

didn’t want the man crushed. Something drew him to

this simple soul, a liking, a wish to connect with

someone he could talk to. Trust began to sprout.

At the table, Helmina watched her guest’s anxious

care to avoid blunders. He glanced left and right,

touching no utensil until he saw its use. Lorenz and

old Johann served. Lorenz kept his iron mask;

Johann, too well-bred, hid his recognition.

Schiereisen nodded awkwardly at Johann, unsure if

he should acknowledge the tie. A prime specimen,

Helmina thought.

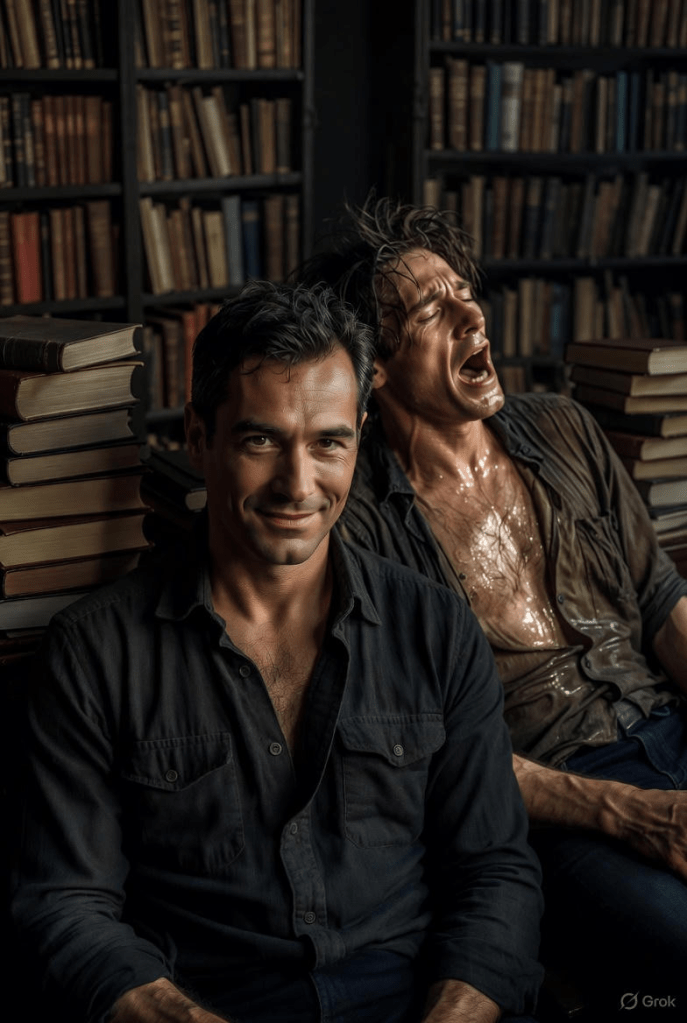

After the meal, Ruprecht showed the Celt scholar

his library, between the study and the Indian temple.

Schiereisen came alive, rifling books, climbing

ladders to upper shelves, rummaging eagerly, red-

faced, muttering a monologue more for himself than

Ruprecht. He splashed in tomes and folios like a fish

in water, visibly at ease.

Ruprecht watched, smiling. “Hope you find

something useful,” he said. “Come whenever you

like. Use the library freely. Take your time.”

After an hour, Schiereisen, sweat-soaked and

spent, collapsed onto a chair by a stacked pile of

books. “Yes—I must come often. There are splendid

old things here…”

“I believe Count Moreno laid the library’s

foundation. Some of his collection likely remains.”

“Is this the Moreno crest?” Schiereisen asked,

opening a dusty copperplate volume with a stamp on

its first page.

“Yes… Herr Dankwardt was keen on Indian

philosophy. That’s my interest too. I know the land

and try to understand it, though I’m just a dilettante.

Here’s the Indian temple he set up.”

Schiereisen followed Ruprecht into the adjacent

room, inspecting everything with polite attention, but

his heart wasn’t in it. It clung to ancient Celts,

leaving no room for other peoples. As Ruprecht

explained, animating painted landscapes and odd

artifacts with memories, Jana entered, reporting a

messenger from a distant farm with urgent news. His

gaze shifted from his master to the guest.

Ah, Schiereisen thought. The Malay, the Indian, as

they call him. He saved his master once. I’d know

what he knows. That look—like a wary dog, sizing up

anyone near. He’s guarding his lord.

Ruprecht excused himself for the pressing matter,

leaving with Jana. Schiereisen darted back to the

library, diving into his books. Dust swirled in small

clouds. He searched the shelves again. Earlier, behind

the hefty Theatrum Europaeum, he’d spotted a slim

booklet, the most vital of all. It outshone every

weighty Celtic tome. He’d nudged it out slightly to

find it later.

It was a manuscript, neatly bound in red leather,

adorned with baroque gold-pressed arabesques. The

first page held a watercolor view of Vorderschluder

Castle, sober but precise. The second bore the title:

Singular and Curious Description of the High-Count

Moreno’s Castle at Vorderschluder, Particularly of

All Hidden Passages, Stairs, Rooms, Secret Doors,

and Other Noteworthy Features, Compiled and

Brought to Light on the Occasion of His High-Count

Grace Louis Juan de Mereus’s Fiftieth Birthday by

Adam Zeltelhuber, Count’s Tutor, 1681.

A seventeenth-century tutor’s work. Schiereisen

owed Zeltelhuber gratitude. Honor his memory! He

couldn’t resist a quick peek. The text included neat

plans and cross-sections, marked with letters and

measurements, foolproof. A priceless find.

Hearing steps, Schiereisen slipped the booklet into

his breast pocket. Ruprecht found the Celt scholar

amid thick folios, wreathed in century-old scholarly

dust.

Leave a comment