Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers and translated by Joe E Bandel

“There Brambach, for the road! But next time be a little smarter

and do what I said. Now go into the kitchen and have some butter-

bread and a glass of beer!”

The invalid thanked him, happy enough that things had gone so

well and he hobbled back across the court toward the kitchen. His

Excellency snatched up the sweet tear vial, pulled a silk handkerchief

out of his pocket and carefully cleaned it, viewing the fine violet glass

from all sides. Then he opened the door and stepped back into the

library where the curator from Nuremburg stood before a glass case.

He walked up brandishing the vial in his upraised arm.

“Look at this, dear doctor,” he began. “I have here a most

unusual treasure! It belongs to the grave of Tullia, the sister of general

Aulus. It is from the site at Schware-Rheindorf. I’ve already shown

you several artifacts from there!”

He handed him the vial and continued.

“Can you tell me its point of origin?”

The scholar took the glass, stepped to the window and adjusted

his glasses. He asked for a loupe and a silk cloth. He wiped it and held

the glass against the light turning it this way and that. Somewhat

hesitatingly and not entirely certain he finally said, “Hmm, it appears

to be of Syrian make, probably from the glass factory at Palmyra.”

“Bravo!” cried the Privy Councilor. I must certainly watch

myself around you. You are an expert!”

If the curator would have said it was from Agrigent or Munda he

would have responded with equal enthusiasm.

“Now doctor, what time period is it from?”

The curator raised the vial one more time. “Second century,” he

said. “First half.”

This time his voice rang with confidence.

“I give you my compliments,” confirmed the Privy Councilor. “I

didn’t believe anyone could make such a quick and accurate

determination!”

“Except yourself naturally, your Excellency,” replied the scholar

flatteringly.

But the professor replied modestly, “You over estimate my

knowledge considerably Herr Doctor. I have spent no less than eight

days of hard work trying to make a determination with complete

certainty. I have gone through a lot of books.

But I have no regrets. It is a rare and beautiful piece–has cost me

enough too. The fellow that found it made a small fortune with it.”

“I would really like to have it for my museum,” declared the

director. “What do you want for it?”

“For Nuremburg, only five thousand Marks,” answered the

professor. “You know that I offer all German museums specially

reduced prices. Next week two gentlemen are coming here from

London. I will offer them eight thousand and will certainly get it!”

“But your Excellency,” responded the scholar. “Five thousand

Marks! You know very well that I can’t pay such a price! That is

beyond my authorization.”

The Privy Councilor said, “I’m really very sorry, but I can’t give

the vial away for any less.”

The Herr from Nuremburg weighed the little glass in his hand.

“It is a charming tear vial and I am inordinately fond of it. I will give

you three thousand, your Excellency.”

The Privy Councilor said, “No, nothing less than five thousand!

But I tell you what Herr Director. Since that tear vial pleases you so

much, permit me to give it to you as a personal gift. Keep it as a

memento of your accurate determination.”

“I thank you, your Excellency. I thank you!” cried the curator.

He stood up and shook the Councilor’s hand very hard. “But I am not

permitted to accept any gifts in my position. Forgive me then if I must

refuse. Anyway, I have decided to pay your price. We must keep this

piece in the Fatherland and not permit it to go to England.”

He went to the writing desk and wrote out his check. But before

he left the Privy Councilor talked him into buying the other less

interesting pieces–from the grave of Tullia, the sister of general

Aulus.

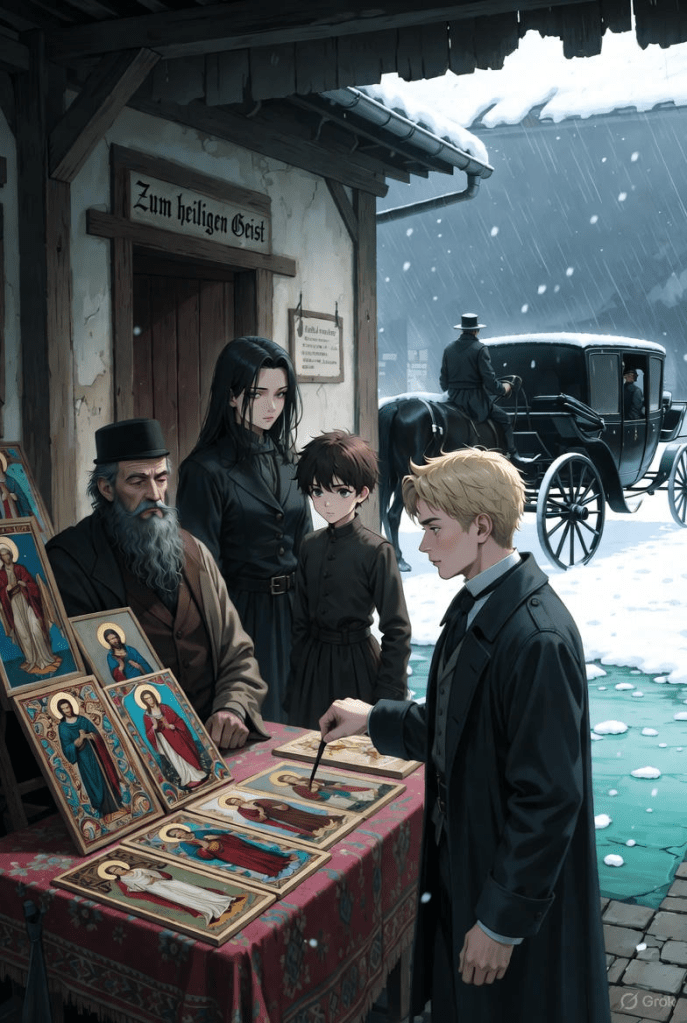

The professor ordered the horses ready for his guest and escorted

him out to his carriage. As he came back across the court he saw

Wölfchen and Alraune standing by the peddler who was showing

them his colored images of the Saints. After a meal and some drink

old Brambach had recovered some of his courage, had even sold the

cook a rosary that he claimed had been blessed by the Bishop. That

was why it cost thirty pennies more than the others did. That had all

loosened his tongue, which just an hour before had been so timid. He

steeled his heart and limped up to the Privy Councilor.

“Herr Professor,” he pleaded. “Buy the children a pretty picture

of St. Joseph!”

His Excellency was in a good mood so he replied, “St. Joseph?

No, but do you have one of St. John of Nepomuk?”

No, Brambach didn’t have one of him. He had one of St.

Anthony though, St. John, St. Thomas and St. Jakob. But

unfortunately none of Nepomuk and once again he had to be

upbraided for not knowing his business. In Lendenich you could only

sell St. John of Nepomuk, none of the other saints.

The peddler took it hard but made one last attempt. “A raffle

ticket, Herr Professor! Take a raffle ticket for the restoration of St.

Lawrence’s church in Dülmen. It only costs one Mark and every

buyer receives an indulgence of one hundred days. It says so right

here!”

He held the ticket under the Privy Councilor’s nose.

“No,” said the professor. “We don’t need any indulgences. We

are protestant, that’s how we get to heaven and a person can’t win

anything in a raffle anyway.”

“What?” the peddler replied. “You can’t win? There are over

three hundred prizes and the first prize is fifty thousand Marks in

cash! It says so right here!”

He pointed with a dirty finger to the raffle ticket. The professor

took the ticket out of his hand and examined it.

“You old ass!” he laughed. “And here it says there are five

hundred thousand tickets! Calculate for yourself how many chances

you have of winning that!”

He turned to go but the invalid limped after him holding onto his

coat.

“Try it anyway professor,” he begged. “We need to live too!”

“No,” cried the Privy Councilor.

Still the peddler wouldn’t give up. “I have a feeling that you are

going to win!”

“You always have that feeling!” said the Privy Councilor.

“Let the little one choose a ticket, she brings luck!” insisted

Brambach.

That stopped the professor. “I will do it,” he murmured.

“Come over here Alraune!” he cried. “Choose a ticket.”

The child skipped up. The invalid carefully made a fan out of his

tickets and held them in front of her.

“Close your eyes,” he commanded. “Now, pick one.”

Alraune drew a ticket and gave it to the Privy Councilor. He

considered for a moment and then waved the boy over.

“You choose one too, Wölfchen,” he said.

In the leather volume his Excellency ten Brinken reports that he

won fifty thousand Marks in the Dülmen church raffle. Unfortunately

he could not be certain whether Alraune or Wölfchen had selected the

winning ticket. He had put them both together in his desk without

writing the names of the children on them. Still he scarcely had any

doubt that it must have been Alraune’s.

As for the rest, he mentions how grateful he was to old

Brambach who almost forced him to bring this money into the house.

He gave him five Marks and set things up with the local relief fund

for aged and disabled veterans so that he would receive a regular

pension of thirty Marks per year.

Leave a comment