Madame Bluebeard by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

They discussed the year’s events. Hugo extracted

Helmina’s promise to attend every festivity.

The afternoon passed. They took a short drive.

The weather had cleared, the thinning clouds hinting

at the sun. Hugo wished to prolong the day, but

evening approached, they returned to the castle,

dined, and his departure loomed.

“I feel so at ease here, madam,” Hugo sighed.

“You may return if you enjoyed it,” Helmina

smiled. Then she excused herself. The fresh air had

tired her, she had a headache, and wished to retire.

The men adjourned to Ruprecht’s study. “A cigar,

a glass of wine, eh?” Ruprecht suggested, ringing the

bell. The Malay appeared at the door.

“Tell Lorenz to fetch a bottle of 1882

Schönberger,” Ruprecht said.

“Lorenz isn’t here.”

“Oh, right—he’s on leave. Linz, or somewhere.

Get the keys and fetch it yourself. You’ll find it. It’s

at the back of the cellar, red-sealed.”

Meanwhile, Hugo surveyed the study’s

furnishings. At the café’s regular table, they had an

arts-and-crafts enthusiast skilled in style

comparisons, giving Hugo a rough sense of Gothic,

Renaissance, and Rococo to prove his cultured

credentials. Here were charming relics: a heavy

cabinet with carved columns and armored men on its

doors; a desk with dainty, curved legs and an oddly

uncomfortable top, fit only for brief love notes, not

serious work. For that, Ruprecht used a cozy

Biedermeier desk, its genial polish beside a sleek

black filing cabinet with lapis lazuli and marble-lined

drawers, supported by two gilded, snarling griffins.

“Ancestral heirlooms,” Hugo said. “The castle’s

full of them.”

“Yes… some are exquisite. Next visit, I’ll show

you a Wenzel Jamnitzer goblet. Dankwardt even

started a medal and seal collection. I know too little

about it.”

“These pieces likely came with the castle from

earlier owners?”

“Not many. The Counts of Moreno, from whom

Helmina’s first husband bought it, stripped it bare.

Later owners were collectors, gradually bringing

things back.”

“Fine pieces… truly! They hold their own. The

whole castle…”

“Yes, the castle’s worth seeing.”

“You’re a lucky man… and your wife…” Hugo

stretched in his seventeenth-century armchair. “You

have a delightful wife.”

Ruprecht glanced at him briefly, saying lightly,

“You haven’t fallen for her, have you?”

A reassuring laugh should’ve followed, but it

sounded forced. “It’d be no wonder,” Hugo said, then

continued, “Tell me, aren’t you ever jealous of your

wife’s past? You’re her fourth husband.”

“It’s not my way. I find that kind of jealousy

absurd.”

“But in this castle… everything must remind you

of your predecessors.”

“It wasn’t entirely pleasant at first. Life’s a

ceaseless flow, washing away past impressions

quickly. The past clings more to dead things. These

furnishings and rooms reflect my predecessors far

clearer. In Helmina, they’re dissolved, swept away by

life.”

“Haven’t you thought of building a new home?

One where… only you exist?”

“Helmina’s attached to these walls… oddly so.

She craves city lights, glamour, noise—she had a

wild Carnival. But this castle holds her. She always

returns. She’d never agree to live elsewhere. And… I

find this grim house intriguing. It has charm… it’s,

how to say… an adventure, a romantic danger…”

Ruprecht’s nonchalance emboldened Hugo,

tempting him to play with fire. “And the present… I

mean, Helmina’s present?”

“I don’t follow.”

“Aren’t you jealous of that?”

“Oh, I’m pleased when people pay Helmina

tribute. Besides, I’m certain of her.”

He’s insufferable, Hugo thought, fuming, and it’s

maddening that he’s right.

Jana returned with bottles, fetched glasses from

the armored-men cabinet, and poured. Ruprecht took

a cigar box from a filing cabinet drawer. Hugo

glimpsed a revolver inside.

“You’re armed,” he said. “Even here?”

“Old habit,” Ruprecht smiled. “In Alaska, I

worked months with a rifle beside me…”

As Ruprecht raised his glass to toast Hugo, he

noticed dirty smudges, like wet earth, on Jana’s white

turban.

“Bumped your head, Jana?” he asked.

“I fell, Master,” the Malay replied. “Water’s

seeped into the cellar, washing it out a bit…”

“Hope the bottles don’t float away.”

Hugo hadn’t heard, spreading the subscription

sheet before Ruprecht, who signed.

“Enough?” the castle lord asked.

“Oh, you’re an angel. Thank you. Truly, I name

you chief patron, top of all sponsors… I’ll honor you

somehow, just need to think how.” Hugo launched

into his anthology, its hopes, its prospects for

recognition from high places. His wine-fueled

imagination bloomed like a Jericho rose. This

anthology would be an event. All notable authors

would contribute. Bystritzky had connections, even

inviting Gegely, though that awkward incident…

“Ah, Gegely,” Ruprecht said, suddenly animated

after listening politely. “I’ve heard nothing of him

lately. I don’t read papers—waste of time. What’s

our famous poet up to?”

Hugo slapped the chair’s smooth arms. “You

really don’t know? Nothing about Gegely… my God,

it was a European scandal…”

“I swear, I know nothing…”

“Well, Gegely… it’s unthinkable… psychologists

are baffled. Our great Gegely, our hope, our pride,

poet of Marie Antoinette… what do you think? He…

he took a manuscript from Heidelberg’s university

library… let’s say, accidentally.”

Oh, the thrill of breaking such news first, asserting

one’s importance. It was a hearty delight, a bold

affirmation of self.

How it shook his friend. Ruprecht paled, his brow

damp. “Is it possible…” he stammered, “he stole…?”

“Well—stole? Legally: yes. Psychologically: a

momentary lapse.”

What bliss to cause such a stir. Gegely, another

carefree glutton for wealth, ignorant of the grind of

being rank-bound, salary-tied.

“How could it happen?” Ruprecht asked, still

reeling.

“No idea what possessed him. He could’ve bought

such scraps by the dozen at an antiquarian’s. It

kicked up a storm… a European scandal, as I said.

They tried to save him, of course… spun theories

about the phenomenon… and finally draped a nice

veil over it…”

“What happened to him?”

“He was put in a sanatorium… a ‘U’ became an

‘X,’ as such cases go. You’ll see… Bystritzky invited

him to contribute to the anthology before this

happened. It’s awkward now. If he sends something,

can we accept it?”

“Poor woman,” Ruprecht said thoughtfully,

swirling his wine.

“Frau Hedwig… yes, terrible for her!” A sudden,

delicious thrill hit Hugo. A memory surged. “Frau

Hedwig, the blonde… say, didn’t you once…?” He

squinted gleefully. “It hurt you deeply, didn’t it,

when Gegely took her from you? You were smitten.

Still think of her?”

“Oh, come now!” Ruprecht said softly, stiffening

in resistance. “A youthful acquaintance. It was long

ago… I pity her… having to endure that.” He stood,

pulling out his watch. “If you want to catch your

train, it’s high time to leave.”

Hugo regretted leaving his scene of triumph. He’d

have savored it longer. Ruprecht escorted him to the

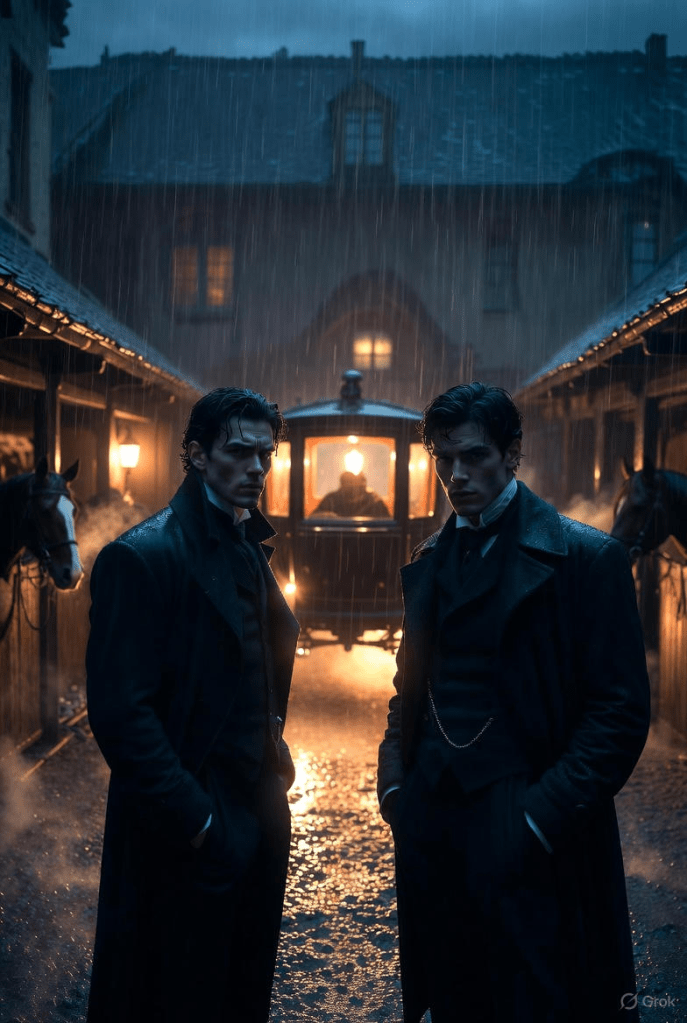

courtyard. They lingered, shivering, in the renewed

rain. The carriage emerged from the stable, its dim

lights casting trembling patches at their feet. The

horses snorted, restless, loath to leave the warm

stable. The courtyard felt like a pit’s bottom,

darkness rising in steep walls around them.

“Well, thanks for everything,” Hugo said,

climbing in. “Hand-kiss to your wife. So… our

anthology? What do you think…” He poked his

pinky through his overcoat’s buttonhole. “How’d this

suit me?”

“Splendidly!” Ruprecht replied evenly. “You were

born for a medal…”

“Here’s hoping!” Hugo laughed, closing the

carriage door. The carriage arced around Ruprecht

and out the gate.

Leave a comment