Homo Sapiens: Under Way by Stanislaw Przybyszewski and translated by Joe E Bandel

“Doesn’t she have a lampshade? He couldn’t stand the brutal light.”

Marit brought the shade.

The conversation kept stalling.

“You mustn’t mind, Marit, if I stay longer with you today. I can’t sleep anyway; and then, you know, when I am so alone… hm… I don’t disturb you?”

Marit’s face colored with hectic red. She couldn’t speak; she only nodded to him.

They sat silently for a while. The whole village slept. The big house was as if extinct. The servants had already gone to rest. The sultriness was almost unbearable. A stuffy calm weighed on both, the dull air outside pressed into the room, and the regular ticking of the clock caused almost physical pain.

“It’s strange how lonely one is here; it’s uncanny. Don’t you sometimes have fear when you are so completely alone in this big house?”

“Oh yes, I feel it terribly strongly. Sometimes I feel so lonely and abandoned here, as if I were completely alone in the world. Then I get such a horrible fear that I want to bury myself in the earth.”

“But today you don’t feel abandoned?” “No!”

Again a pause occurred; a long, heavy-breathing pause.

“Listen, Marit, do you still have the poems I wrote for you last spring? I would so like to read them again.”

“Yes, I have them in my room; I will fetch them immediately.”

“No, Marit; I will go up with you. It is much cozier in your room; so wonderfully cozy. Here it is so uncanny, and I, you see, am very, very nervous.”

“Yes, but someone could hear that you go with me; that would be terrible for me.”

“Oh, he would go quite quietly, quite softly; no person should hear him. Besides, the whole house is asleep.”

She still resisted.

“Sweet little dove, you really need have no fear. I will do nothing to you—nothing, nothing at all. I will sit quietly beside you and read the poems.”

It thundered.

“Yes, quite quietly; and when the storm is over, I will go home calmly…”

They entered Marit’s room; they felt as if rooted to the spot. There was an atmosphere between them that seemed to live.

Suddenly Marit felt herself embraced by him. Before her eyes fiery bubbles swirled, again she saw the hot jubilation dancing over the abyss, she wove her arms around him and plunged headlong into the gruesome happiness.

Suddenly she started up.

“No, Erik! only not that… Erik, no! No!” She gasped.

Falk let her go.

He mastered himself with difficulty. A long pause.

“Listen, Marit—” his voice sounded rough and hard—”now we must part. You see, you are cowardly. You are a little dove, a rabbit; and I am a good man. I am the good, dear Erik. Well, Marit, you don’t have the courage to say to me: Go, leave me my pure conscience, leave me the idiotic virginity. You don’t have this courage. Well, I am a man; and so I go; let come what will.”

“Yes, I go. I leave you your morality, I leave you your religious conscience, I leave you your virginity, and spare you the so-called sin. Now be happy; very, very happy…”

The storm grew louder; in the window green furrows of lightning were seen.

Falk turned to the door.

“Erik, Erik, how can you be so cruel, so bestially cruel?!”

The whole laboriously suppressed misery of her soul broke forth. She writhed in pain.

“Erik! Erik!” she whimpered.

Falk got a mad fear.

He ran to her, took the twitching girl’s body in his arms.

“No, Marit, no; it’s madness. I stay with you. I will never leave you. I can’t go away from you. You see, I thought I could. But I can’t. I must be with you; I must. I will never leave you. No, Marit; you my only happiness.”

The thunder rolled ever closer.

“I stay always with you. Always. Eternally. You are my wife, my bride, everything, everything.”

A wild passion began to whirl in his head.

And he rocked her in his arms back and forth and spoke incessantly of the great happiness, and forgot everything.

“Yes, I will make you happy… so happy… so happy…” A cloudburst wave splashed against the windowpanes.

Now they were really alone in the world. The rain, the lightning fenced them in.

Marit embraced him.

“Erik, how good, how good you are! Yes: not away! We stay always together. We will be so happy.”

“We stay always together!” repeated Falk, as if absent. Suddenly he came to his senses. Again he felt the hard, cruel

in himself, the stone that falls into abysses. He pressed her tighter and tighter.

They heard not the thundering, saw not the fire of heaven. Everything spun, everything melted into a great, dancing fireball.

Falk took her…

The storm seemed to want to move away. It was three in the morning.

“Now you must go!” “Yes.”

“But not on the country road. You must go along the lake and then climb over the monastery fence. Otherwise someone could see you, and tomorrow the whole town would talk about it.”

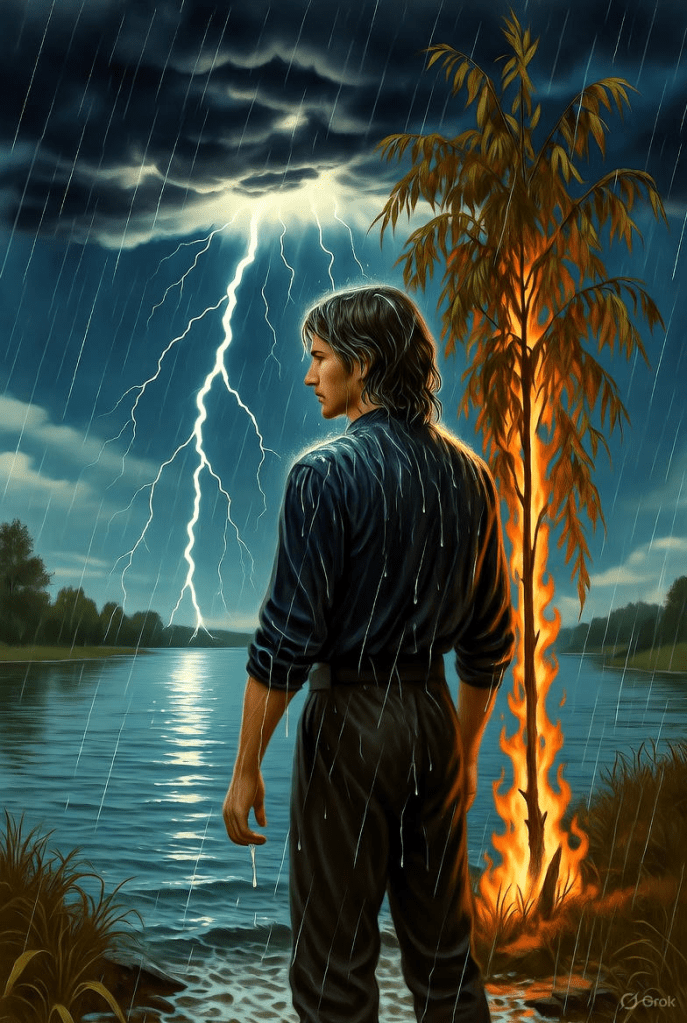

When Falk came to the lake, a new storm drew up.

He should actually take shelter somewhere. But he had no energy for it. Besides, it was indifferent whether he got a little wet.

The sky covered itself with thick clouds; the clouds balled together visibly into black, hanging masses.

A long, crashing thunder followed a lightning that tore the whole sky apart like a glowing trench.

Again a lightning and thunder, and then a downpour like a cloudburst.

In a moment Falk felt streams of water shooting over his body. But it was no particularly unpleasant feeling.

Suddenly he saw an enormous fire-garland spray from the cloud heap; he saw it split into seven lightnings and in the same moment a willow stand in flames from top to bottom. It was torn from top to bottom and fell apart.

“Life and destruction!”

The shock had roused his logic; he also had to calm the fear-feeling that wanted to rise in him again.

“Yes, of course, hm: destruction must be. Marit… Yes… destroyed…”

Falk suddenly had this clear, lightning-bright, visionary consciousness that he had destroyed Marit.

“Why not? I am nature and destroy and give life. I stride over a thousand corpses: because I must! And I beget life upon life: because I must!

I am not I. I am You—God, world, nature—or what you are, you eternal idiocy, eternal mockery.

I am no human. I am the overman: conscienceless, cruel, splendid and kind. I am nature: I have no conscience, she has none… I have no mercy, she has none…”

“Yes: the overman am I.” Falk screamed the words.

And he saw himself as the deadly fire-garland that had sprayed from the black vault: into seven lightnings he had split and torn a little dove by the wayside. Into a thousand lightnings he must still split and tear a thousand little doves, a thousand rabbits, and thus he would go eternally and beget and kill.

Because it is necessary. Because I must.

Because my instincts want it.

Because I am a non-I, an overman. Does one need to torment oneself for that? Ridiculous!

Does the lightning know why it kills? And has it reason, can it direct its lust?

No! Only constate that it struck there and there. Yes: constate, protocol—like you want, Herr X.

And I constate and protocol that today I killed a little dove…

The atmosphere was so overloaded with electricity that around him a sea of fire seemed to sway.

And he walked, enveloped in the wild storm; he walked and brooded.

And in the middle of this wrath of heaven he himself walked as a wrathful, uncanny power, a Satan sent to earth with a hell of torments to sow new creative destruction over it.

Suddenly he stopped before the ravine.

It was completely filled with water. A torrent seemed to have sprung up and streamed rushing to the lake.

He couldn’t go around it; there he would come to the cursed country road.

Besides, it’s indifferent: a bit more water, a bit more chills and fever: no, that does nothing.

That does nothing at all. Everything is indifferent; quite, quite indifferent.

And he waded through the torrent.

The water reached above his knees.

When Falk came home and lay down in bed, he fell into a violent delirium; all night he lay and tossed back and forth in the wildest fever phantasies.

Leave a comment