Madame Bluebeard by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

The beach grew livelier, so after a brief

continuation of the conversation, which turned to

other topics, Ruprecht invited his friend for a walk.

They strolled along the shore, then climbed toward

the heights between villas and hotels. Sky and sea

shimmered in boundless clarity. The setting sun

seemed to conjure all the sea’s gold from its blue

depths. A refreshing coolness rose from below,

mingled with the scents of myriad blossoms and

fruits, woven into a dense garland around the coast.

The summer was wondrously beautiful, blessed with

constant sunshine yet tempered by a lively, cooling

breeze that prevented scorching heat. No one wanted

to leave this shore. The season stretched far beyond

its usual end, into a time when all would typically

have fled.

Ruprecht and Hugo reached a rocky outcrop

offering a clear view of the coast and sea. Before the

low sun hung a narrow cloud, like a knife poised over

an orange. The sea was calm, bearing fishing boats

with a willing smile.

“There’s the scene of your heroics,” Hugo said,

pointing to the two white stone cubes among the

vineyards where Ruprecht had lassoed Mr. Müller.

“What made you get involved? It was decidedly

original, but… one doesn’t just help the police like

that, do they?”

“You can imagine I found Mr. Müller more

likable than the helpless police commissioner. Still—

why? The bit of danger intrigued me. I think danger’s

one of the sweetest pleasures life offers.”

“You find too little of it in our quiet Europe.

That’s why you roam the world, seeking wilder

places. God, you’ve got it good! No one to answer to,

money like hay, doing as you please. I’d love to

travel too—not like you, but with pleasant company,

under Cook’s care, so I don’t wake up in a Papuan’s

stomach.”

Ruprecht smiled, gazing silently at the sea. Then,

with a sweeping half-circle of his arm, he

encompassed the beauty spread before them. “Only

those who know struggle,” he said, “can truly

appreciate peace. How glorious this is. How the soul

simplifies, how wings grow.”

A faint chime rose over sea and land. Like a

delicate, firm web, the peals of church bells, ringing

the evening blessing, stretched through the clear air.

The friends sat silently for a while. Then Hugo

reminded them to head back to avoid missing dinner

at the hotel. They descended quickly through the

twilight, past orchards and vineyards, and at the

Kaiser von Österreich, Hugo parted with a promise to

visit again tomorrow.

Reaching his room, Ruprecht began changing. He

was in high spirits. The evening’s colors and sounds

had sunk into him, filling him with joy. He always

felt this way on the eve of new adventures, brimming

with expectation and eager energies. Yet he knew

only months of quiet country life awaited,

somewhere with few people and no events.

As he donned his dinner jacket, his Malay servant

entered the dressing room, standing erect by the door.

“What is it?” Ruprecht asked.

“Sir, a woman wishes to speak with you. She’s

waiting in the salon.”

Somewhat surprised, Ruprecht followed. Before

entering, he placed a hand on the Malay’s shoulder.

“Wait! Is she one of those you visited on my behalf?”

“Yes, sir.”

Well, by all the gods of Hindustan, she was

persistent! That was something! A strange way to

approach a stranger. Smiling, Ruprecht entered the

salon.

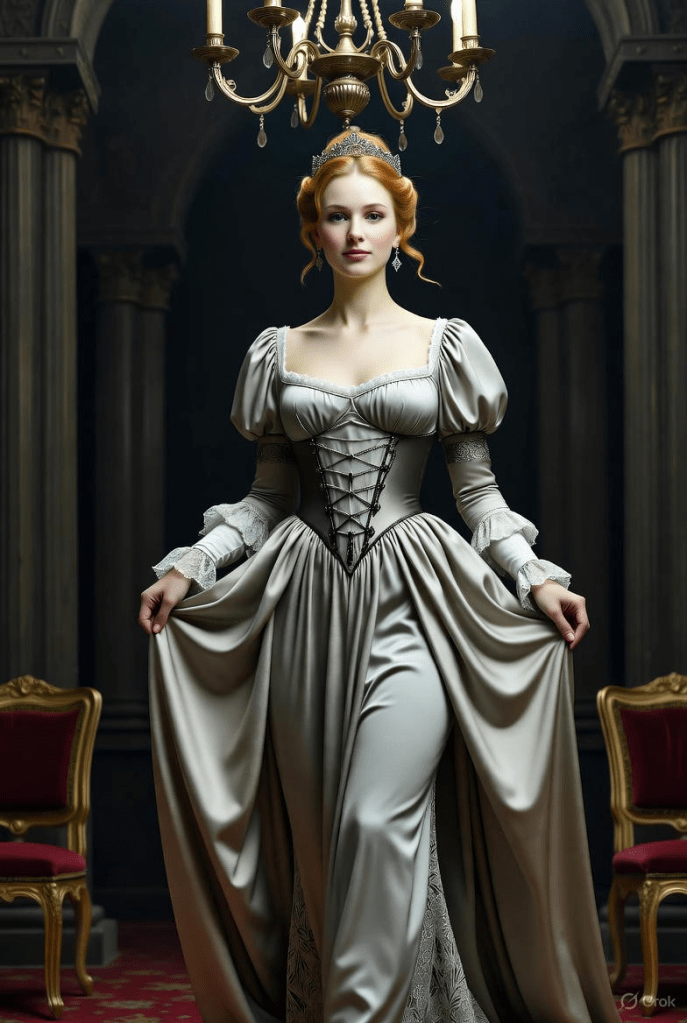

Under the chandelier stood the young widow who

enchanted all, the woman who sat front-row at the

Emperor’s celebration. She smiled too. Ruprecht

bowed.

She took a few steps toward him. Silk skirts

rustled, a faint cloud of perfume wafted over. A

peculiar scent—dried fruit, hay, and something else

Ruprecht couldn’t pinpoint.

“You thought, on your way here, that I’m

persistent,” she said. “You found it odd to answer a

refused meeting with a visit.”

“You’re very perceptive, madam!” Ruprecht

replied.

“Oh, come, that hardly takes perception—it was

clear in your smile. Well, see, I’m smiling too. And

do you know what my smile says? It expresses my

pleasure in proving you wrong.”

Ruprecht met her eyes—green, with narrow

pupils, seeming to drink in light and scatter it in a

thousand rays, as if dissecting it. Cat’s eyes, he

thought. They held that indefinable expression,

neither clearly friendly nor hostile.

“I’m no starry-eyed schoolgirl,” she continued,

“nor an adventure-seeking woman. I’m not after a

flirt or a fleeting resort acquaintance. I simply want

to meet you, exchange a few words, to know what to

make of you.”

The perfume, seeping from her exquisite lace

gown and soft brown hair, unsettled Ruprecht. He,

who’d studied the Orient’s delicate, provocative

scents, was uneasy at failing to identify this elusive

note.

“Forgive me,” he said slowly, “your letter was one

among many. It didn’t stand out.”

She laughed. “Then your perception failed you.

You should’ve seen at once I’ve no intention of

throwing myself at you with loving gestures.”

What does she want, then? Ruprecht thought. Her

gaze, accompanying those words, didn’t align with

them. It didn’t contradict, but clung to him—a

promise given and withdrawn, a granting that was

also a retreat.

“I could do so more easily than others,” she said,

“for I answer to no one. You’d only have to fight two

or three duels with my ardent admirers. That

wouldn’t trouble you, would it? But truly, I only wish

to know if you’re as vain as they say.”

Ruprecht flinched. The word stung. He

straightened slightly and said, “Madam…”

She smiled again. “Hold on… I find it improper to

parade in costume as a wild man before a respectable

audience, shooting holes in cards and shattering glass

balls. Isn’t that a far worse surrender of one’s person

than other artistic pursuits, which are already

deplorable prostitutions? My late husband studied

Indian philosophers. He called the arts silver

embroidery on Maya’s veil—something special,

glittering, yet part of the web of illusions. You know

Schopenhauer thought differently. But I believe my

husband was right.”

Ruprecht stood dumbfounded. What did this

woman want, with her odd jumble of “personality,”

“Maya’s veil,” and Schopenhauer? Was this an

original worldview or mere confusion? He grasped

only that she presumed to judge him, acting as if she

had a right to challenge him, which irked him all the

more since he hadn’t fully shaken the shame of his

performance.

“Forgive me,” he said, mustering a blunt defense,

“I believe I’ve proven vanity has no hold over me.”

“Oh, certainly,” she laughed, “you didn’t attend

the rendezvous. But… isn’t that a ploy? Perhaps

you’re spoiled. Who knows? In my presence, a bet

was made that you’re not vain. I judged from your

sharpshooting display and took the wager. Now, I

must admit—you didn’t come, and it seems I’ve lost.

Yet I’d like to know if I haven’t won precisely

because of that. I suspect you aim to stand out in a

unique way.”

“I’ve no such intention,” Ruprecht said, annoyed.

“It was a favor for my friend. I was persuaded. And

before… the lasso affair was just for the thrill of

it…”

At that moment, the dinner gong clanged in the

hall below—a long, wild peal, a hideous noise

piercing every corner of the hotel, even through the

salon’s heavy curtains, drowning all other sounds.

Three single strikes followed.

“You’re summoned to dine,” the widow said. “I’ll

go. Well… I must accept my bet is lost. What else

can I do? Thank you for listening so kindly.”

She offered her slender hand freely, meeting his

eyes with equal ease.

“Let the gong make its racket,” Ruprecht said,

agitated. “You come here, insult me with your

suspicions… yes, forgive me, I find that offensive.

Let me explain… I was deeply vexed at getting

involved. No… please, I don’t care about being late

for dinner.”

But the young widow insisted she couldn’t bear

the guilt, nor did she wish to draw attention at her

hotel by arriving late to table. Yet her eyes said

something else: Oh, foolish man, happiness stands

before you, just reach out.

Leave a comment