OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

Are those tears in Semmelweis’s eyes? Reichenbach thought madmen couldn’t cry, and in what Semmelweis just said, there’s nothing incoherent.

Suddenly, Semmelweis wheels around, fear and rage twisting his pained face back into a grimace. “They’re coming!” he shrieks. He leaps over the bench, falls, scrambles up, and hurls himself into the bushes. He races down the hill; for a while, you hear the crack and snap of branches, then he’s gone like a wild, hunted dream figure.

If Severin weren’t standing there, bent forward, leaning on his stick with narrowed eyes, Reichenbach might believe it was all just a dream. But Severin, who witnessed it, testifies to its reality. Rubble and ruins everywhere you look, and old men stand there, unable to clear the debris and start anew, as would be needed.

Then Reichenbach recalls something is required of him. Even when you want to let your hands drop and extinguish your will, life demands something. “Severin,” he says, “Rosina has fallen ill. Would you care for me and nurse Rosina for now?”

Severin nods. Yes, he’ll care for the Freiherr and nurse Rosina. He’ll do it. And perhaps that’s what Severin has been waiting for all along, sitting on his bench before the castle.

The doctor has been and given his instructions.

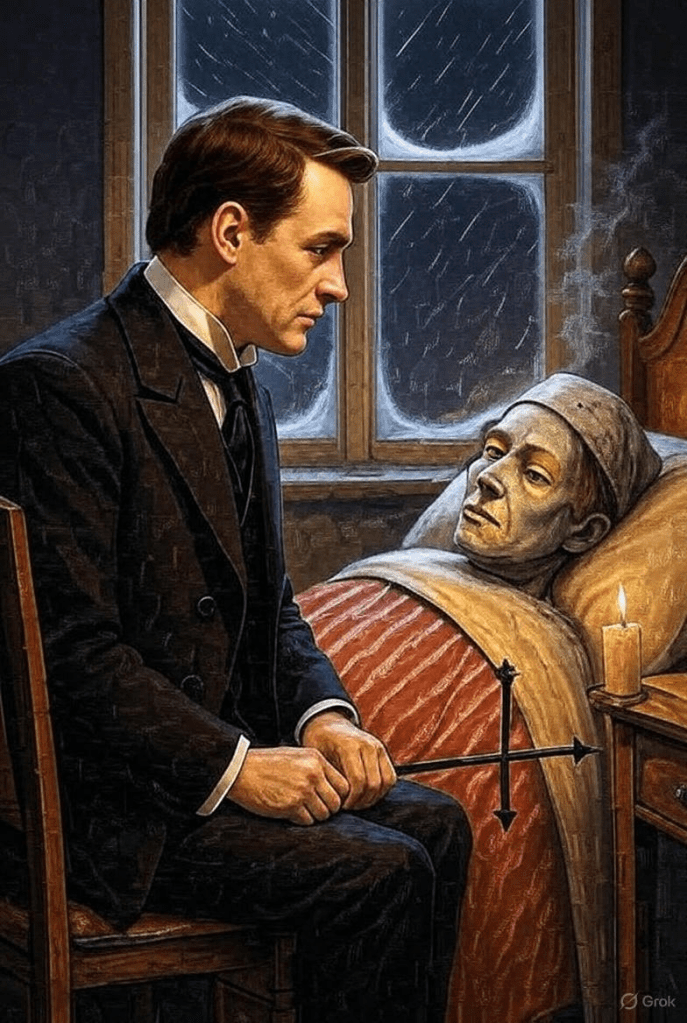

Severin escorts him out and returns to the sickbed.

“Yes, that’s a nasty illness,” he says, pulling a chair to the bed and sitting at a measured distance—not too close, God forbid! He acts as if the doctor confided in him specially and filled him in.

Frau Rosina lies in bed, the red-and-white striped blanket pulled to her chin, only her grayish-yellow face visible under a grimy nightcap.

“A nasty illness,” Severin repeats with relish, “very nasty. Could drag on for months. I wouldn’t want to be sick that long. When my time comes, I’ll lie down and die quick.”

“I won’t stay in bed for months,” Rosina vows grimly. She’s not supposed to move much, but she’s boiling with rage, the nightcap’s edges trembling.

“Oh, you could get up right now,” Severin says with deep satisfaction, “but then it’s over for you. My respects, obedient servant! With an illness like that, you collapse and die sudden-like. You can count on it, that’s how it is.”

“Now I’ve had enough,” Rosina snaps across, “shut your mouth for once.”

Oh, Severin has no intention of staying quiet. He finally has the floor and won’t let himself be stopped from making full use of it. Frau Rosina Knall is rendered harmless, lying in bed with her legs propped up, wrapped in thick compresses, unable to move and forced to listen to what’s said. Severin sits at a safe distance, pulls out his pipe, carefully packs it, lights it, and blows three leisurely blue smoke clouds. The old Severin is no longer a salty, shaky old man; he’s lively and sharp, puffing away like a freshly stoked locomotive.

The sound of puffing and the smell jerk Frau Rosina, who had turned her face to the wall, around: “Stop it,” she rants, “away with that pipe. You’ll stink up the whole room. The Herr Baron can’t stand pipes—he can’t stand smoking at all.”

Three new giant clouds billow into the room; thin, blue wisps of pungent smoke drift over Rosina’s bed and sink into the corners. Severin maintains his calm cheer: “I know,” he says, “when the Herr Baron comes, I’ll put the pipe away.”

“I can’t stand it either,” Rosina hisses.

Shaking his head, Severin observes the patient. Is it true you can provoke toads until they burst with bile and venom? Frau Rosina also reminds him of a simmering pot, its contents rattling the sides and lifting the lid. “Strange,” he muses, “some folks can’t stand smoking. I’m mighty fond of it. Nothing better than a pipe. Oh—what I meant to say. Things’ll change now; the Herr Baron will see people again. You can’t leave him so alone. I already mentioned that Frau Hermine came by with her husband and child recently. And we’ll need a chambermaid and a cook. I’m not one of the youngest anymore, and when you’re allowed up, you’ll need to take it easy for a long while.”

Everything Rosina built crumbles to shards. It slips through her fingers. This old fool sits by her bed puffing his pipe, and Frau Rosina lies powerless, nearly choking with rage.

“Sister’s child,” Severin returns to his main theme, “had it too. Got up too soon, and the illness came back. And she was a young, spry thing—with old women, it’s always twice as bad—”

Despite his geniality, Severin keeps a sharp eye. He notices a suspicious movement: one of the patient’s arms slides out from under the blanket, her yellow hand reaching for the nightstand where the medicine bottles stand. It’s astonishing how quickly old Severin can leap from his chair and dart out of the room. The large medicine bottle shatters with a crash against the already-closed door.

He giggles gleefully, in high spirits, as he potters through the kitchen and down the hall, lighting the lamp in the entryway. The door to Freiherr von Reichenbach’s quarters now stands open again, a lamp illuminating the path; people should know the dragon guarding him has been chained. And indeed, someone is already in the entryway, someone who lingered in the dark, not daring to venture further. It’s a shabbily dressed, gaunt woman; Severin doesn’t know who she is, a tattered bonnet shadowing her face, but he’s full of goodwill and courtesy even to such a poorly clad woman. He’s set on letting life reach the Freiherr again and sees no need to discriminate.

“Here to see the Herr Baron?” he asks kindly. “Come with me.” Without waiting for a reply, he strides ahead, knocks firmly on the study door, and when the stranger hesitates at the last moment, as if having second thoughts, he gently takes her arm and ushers her in. “Herr Baron, someone wishes to speak with you.”

Reichenbach looks up from his work, surprised by the late, odd visitor Severin has brought. But then he shoves his chair back and rises.

“Is it you?”

So it has come to pass, what Friederike saw as a distant glow in anguished, sleepless nights, amid the depths of her disgrace. There is Reichenbach’s study, the lit desk strewn with papers, and the Freiherr himself, an old man with a bald head and furrowed face, tufts of yellowish-white hair at his temples.

And Friederike is back, haggard, in tattered clothes, one might say ragged, fallen low, a shadow of her former self.

“Where have you come from?” the Freiherr asks softly.

Friederike glances nervously behind her: “From hell.”

And then the miracle happens. Reichenbach opens his arms, and Friederike may rest her head on his chest. My God, is this real—not a delusion? Is this living human closeness, refuge, and salvation? Will they not drive her from this threshold?

“You’ll stay with me now?” Reichenbach asks.

He asks if Friederike will stay. Does he not know she’s come to leave it to him whether she’s cursed and cast out or blessed and redeemed, whether she must turn to the final darkness or receive life? She clings to him, sinking, and Reichenbach must support her and lead her to the sofa. He tosses a stack of books to the floor, making room for Friederike, who sits with her hands folded in her lap—thin, wasted hands nestling together like disheveled, scattered birds.

Leave a comment