OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

“Does he know yet?” whispered Ottane, gesturing toward Schuh.

“Not yet.”

Ottane pulled her sister into a warm, tender embrace. Ah yes, that was reason enough to smile—when such an oblivious man voiced longings for Italy, doomed to fail by such tiny things.

With the discovery that Reichenbach loved Friederike, a new phase of his Od research began. He forgot everything else and didn’t even feel the full weight of the blow that shattered his hopes for the railway tracks. The world sank away for him; he lived with Friederike as if on a lonely island amid an empty ocean.

Friederike moved quietly around him, tending to all his needs without fuss. Reichenbach didn’t even realize it was thanks to her that warmth returned to his life. He had his men create hidden paths through the forest, cutting straight through the underbrush where he met no one. There he wandered, hands behind his back, pondering his grand problems; he believed he noticed that thinking was sharper and clearer while marching about. When he reached the farthest point and turned back toward the castle, he felt joy. He rejoiced at returning from solitude to the warmth of human presence, though he didn’t dwell on the reasons.

Friederike submitted willingly to all the experiments he conducted with her. She was happy when Reichenbach told her he had found no other sensitive like her. In her, all the qualities he’d found separately in others were united. He told her this, and she took pride in it, unaware of the latent powers within her that Reichenbach had unlocked. Only about her somnambulistic abilities did he say nothing, lest it cloud her innocence. She falls asleep at a glance from him and awakens at his command, unaware of what transpired.

“Would you go with me to the cemetery?” Reichenbach asked one day after a long forest walk that brought him new ideas.

Friederike looked a bit surprised but nodded.

“At night? Won’t you be afraid?”

Even at night! Why should she be afraid with Reichenbach beside her? His word is Friederike’s gospel; she sees him reign over her, walking resolutely and devotedly in his grace. In the darkroom, she sees the Freiherr in the glow of Od light as a radiant, white giant, immensely magnified, head and heart in brighter light than the rest—yes, that’s his true form and appearance, elevated above other humans. All should see him as she does and bow before him.

It’s a windy early spring night with mild clouds against a deep dark sky. Reichenbach has donned a weather cloak and given Friederike a man’s coat as well. They walk side by side down through the forest toward the Sievering cemetery.

Reichenbach had instructed the gravedigger to leave the cemetery gate open. The iron grille clangs back, and now the man and the girl walk among the molehills of death. The wind howls, the trees rustle in the darkness—everything is present to make a nighttime cemetery eerie. But how could anything be eerie for Friederike with Reichenbach at her side? External things can’t reach her directly; they must pass through Reichenbach and are transformed by him.

“You mustn’t think,” says the Freiherr, “that I intend to conjure spirits.”

No, Friederike doesn’t believe that, since Reichenbach says so.

“It’s like this…” he continues, “that all living things are permeated by Od and odically influence everything else in a specific way. All living things are od-negatively charged, and a sensitive can distinguish them from the dead by sensation alone, even if the living seems dead. I know a case… there was a young girl who fell into illness from great heartache and died. She was about to be buried, but the doctor wouldn’t allow it. After three weeks, she awoke from her apparent death and later married that same doctor out of gratitude. I believe that man must have been unconsciously a sensitive. And my friend, the Old Count Salm, told me that a seemingly dead countess was interred in the Salm crypt. But it didn’t go well for her; she had to perish.”

“Terrible,” says Friederike, now gripped by a shudder.

“And the painter Anschütz told me that while studying anatomy, he once, with the prosector, cut open a man’s abdomen. They stepped out for a moment to light a cigar, and when they returned, the man was sitting on the dissection table, looking at his opened belly. He too was only apparently dead and revived by the cut. It’s a dreadful matter, this apparent death, because doctors have no means to distinguish the apparently dead from the truly dead. But a sensitive knows instantly whether a person is dead or still alive, and thus Od could become a remarkable blessing for humanity. But of course, those blockheads wouldn’t admit it.”

Friederike presses anxiously closer to the Freiherr. She truly doesn’t know why he brought her to the cemetery—should she perhaps detect the apparently dead here?

“No,” says the Freiherr, having guessed Friederike’s thoughts, “those here are likely all truly dead. But even chemical processes are accompanied by Od light. You’ve seen the rotting herring glowing down in the cellar, haven’t you? Fermentation, decay, putrefaction—there’s always something odic involved. A person is dead, but as long as they haven’t fully decomposed, they must still emit an odic light. And now I want to know if you can see any of it.”

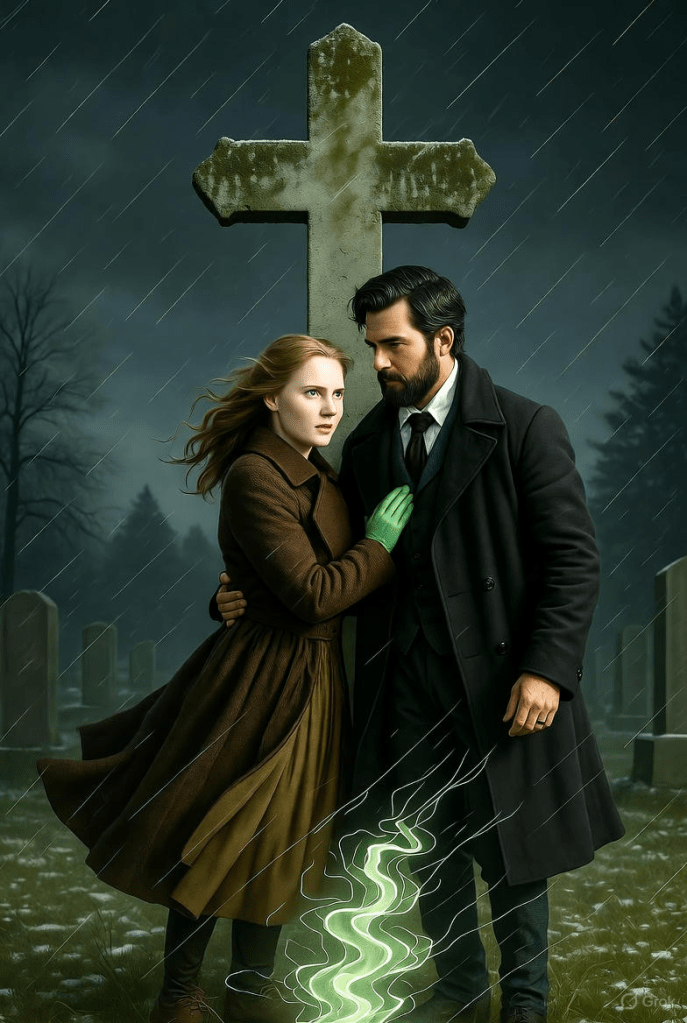

They stand by the stone cross in the center of the cemetery, surrounded by graves in the darkness of the stormy night. Friederike can’t help but cling to Reichenbach, and he places his arm around her shoulders.

She strains to pierce the darkness, eager to obey and confirm the Freiherr’s assumptions. The wind howls around them, tugging at their coats, sometimes billowing them over their heads; the trees sigh and creak. Amid all the danger, it’s a wondrous bliss to stand there, united against all waves on this side and beyond the grave.

After a long, silent wait, Reichenbach says with a hint of disappointment, “Well, it’s probably not dark enough for it.”

But just then, Friederike feels as if her eyes can catch a glimmer of light. She doesn’t know if it’s near or far, but it grows clearer. “There’s something there,” she whispers anxiously, “it’s like individual threads rising from the ground—greenish threads, swaying back and forth, and then… yes, higher up, they merge into a greenish haze.”

Yes, that’s exactly what Reichenbach expected. Through the loose earth, Od light emerges in individual threads, converging into a luminous cloud.

“Wait!” he says, pulling out his pocket lantern and letting Friederike guide him.

“There it is!”

After a fierce struggle against the wind, he lights it, illuminating the mound. A plaque on the iron cross bears a name and a death date. The woman died less than four weeks ago.

Reichenbach extinguishes the lantern again, and they must stand in the dark for a full hour before the external light stimulus fades from Friederike’s eyes. But then the entire cemetery comes alive with the ghostly light of the dead. It rises from the earth, emerges from the mounds, floats in greenish or yellowish clouds over the graves, pressed down by the wind then torn upward. The shapes of the graves stand out clearly; some show two brighter spots, likely corresponding to the head and chest of the deceased. It undulates with torches; whitish smoke swirls, pools of Od light are scattered, wisps of light are whipped away and swallowed by the night. Many graves remain dark; some barely shimmer, while others ceaselessly exude a network of light, its threads intertwining—the light the dead still send to the upper world as their last share of life.

Leave a comment