OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

“Yes… and this time for good, Ottane!” Max Heiland made a small hand motion over his eyes, as if wiping away a veil—a thin, annoying wisp like a spiderweb.

Perhaps it was this small gesture that left Ottane utterly defenseless. Yes, it was still the same graceful, skilled, beautiful hand that had once unraveled her with tender caresses—a hand whose imagined touch in sleepless nights still set her body ablaze. And now that life-giving hand passed over Max Heiland’s eyes, brushing away an invisible spiderweb. Ottane stood before Max Heiland, trembling to the roots of her being, to the last drop of her blood.

“When do you plan to travel?” she asked finally.

“I think in two to three weeks I’ll be ready; I still have some things to arrange. I’d like to go to Italy—Venice, Florence, Rome… one wants to see something yet…”

“Yes… certainly!” said Ottane, and her heart tore at the dreadful conclusion she drew from Max Heiland’s final sentence.

“May I come to bid you farewell before I leave?” Max Heiland hesitated.

“Come!” said Ottane firmly, extending her hand.

“You must have patience,” Hofrat Reißnagel consoled Freiherr von Reichenbach. “In Austria, everything always takes three times as long as elsewhere. But suddenly the railway construction will take off here too, and then you’ll have the advantage. The capital you’re now pouring into the tracks will yield a hundred percent return.”

Hofrat Reißnagel spoke easily, but the capital in question wasn’t something to be brushed aside. It was high time to see some of the promised returns. Meanwhile, Reichenbach had to pile mortgage upon mortgage, and it still wasn’t enough; overdue bills occasionally caused trouble.

Ruf had gone to the city to collect money that had to be sent out today. He was expected back by noon, but it turned to afternoon and evening, and Ruf still hadn’t appeared at Kobenzl. Ruf had reformed his lifestyle, performing his duties conscientiously; the reinstated accountant Dreikurs kept a close watch on him. But today, Dreikurs had traveled to Krems for the baptism of his third grandchild, so Ruf had to be sent to the bank instead. Could it be that he had succumbed to a relapse into his former recklessness on the way? The Freiherr grew uneasy; sitting at a heuriger with a bag of money—God knows in whose company—was risky. Besides, there were rumors that a vagrant had been spotted lurking in the woods around Kobenzl, frightening the market women.

Early the next morning, the Freiherr went to the dairy himself to inquire at Ruf’s lodging. “The father hasn’t come home,” said Friederike, looking at the Freiherr as if the Last Judgment stood before the door.

Reichenbach rushed to the city and to the bank. Yes, the steward Ruf had been there yesterday morning and withdrawn the money—fifteen thousand gulden. They took the liberty of informing the Freiherr that this exceeded his account, and they requested new collateral. The Freiherr’s knees began to wobble; a sudden roar filled his ears, as if he stood amid his Ternitz ironworks.

“Fifteen thousand gulden?” he asked.

Yes, fifteen thousand, confirmed by the Freiherr’s authorization. They recalled it clearly—Ruf had been in a hurry and left with a woman who had come with him and waited.

“Very well,” said the Freiherr, “I will arrange for the collateral.”

“Have you seen Baron Reichenbach?” the procurator asked the cashier after the Freiherr had left. “He doesn’t look well at all. I believe this scandal has affected him more than he lets on. Have you read that Reckoning by this Herr Schuh against Reichenbach? What do you think of it? And now Reichenbach and Schuh are in a lawsuit with each other. Let’s hope our settlement with the Baron doesn’t turn into a lawsuit too!”

The procurator enjoyed such jests, but the Freiherr felt no amusement as he drove home from the police. They had asked if he had any idea where the steward might have gone with the embezzled money. The Freiherr had no clue; he only suspected Ruf might have a woman with him. Perhaps that offered a lead. They promised to do their utmost but didn’t hide that it would be challenging with the twenty-four-hour head start the swindler had.

When the Freiherr re-entered Ruf’s lodging, Friederike immediately knew what had happened. “Yes,” said Reichenbach, “he took a draft for fifteen thousand gulden; he must have added a one and fled with fifteen thousand.”

Friederike backed against the wall where her father’s prized pipe collection hung, pressing her clenched fists to her mouth. She stifled a scream, forcing it back into her chest, but the innate cry raged like a wild beast within her.

“He’s being sought by the police,” the Freiherr added.

“And I… and I,” Friederike finally managed to say, “it was I who begged you to overlook it for him.”

“I shouldn’t have put him to the test,” Reichenbach remarked.

He genuinely reproaches himself. Naturally, he can’t spare Friederike’s feelings; he must state the truth, but seeing the girl in her utter misery, he can’t help but take some of the blame upon himself to lessen the blow for her.

He steps to the window and gazes into the courtyard, where the maid is mucking out the pigsty. A farmhand passes with a pair of horses, and the pigeons, vying for the chickens’ feed, flutter up with clattering wings. In the bare top of the chestnut tree sits a large black raven—the bird of death, the omen bird—already surveying the yard.

He’ll likely have to sell all this soon, just as he sold his estates Nißko and Goya. Where will he find the collateral? The beams are already creaking under the mortgages.

Not a sound comes from Friederike; it’s as if she’s left the room.

But as Reichenbach turns back, he sees her collapsing against the wall.

She grasps for support, pulling down one of her father’s large meerschaum pipes, its gold-brown smoked head shattering on the floor. Reichenbach arrives just in time to catch the girl before she falls.

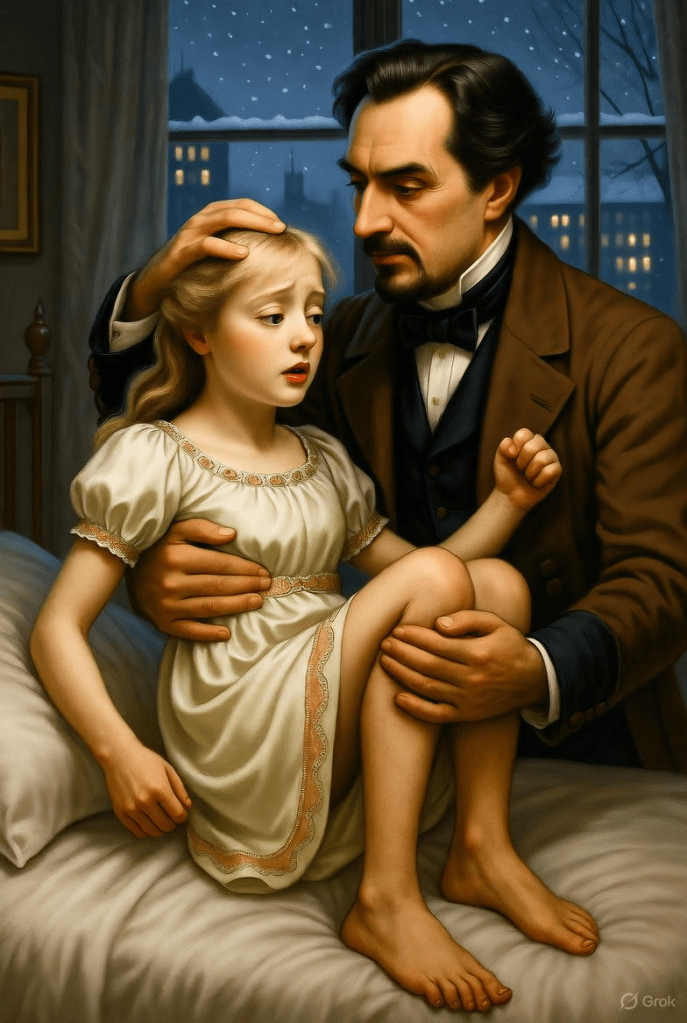

He lifts her and carries her to the bed; spasms ripple across her body, her hands clench into fists then relax, her legs stiffen, and her mouth trembles with pain. Yet amid all this, the girl’s face holds a delicate, touching beauty—touching especially for that mysteriously familiar quality Reichenbach can’t name. Reichenbach is deeply dissatisfied with himself for blurting it out so harshly; he feels as if he’s trampled young crops with waders. There lies the girl, looking at him like her executioner yet with such submission, as if he couldn’t possibly hurt her.

He places his left hand on her head and strokes her forehead with his right. “Now, now,” he says, “it’s not so bad that it can’t be made right again.”

After the third stroke across Friederike’s forehead, she closes her eyes, and her body loses all spasmodic rigidity. She seems to have fallen asleep, lying with closed eyes, breathing calmly; her misery is at least lifted for a time. And Reichenbach thinks he could now slip away.

But then Friederike says softly, yet perfectly clearly: “No, please, don’t go!” What’s this? Is Friederike not asleep? Or is she asleep and speaking from that state? And how could she know he was about to leave, how could she know before he betrayed it with a movement? Is this no ordinary sleep into which he inadvertently plunged her? Reichenbach pulls himself together—no fantastical speculations now; it’s time for precise observation. He will think of something specific; he will, for example, think that Friederike should ask for a glass of water.

At that moment, Friederike’s lips move as if sensing the discomfort of thirst, and then she says, “Please, give me a glass of water.”

By God, it’s true—the girl can pluck unspoken thoughts from Reichenbach’s mind; it’s no ordinary sleep, it’s a somnambulistic state in which she lies before him. Friederike is odically linked to him; the Od developing the processes in his brain has penetrated her and conveys to her somnambulistic consciousness the knowledge of his thoughts. It’s as he said—the Od also explains the phenomena of thought-reading.

Reichenbach reaches into his coat pocket and grasps a key. “Do you know what I’m holding?” he asks breathlessly, without pulling it out.

“You have a key in your hand,” says Friederike.

The Freiherr has never pursued these matters before; he had classified them theoretically among Od’s effects but hadn’t yet approached them with experiments. New territory opens before him—he has had a girl beside him for years who surpasses all other test subjects in sensitive powers, and precisely Friederike he never drew in or tested for her odic abilities. He hadn’t the slightest thought of it, and it’s as if she had hidden from him, as if she had avoided him.

Leave a comment