Chapter 12: Whispers of Division

Wayne and Char were still working on their base camp elsewhere and making good progress, their efforts filtering back through clan chatter. They invited Tobal to stop by if he was ever in the neighborhood and gave him directions, their warmth a welcome contrast. At least they were not mad at him. Tara was still looking for someone to partner up with for the winter and wasn’t doing so well with the construction of her own base camp out in the wilds, her frustration evident in her tales of uneven logs. It was pretty obvious she was looking for a man, her glances lingering on passing clansmen whenever she visited.

Tobal saw some of his other friends gathered by the kitchen and waved. “Hey, good to see you!” he called out. Only a couple waved back, while a few looked the other direction and moved away, their silence a cold shoulder. He shrugged it off, the sting lingering as he wandered toward the circle area.

Ellen approached him later, her expression stern. “Tobal, there’s a lot of talk about the newbie shortage. People are upset—Zee, Kevin, and others waited at Sanctuary after the storm, worried about you, while you trained the only one available. There could be hard feelings unless more newbies start coming.” He nodded, the weight of their resentment settling in.

Seeking clarity, Tobal requested a private word with Ellen later that day. They stepped aside near a quiet grove, the rustle of leaves overhead. “Ellen, can’t we reduce the newbie requirement from six to four? It’d ease the strain on everyone.” She shook her head, her voice firm. “The Federation would never allow it. Most trainees who complete the Sanctuary Program are recruited by them, especially those with a strong link to the Lord and Lady. Six is needed to anchor mastery deeply at the soul level, forging a soul-deep bond.” She paused, then added, “Will you join the small meditation group tomorrow morning? We’re focusing on a special realm.” He agreed, curiosity piqued despite the tension.

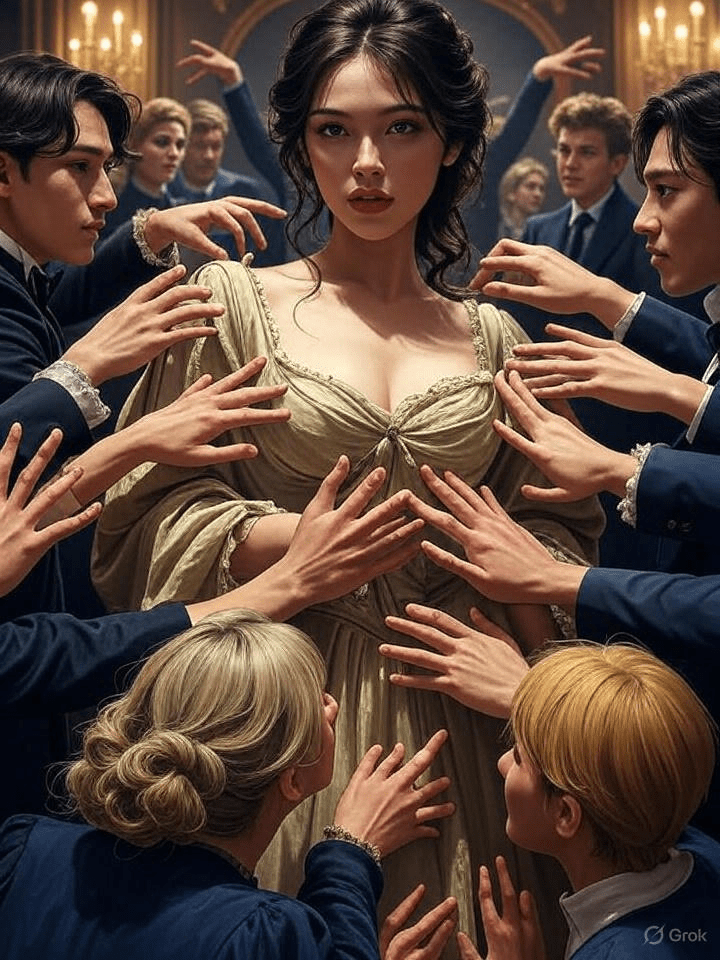

The initiation ceremony began that evening under a rare blue moon, a second full moon gracing the month—a phenomenon occurring once a year. Tobal stood in the circle, waiting for the ritual to unfold, the air thick with anticipation over Fiona’s quick prep. As the hoodwink was placed, she tensed, her hand twitching toward her knife, a reflex from her past. Rafe, newly minted as a Journeyman, stepped forward, his calm voice steadying her. “Easy now, you’re safe here.” The drums beat a deep rhythm, and Tobal felt the power grow, sensing the Lord and Lady’s presence with his inner eye. Their energy carried an angry tinge, unlike his own initiation, a discord that unsettled him. Fiona stood proudly through the jostling dancers, her tunic cut high, revealing glimpses in the firelight, and Tobal watched from the circle, his responsibility a quiet focus.

After the ceremony, as the clan mingled under the blue moon’s glow, Becca approached Tobal near the fire, her red hair catching the light. She stood silently, head bowed, tears in her eyes. “I’m sorry,” she said. “Please forgive me. I didn’t mean to hurt you.” His nerves snapped. “Get away from me! Get away from me!” he screamed. She stumbled away, crying into the night. Tobal retreated to the shadows, fighting tears, a flashback of her claws raking his face flooding his mind, bitterness choking him.

Later, Rafe found him in the shadows, asking, “What was that? Do you know her? Have you met before?” Tobal touched his scars, choking, “She did this to me.” Rafe gasped, “Oh, God!” and left, the humiliation burning as Tobal stayed there, the party’s noise a distant hum. The night wore on with raucous laughter and drumming, the clan celebrating Fiona’s initiation.

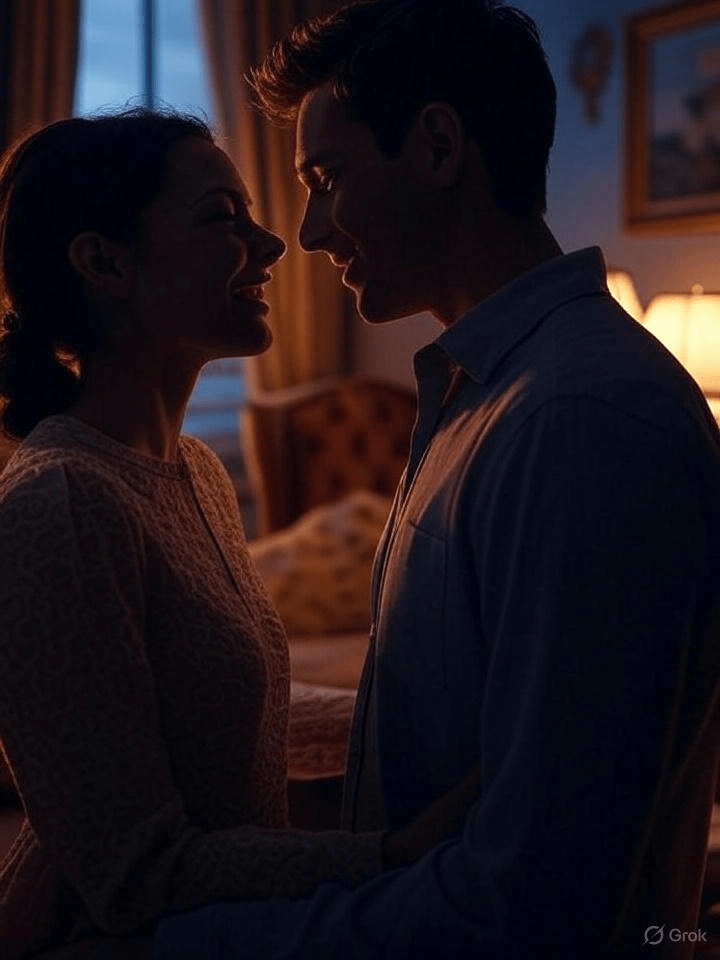

Toward evening, Fiona found Tobal in the shadows, her eyes puffed from crying over the night’s events. She held him, and he returned the embrace, her warmth easing his pain. “Thank you, Tobal,” she whispered. “This is sanctuary, the safest place I’ve known, and you’re my closest friend.” She kissed him deeply, a fierce embrace. She then invited him to travel with her to Sanctuary for some more newbies, but he demurred, needing to stay for the meditation group meeting.

The next morning, Tobal joined the small meditation group, the air thick with incense and a charged silence. Ellen led, her voice resonant. “The Lord and Lady guide us through Yggdrasil, the great tree of realms. Midgard is our earthly home, where we toil, and Vanaheim is a realm of harmony and growth, a place of spiritual freedom. Today, we’ll reach for Vanaheim.” They closed their eyes, and Tobal’s spirit surged upward, the air crackling with intensity. In Vanaheim’s golden light, the Lord and Lady appeared, their forms radiant, stirring memories deep within him—of a warm hearth, a lullaby’s echo, a father’s steady hand, a mother’s gentle touch. Instinctively, he felt a bond, a connection he couldn’t name, their presence a silent strength that enveloped him in a wave of warmth and longing. The air pulsed with their energy, a subtle yet deeply moving force, yet he knew his body remained a prisoner in the cell of flesh, a deep knowledge that stirred his soul.

A few days later at Sanctuary, Tobal met Nick, who fumbled with a heavy pack. “Need a hand?” Tobal offered. Nick grunted, “I’ll figure it out,” his stubbornness clear, setting their challenging dynamic. August brought eight newbies, a summer first, and Tobal lucked into Nick as the eighth.

They went to Tobal’s main camp, spending the first week completing winter shelters and crafting stone axes, the reversed methods from Rafe’s teachings tripping them up. Nick, strong but clumsy, excelled at chipping flint, though hunting eluded him until repetition clicked. It was a hard month, Tobal’s patience tested, but Nick was ready to solo by the time of the gathering, his progress a steady climb.

Tobal spent the evening mingling, chatting with Wayne about his jealousy and offering to mediate, then with Char about her training hopes. He spoke with Tara about Nick’s solo prep, noting her interest, and learned from Rafe about two Apprentices quitting for New Seattle. Rafe mentioned Dirk’s recovery, easing Tobal’s guilt, while Misty’s challenge loomed, the clan’s mood warming under the moonlit gathering.

The second circle convened that night, the chevron ceremony under the full moon. Tobal earned his first chevron, the stitch a badge of pride, while Fiona and Becca were recognized for their solos. As they headed for robes, Fiona caught up. “My solo was great—I found a spot east of your lake, past the stream. Started my camp—stop by!” She marked his map, ten miles in rough terrain. “Show me the way?” he asked. She smiled, “Anytime, but I’m training a newbie before winter.” They hugged, and she once more asked if he wanted to travel with them to Sanctuary, but he said he needed to stay for the meditation group meeting.

After the second circle Rafe caught up to him, his black Journeyman outfit crisp. They exchanged stories, and Tobal said, “My camp was torched—three people did it. Then Fiona and I found a village, an old camp with a mass grave. Air sleds buzzed us, no waves. It felt… haunted.” Rafe nodded, “I’ll ask around—seen others mention non-medic air sleds lately. Might be something.” He then shared clan news: fewer at circle, romantic splits, a new gathering spot rumor. Ox had complained about the knife threat, leading to first-come, first-served at Sanctuary, but Fiona’s under-28-day training raised eyebrows—her case was the exception, a concern among some. Rafe added, “Fiona can handle herself, though!”

The next morning, Tobal attended the second meditation group, the air heavy with anticipation. Ellen guided them again, her voice steady. “We return to Vanaheim, seeking its harmony to strengthen our spirits.” They closed their eyes, and a powerful surge lifted Tobal’s spirit, the air thrumming with energy. In Vanaheim’s golden expanse, the Lord and Lady appeared, their presence vast and luminous. Tobal felt a pull, his spirit soaring alongside the group in an astral projection—ethereal forms gliding over fields of light, the realm’s peace contrasting their earthly bonds. The Lord and Lady’s silent gaze seemed to guide them, a shared strength flowing through the group. Returning, Tobal’s body trembled, the experience vivid. Afterward, Ellen asked, “What did you feel?” Tobal murmured, “A freedom like we’re more than our physical bodies,” sparking a discussion on how Vanaheim’s energy could aid their training, their voices blending awe and resolve.