OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

Chapter 13

All this would certainly have moved and drawn Reichenbach in more deeply if he hadn’t been entirely absorbed by his momentous discovery. What were shootings, revolution, and constitution—here it wasn’t about things of yesterday, today, or tomorrow, but about decisive questions of humanity, beside which even Semmelweis’s new knowledge shrank to a trifle.

Reichenbach went hunting for people of the kind he called sensitive.

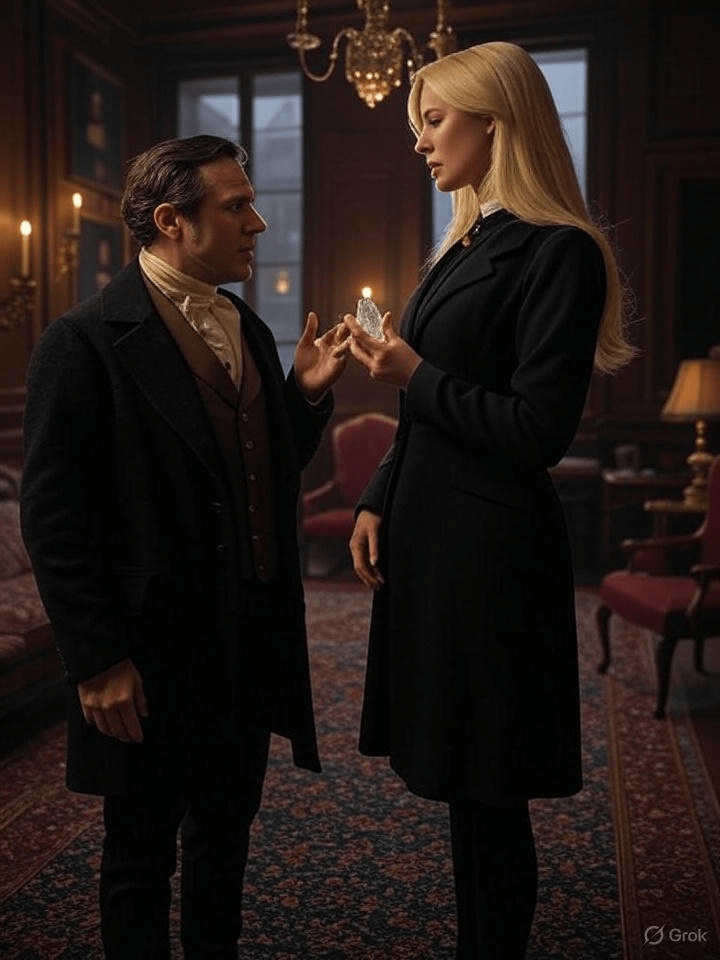

He hosted gatherings, solely to approach his subjects, drumming up his entire extensive circle of acquaintances, cornering individuals, and bombarding them with the most surprising questions. He had them place their fingertips on the room wall, gave them water to drink from two different glasses, led them before a mirror, pulled crystals from his pocket—tourmalines, feldspar, rock crystals, directed the pointed end toward one of their hands, and asked how they perceived it—coolly pleasant or lukewarmly repulsive. His system had since been expanded and significantly refined; he brought in all of physics and chemistry to relate them to the newly discovered natural force and to test the unknown against the known.

When he first found someone whose responses confirmed the experiments with Frau Hofrätin Reißnagel, he fell into an indescribable rapture. It was the wife of Police Commissioner Kowats, who stated that the pointed end of a rock crystal felt cool, while the blunt end felt lukewarm on her left hand. Yes, a clear cool breeze blew from the crystal’s tip over her hand. Reichenbach pressed his questions further into the police commissioner’s wife, and her statements aligned entirely with his preliminary assumptions.

The Freiherr breathed a sigh of relief; a weight was lifted from him—by God, the Hofrätin was not an isolated case; it was proven that other people felt the same or at least similar sensations. Now no one could reproach him for lacking the necessary scientific caution. If something still wasn’t quite right, it wasn’t due to the matter itself but to his still imperfect understanding.

Still, the police commissioner’s wife was a tall, lanky blonde with languishing eyes, and it was said she secretly wrote poetry, which always carried a slight suspicion of clouded intellect. Perhaps a malicious person could have argued that neither the Hofrätin nor the would-be poetess were entirely reliable as test subjects. It was necessary to continue searching, to expand the circle of sensitives.

And it was as if a spell had been broken; fortune favored Reichenbach. The wife of schoolteacher Pfeinreich on Reichenbach’s estate Gutenbrunn joined on a rainy day, which Reichenbach spent at the teacher’s house. Then came the wife of the smelter official Ebermann, then Anna Müller, the wife of the innkeeper on Reichenbach’s property Krapfenwaldl near Kobenzl, and then one after another.

The gift of sensitivity was tied to no class, no education level, no social stratum; it was found in all layers, from the Hofrätin to the kitchen maid. It was a universal human trait, more pronounced in some, vaguer in others, and in some seemingly overlaid by a layer of insensitivity.

So far, however, it had been exclusively women through whom Reichenbach saw his theory confirmed; he wanted to take a step further—it must be proven that this gift was not gender-specific but also present in men.

Reichenbach conducted his first experiments with Ruf. But there was nothing to be done with Ruf. Ruf was hardly ever sober; he grinned, eager to please the Freiherr, but gave the most incorrect answers imaginable, which couldn’t have been less suited to the system. He might have been useful for managing the estate, but he was utterly useless for science. Moreover, it seemed to Reichenbach that things in the estate management were no longer running smoothly, but the Freiherr had no time to deal with it now—greater matters were at stake. At any rate, Reichenbach snapped at his steward: “It’s getting to be too much, the way you carry on, Ruf. Don’t think that you may get drunk every day just because you came from Prince Salm to me. That must come to an end.”

Ruf placed his hand on his heart and protested: “But in service, Herr Baron, in service… no one can…”

“Enough,” Reichenbach waved him off, “sleep off your drunkenness now. And the womanizing must stop too, understood!” For a moment, he thought of Friederike’s pale, sad face and her sorrow, but he had no time to deal with these minor matters—though he wanted to issue a warning to Ruf anyway.

Ruf proved useless, but soon after, as if in compensation, Reichenbach encountered a clerk from the imperial and royal war accounting office, then a factory owner from Transylvania, then the Swiss ambassador, and a carpenter working in the house, and even some professors, thus growing the convincing power of his discovery to full scientific completion. Yes, men also passed his tests, though there were certain differences between their odic behavior and that of women. The circle was closed.

Initially, people had watched the Freiherr’s oddity with an almost pitying smile, but when news of what it was about spread, many came of their own accord to be tested.

“Have you been to Baron Reichenbach yet? You must go there! It’s certainly peculiar; one can’t explain everything. There’s surely something to it.”

Reichenbach’s new natural force was on the verge of becoming popular; people wanted to have been part of it, to be able to speak about it. There was certainly some force, a dynamis! What did he call it? Od? That was easy to remember: Od! The odic flame! One was charged with odic flame, positive and negative; once made aware, one could feel the Od themselves. One only needed to stretch out a hand and felt it crawling and tingling in the fingertips.

There was eager coming and going in the house on Bäckergasse all winter, and all summer on Kobenzl, and then again the following winter in Bäckergasse. Only in the October days was there a brief interruption when the streets of Vienna fought for young freedom and the city was besieged.

Reichenbach was still on Kobenzl then. He heard the cannons and gunfire, but it didn’t disturb him further; now, with no visitors able to come, he finally had the leisure to organize the wealth of material he had amassed and begin his book on the sensitive human.

He would have loved to discuss everything with Schuh. He knew Schuh would have resisted to the utmost, but that very resistance would have spurred Reichenbach more than he could say to convince this skeptic. It would have been a success that would have satisfied Reichenbach.

Schuh remained stubborn and didn’t come. But Doctor Eisenstein came and fawned around the Freiherr and Hermine, gladly spreading himself in the field Schuh had vacated. Oh, he could also play a little piano—not as virtuosically as Herr Schuh, of course, since one had a profession—but it sufficed for household use, perhaps. It would have been an honor for him to play music with Hermine or accompany her singing. Hermine regretted not having time now; she had to set music aside for a while, not wanting to be distracted while working on her treatise on the thylli.

She was still working on her treatise on the thylli; it was a difficult task with no end in sight. The father didn’t push her or stop her from singing; he was consumed by his Od, allowing Hermine to work undisturbed and with care for once.

She persisted, and it seemed endless. When Ottane looked at her sister and thought of the thylli, it always reminded her of Penelope, her loom, and the suitors. Perhaps Hermine feared that Doctor Eisenstein, now acting so at home in the house, was very much to the father’s liking, and the thylli were something like Penelope’s garment.

Eisenstein was truly at home in Bäckergasse and on Kobenzl, making himself indispensable as best he could. He was always there, obliging, obsessive, like chives on every soup. He always brought something—a new piece of music, a bag of candies, or at least some news. Had they heard that Herr Schuh, who was no longer seen, had held several performances of his so-called light paintings at the Josefstädter Theater? A new gimmick, various images projected onto a screen, entertainment for the audience, but it hadn’t quite met Schuh’s expectations—the audience stayed away; he played to empty houses. And had they heard how people spoke of Hofrat Reißnagel’s official duties? He was in the administration of state properties, and his office was called the state domain squandering bureau—yes, forests were indeed being sold at giveaway prices to favored individuals, and it was said that if this continued, Herr Moritz Hirschel would soon have the entire Vienna Woods logged. And had they heard that Therese Dommeyer and the painter Max Heiland, who were known to be very close, had now completely fallen out, and it was said the reason was a beautiful Spaniard, the wife of Colonel Arroquia, who had let Heiland paint her in a, well, rather mythological style?

With such stories, Eisenstein thought to make himself agreeable, but Hermine and Ottane listened with impassive faces and hinted that the affairs of Schuh, the squandering of state properties, and Max Heiland’s adventures were of no concern to them. They guarded against showing when an arrow struck their hearts; Eisenstein was not the man to let suspicions arise in, least of all Eisenstein.

As for the Freiherr, odically speaking, Eisenstein was neither lukewarmly repulsive nor coolly pleasant to him.

He also fawned around the Freiherr, danced about, praised, and admired in the highest tones, found everything astonishing, agreed with everything—but Reichenbach didn’t know what to do with him. He couldn’t use such yes-men. He had completely forgotten that it was Eisenstein who had set him on the path to his discovery; Reichenbach was fully convinced that everything was due to his own mind and observational skill. When the Freiherr conducted his experiments with the Hofrätin, who remained the most sensitive of his sensitives, he simply brushed Eisenstein aside. Perhaps precisely because something whispered to him that Eisenstein did have some merit in the matter. Reichenbach didn’t want to hear about it—why did Eisenstein impose himself so much, what did Eisenstein really have to do with it?

What Reichenbach needed were people like Schuh. But just the people he needed didn’t come. Schuh didn’t come, and neither did someone else who was also needed.

Leave a comment