OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

Chapter 9

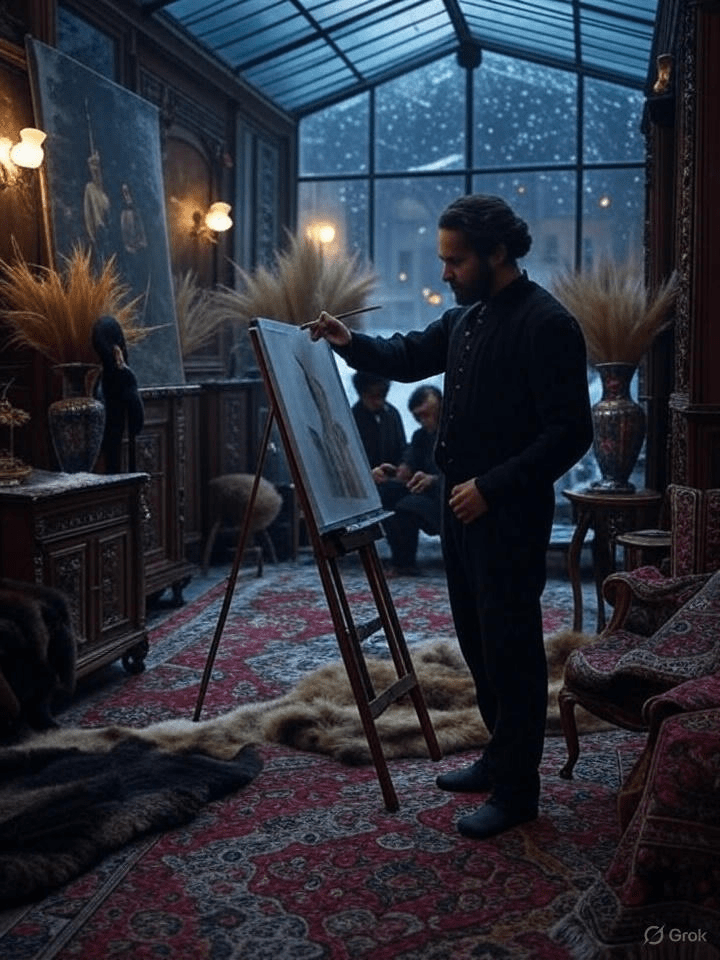

Ottane’s picture, which is to become Max Heiland’s masterpiece, still stands on the easel.

A layman might perhaps say that it is finished, but the master still finds something to improve; it is to be his masterpiece, and that must not be given up so carelessly.

“Any random lady from society can be painted down as fast as the hands can manage. There sits the model, and there is the canvas. Stroke, stroke, stroke—one only needs to paint what one sees. That’s mass-produced goods, what one gets before the brush. With you, it’s different, Ottane! You are unique in the world, Ottane!”

And: “You mustn’t grow impatient with me, Ottane! You pose the greatest challenge to my art. With you, Ottane, I must also paint what one cannot see—the soul.”

When Max Heiland says “Ottane,” it’s always like music; it flatters the ear like an Italian aria. And one becomes just a little dizzy in the head from it, and the heart beats a bit stronger too.

It also beats stronger when one enters Heiland’s atelier. Not only because it lies so heavenward under a glass roof in Spiegelgasse and one must climb many stairs, but perhaps also because it has, so to speak, something exciting about it. All painters like to surround themselves with beautiful, rare, and gleaming things; all would gladly elevate their outward existence into the extraordinary—if only they had the means. But few have them. Max Heiland, of course, need deny himself nothing; the women crowd to him to be painted, money plays no role—perhaps because he despises it. His atelier, therefore, is no bare hole like that of a colleague who paints animal pieces or still lifes, bought by petty bourgeois and officials, or who sits with his easel outside before the landscape.

When one enters Max Heiland’s studio, it’s as if one steps into the splendid chamber of a Venetian noble. Persian carpets and animal pelts, Italian glassware, weapons, armors, embroideries on the walls, church vestments thrown over inlaid chairs and Turkish divans, carved cabinets and chests stand about. Vases of man-height, in which dry grasses, thistles, peacock feathers, and artificial flowers are united into bouquets. East and West seem to have poured their treasures over the master; the past and the new age have heaped their precious items here. And amid all this clutter, absorbed by him, sprayed over it, is the scent of women, of many women who were here, some of whom were shameless enough to offer their naked bodies to the painter. Art, they say, art is the justification for that, but Ottane couldn’t bring herself to do it, no, she would be incapable of it.

Now no other women come here except Ottane. Max Heiland says so at least; he has had a barrier put up at the entrance, he turns everyone away to concentrate all his energy on Ottane’s picture. Only Hermine comes with her to the sessions; she doesn’t pay, she is the chaperone, as Heiland calls her; she doesn’t disturb much, for most of the time Karl Schuh comes along. Then they stand by the window or sit in a corner, behind a brocade curtain, and speak quietly with each other.

And sometimes Therese Dommeyr also sweeps in. She certainly disturbs a bit more; she laughs a lot, peeks curiously into every corner, lifts all the cloths as if she is looking for someone hidden underneath, throws herself onto a divan, and drinks a sweet liqueur that Heiland pours for her from a cut-glass carafe. But she seems to have a kind of house right here, which she exercises without hesitation; there’s nothing to be done about it, even if it’s sometimes annoying. The master himself occasionally grows impatient when she behaves so unruly and expressive, as if to suggest that the others were merely tolerated by her and as if she were the main figure. He frowns, becomes taciturn, whistles between his teeth, and deliberately overlooks her.

But she pays little heed to that, continues to laugh, and finds it immensely entertaining to watch the master paint. Her quick little eyes dart between the model and the painting, she praises both, the original and the copy, but sometimes, when Ottane unexpectedly casts a glance at her, she has the impression that a hostile malice darkens in those eyes. And if only she would at least stop her often rather embarrassing jokes. What, for example, is the meaning of her saying one day: “So, Maxi, that would have been a fine embarrassment for you if you had to give one of us a golden apple as a new Paris. I think you’d know even less than he what to do with it.” Isn’t that really malicious, to ask such questions? The master looks very annoyed and clearly doesn’t know what to say.

It’s only a stroke of luck that Karl Schuh is there; he has such a bright, cheerful voice and calls from the window: “Well, we’ve had an Athena, but a Juno is still missing us, and for that we have Venus twice!” With that, he makes his cheekiest rogue face, winks with his eye, and dangles his legs like a street urchin while sitting on the windowsill. Then everyone laughs, and the mythological embarrassment is over.

Overall, though—aside from Therese Dommeyr, as mentioned—these are the most beautiful hours Ottane has ever lived. She has nothing to do but sit quietly and chat with Max Heiland. He questions her about everything—her youth in Blansko, Reinhold, her father—and then he holds up his own grand life against her small, confined one, telling stories from Rome, Paris, Naples, Venice. He has been everywhere; he truly knows the whole world; he mentions the names of crowned heads, prominent figures, as if they were as familiar to him as the grocer downstairs in the neighboring house.

But it’s most beautiful when they are completely alone, for Karl Schuh thinks it’s by no means necessary for Hermine and he to sit up here the whole time; they could just as well go for a walk in the meantime; he finds that Hermine’s face has a pallor from staying indoors; he finds that exercise could only be beneficial for her. Even today, he persuaded her after a bit of coaxing to leave Ottane and the master with his art alone and go out with him onto the street.

It is the week before Christmas; much snow has fallen in the last few days, and narrow paths have had to be shoveled, narrow paths between towering snow walls. If one doesn’t want to walk single file, one must press close together. The clear, calm cold colors Hermine’s face red, which only now reveals how pretty she really is with her beautifully arched brows and the wonder of her eyes beneath them.

Schuh also keeps talking nonstop; he has a lot to report. He has given up Daguerreotypy now—a good business, but in the long run boring, always bringing the faces of indifferent people onto the plate; besides, there are now quite a few people in Vienna doing the same and making a living from it. Now Schuh has turned to galvanoplasty, a new process that utilizes electricity to produce small metal art objects.

At the “Hof,” the Christmas market is set up. Booths are lined up into alleys, filled with apples and nuts, toys for children—jumping jacks, dolls, nutcrackers, balls—a world of colorful things. Heavily wrapped women sit in the booths and at the stalls, warming pans between their legs, red noses frozen under watchful little eyes.

“Look at the children,” says Schuh, “isn’t that adorable?”

Children swarm around in groups, led by their mothers, crowding before the mountains of fruit and toys; but there are also many among them who are alone with their longing and their pitiful, daring Christmas hope. A tiny tot in a thin little coat stands before a mountain of apples, a mix of red, golden yellow, and wine green, his gaze unable to move away—hungry, captive looks.

Karl Schuh buys a few apples, a handful of nuts, stuffs everything into the tot’s pocket: “There you go! Run!”

The tot stares, doesn’t understand, looks at the strange man, and then suddenly sets off at a trot—the strange man might change his mind.

“Don’t you love children?” asks Schuh. “I think it would be so nice to have children of my own. As a child, things didn’t go well for me; I always wished a strange man would come and stuff apples into my pocket. I thought, perhaps the dear God might once walk the market in disguise and stop by me, giving me a jumping jack or a sheep made of red sugar.” Oh yes, Hermine probably loved children too, but in her heart something is buried, something living is entombed there; it dares not emerge, it doesn’t even venture to stir, for fear of sinking even deeper.

Otherwise, though, Schuh is very absorbed with his galvanoplasty. He begins talking about it again and again, then interrupts himself, laughing, shows Hermine a group, a whole regiment of little Krampuses with small wooden ladders and hats made of black paper, and then returns to galvanoplasty.

As they are now pressed even closer together by the crowd, he gently slips his hand into Hermine’s muff, where it’s warm and cozy, and tries to grasp her hand. But then Hermine pulls her fingers away; she makes a small turn, taking the muff with her and depriving Schuh’s hand of its shelter.

Athena! thinks Schuh, disappointed, always only Pallas Athena—cool, chaste, devoted only to science—her soul locked, surrounded by thick walls through which no heartbeat from next door can be heard.

A group of young people pushes past, students; they force their way ruthlessly through the crowd; the bustle of the Christmas market is merely an obstacle on their path—no, they aren’t here for the children’s toys; their expressions are full of bitterness, their gestures speak of rebellion.

“Reinhold!” calls Hermine.

Yes, Reinhold is among them; he heard his sister, detaches himself from the group, and approaches the two hesitantly and embarrassedly.

“What’s wrong with them?” asks Schuh, looking after the students. “What’s gotten under their skin?”

Reinhold pulls them into a narrow side alley between the booths. “We want,” he whispers, “to go to Haidvogel’s inn in Schlossergäßchen. The police are said to have disbanded the Ludlamshöhle.”

“The Ludlamshöhle,” says Schuh, “that’s that society of writers and actors… what does it have to do with politics?”

“Nothing, not the slightest bit. That’s just it. But the police found a poster saying: ‘This time Saturday is on a Sunday!’ Because this time the meeting is on Sunday instead of Saturday.”

“Oh dear, and the police can’t figure that out,” laughs Schuh. “And so it’s suspicious.”

Leave a comment