OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

“Tell me,” the sick woman’s voice complained, “what is that over there? I’ve been seeing it all this time.”

“What do you see?” asked Reichenbach.

“It’s like a large five of cards, four spots arranged in a square and a fifth in the middle, all faintly glowing. What is that?”

Reichenbach looked around; his eyes tried to pierce the darkness; he saw no glowing five of cards, nowhere in the pitch blackness even a hint.

“Where do you see the glow?” Reichenbach took a few steps at random, bumped into something, changed direction, and groped further.

“How do you feel, gracious lady?” asked Eisenstein.

“It cools me,” said the sick woman quietly, “that feels good; the Baron is coming toward my bed.”

“Do you feel that?” And Reichenbach pressed on in the direction he had taken.

“No, please,” cried the Hofrätin in distress, “stop, stay where you are. Don’t go further. Now a warm breeze comes from you. I feel sick; I believe you are ill, Baron.”

“You’re mistaken there,” laughed Reichenbach, “I’m not the slightest bit unwell.”

“How do you perceive that?” asked Eisenstein.

“I don’t know, I can’t say. But I believe the Baron is sick or will become sick.”

“I can reassure you, Frau Hofrätin, you are certainly mistaken.”

One could hear that the sick woman moved restlessly in the bed. “I want to know what this five means. It frightens me when I don’t know.”

“One must bring light…” Eisenstein considered, “the Baron and I see nothing.”

“Let light come for a moment,” the Hofrätin groaned, “I want to know.”

Eisenstein, after some searching, found the door, opened it, and called for the maid. Although the anteroom was unlit, a faint twilight already penetrated the deep darkness. And after a while, the maid came with the lamp.

The Hofrätin lay pale, with wide eyes in the bed, staring at the opposite wall. “There… over there,” she said, and a faint hand rose.

“Where did you see the five?” Reichenbach asked again, for there was nothing but a wall with a small chest of drawers, a little bookcase, and then a double door leading to the next room. “Where… there? There?”

He pointed to the chest of drawers, the bookcase, to the pictures on the wall.

“No, much larger, as big as the door and right in the middle.”

It suddenly occurred to Reichenbach that there was the double door, and it had a hinge fitting on each side and the lock and handle in the middle—together five metal spots, a large five of cards.

“Were the spots that high?” asked Reichenbach, stretching toward the top edge of the door.

“Yes… they may have been there.”

“It’s the door,” Reichenbach turned to Eisenstein, “the fittings are brass.”

They were brass, fine, but did brass glow in the darkness? What peculiar ability did this woman possess that she saw metal glowing in the blackness?

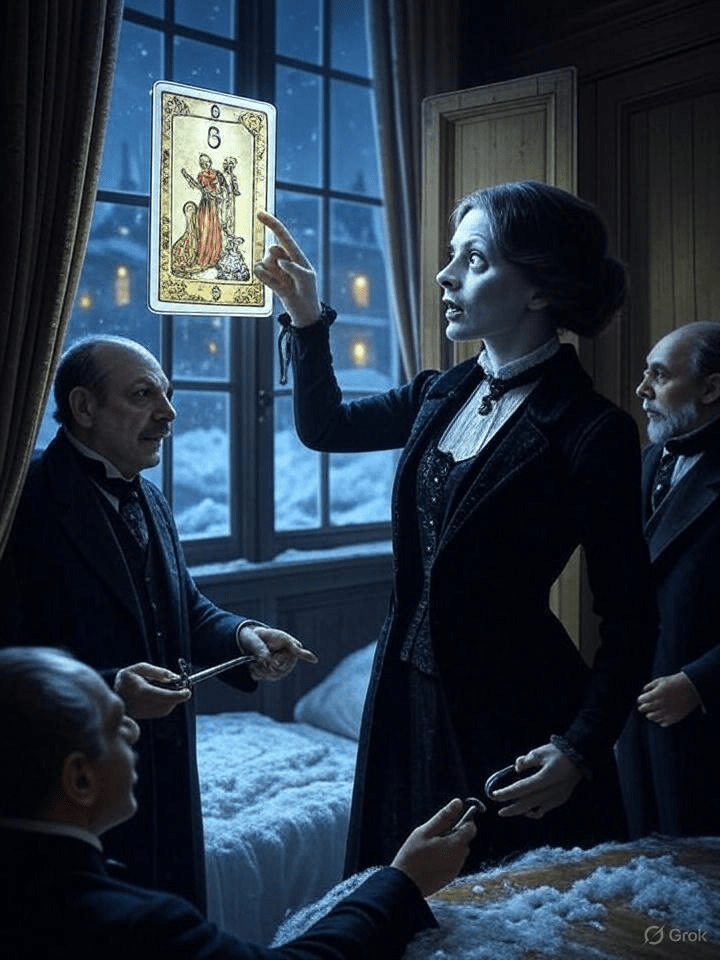

“May I,” said Eisenstein quickly, “since we now have light, I would like to show the Baron Reichenbach something, gracious lady.” He pulled something from his pocket, a piece of iron, red-painted at one end—a magnet, a common bar magnet.

The sick woman turned restlessly; she wanted to be alone again at last, but the men were seized by the ruthless zeal of science. “We’ve already tried it. Please close your eyes.” And Eisenstein comes slowly toward the bed and places the red end of the magnet rod into the Hofrätin’s left hand.

She lies with closed eyes, and her fingers clasp the iron; her features smooth out a little. “Please, how do you feel the touch?”

“Cool.”

Eisenstein takes the magnet from her hand, turns it around, and places it back into her left hand.

“How do you feel that?”

The sick woman groans; her face expresses disgust: “Warm! Repulsive!”

Eisenstein looks up at the Freiherr, who stands there shaking his head. A silent question: What do you say now? The doctor removes the magnet, gives it back to the patient, now with one end, now with the other, then two, three, four times in a row with the same end, in random alternation; whenever the Hofrätin grasps the north pole, she feels the iron cool and soothing; when she has the south pole between her fingers, it feels warm and unpleasant. She obediently keeps her eyes closed, but her answers remain certain; she doesn’t err a single time.

“Is it for this reason that you spoke of a kinship with magnetism?” Reichenbach asks finally.

“Wait?” And now Eisenstein places the magnet in the patient’s right hand.

She twists her face and breathes in gasps. “How do you perceive that?”

“Warm and repulsive.”

It is the north pole that she now holds in her right hand. With with wide-open eyes, Reichenbach stares at the slender fingers trembling around the iron. Reversed? The opposite effect from the left? Yes, by God, exactly reversed—what was soothing on the left is tormenting on the right, what was painful on the left is pleasant on the right. Eisenstein continues his experiments—ten times, twelve times—checking the phenomenon on the left hand in between; no error blurs the picture.

Then the sick woman impatiently opens her eyes, gasping: “Leave me alone at last. I can’t anymore. I cannot tolerate the light any longer.”

“Yes, yes, gracious lady,” Eisenstein soothes, “we are finished. We’ll leave now. Drink the tea I prescribed, and try to sleep. I’ll see you again tomorrow.”

Then the men stand outside the door; Eisenstein’s looks ask clearly: Well, did I exaggerate? Did I call you here for nothing? Am I now also a man or not? A man like Schuh, eh?

Reichenbach’s eyes burn inwardly. “What interpretation do you have for that… for all these phenomena?”

Eisenstein has no interpretation; he shrugs his shoulders: “The key eludes me for now. But I believe this is a matter that concerns not only the physician but also the physicist, and that’s why I asked you to come.” Eisenstein has played a trump card; he feels it, he knows that Reichenbach is gripped by the problem. Eisenstein has become an important figure. He has unleashed the passion of thought in the Freiherr, his only passion; he has shown him something new, and forced his way into the fortified house and to Hermine; oh ho, what this Schuh can do, Eisenstein can do too—make himself indispensable—and now he will surely succeed in making up for the lead that Schuh has.

The men trudge wordlessly side by side through the dark streets in slushy snow. Under a streetlamp, Reichenbach stops, seized by a thought. “Perhaps they are rays… a kind of rays emanating from things…”

He breaks off, overwhelmed by his thoughts, and Eisenstein eagerly confirms: “It could also be, in a way, a kind of rays…”

He feels with satisfaction how furiously his companion’s mind is working. In this head, it’s now a wild tumult. It’s a volcano, a sea of flames, a tumbling chaos, a roaring, a battling, a hissing of blazing thoughts; the skull walls stand under a pressure as if they must burst; the Blansko furnace, all the blast furnaces of the world, are mere panting kettles compared to it; their glow is a pitiful little fire.

Leave a comment