OD by Karl Hans Strobl and translated by Joe E Bandel

Chapter 6

The lord of Reisenberg Castle had been ennobled.

His king, the King of Württemberg, had lifted him from plain citizenry to the rank of baron. His youthful attempt to flee to Tahiti, for which he’d been imprisoned at Hohenasperg, was forgiven and forgotten. He’d been awarded the Royal Württemberg Crown Order, named an honorary citizen of Stuttgart, and now, back home, his contributions to science, especially its practical applications, were deemed so great that he could rightly be made Baron von Reichenbach.

The newly minted baron occasionally said it meant nothing to him, just something for others, but perhaps it was why he hosted this grand gathering today. This wasn’t openly declared or even hinted at, yet the guests likely thought as much when they arrived, one by one, and saw the new baronial crest carved in stone above the castle entrance.

Reisenberg Castle was originally a Jesuit country house, later acquired by Count Kobenzl, whose name gradually became tied to both hill and castle among the people. Now the old count’s crest above the entrance had been chipped away and in its place, the Reichenbach crest had been set.

“Is Reichenbach a Rosicrucian?” Professor Schrötter asks, pausing with Court Councillor Reißnagel before the door.

“Why?” the Councillor’s wife wonders.

“Don’t you see the cross with roses on the crossbars in his crest?”

“Rosicrucian—what’s that?” the Councillor’s wife asks, a slender, delicate lady with translucent pale cheeks and ever-dreamy, searching eyes.

“Rosicrucians?” her husband explains leisurely. “They’re an order, a society. They’re said to possess remarkable secrets.”

“If Reichenbach has a secret,” Professor Schrötter smiles, “it’s how to make money.”

Reißnagel chuckles. “Think so, my dear friend? It’s not that simple with the earning. He earns plenty, sure, but he’s got passions that devour money. And is the Ternitz ironworks really so profitable? You know, Reichenbach does me the honor of asking my advice now and then—on business matters, of course, not science…” He chuckles again. The Councillor’s wife hasn’t taken her eyes off the crest. “And the star in the bottom right, with arrows shooting out?”

“Those must be the meteorites, the shooting stars,” Professor Schrötter says after some thought, “that Reichenbach deals with.”

“Are the Hungarian ones included too?” Reißnagel chuckles. The councillor chuckles, and then the two men laugh in shared malicious glee.

“How’s it really going with that?” the councillor asks then, as they finally enter the garden hall and hand their coats to the servants. “What does science say about it?”

“Well, the matter has turned into a thorough embarrassment. Reichenbach has misfired once. The so-called meteorite fall in Hungary has become a fiasco for him. He calculated three hundred fifty thousand million little stones and claimed that our mountains, in part, so to speak, fell from the sky. To the Neptunian and Plutonian mountain formations, he added the Jovian ones, as he calls them. And it turned out that his Hungarian meteorites are ordinary bean ores, which have nothing to do with the sky and occur in masses on Earth. But against the opinion of the Court Mineral Cabinet, he sticks to his view. He has a thick skull.”

“Yes, he does,” the councillor confirms. “He’s a strange man altogether. A clear head, that you have to admit, but sometimes his imagination plays a trick on him. Imagination is something for poets and such folk, but not for officials, and certainly not for scholars.” And then, with a meaningful glance at his wife, he adds: “Too much imagination and enthusiasm is not for us ordinary mortals anyway.” Yes, imagination certainly holds no power over Councillor Reißnagel; his head looks like a well-ordered registry, everything filed by shelf numbers in compartments, and his rounded little belly guarantees the thoroughly earthly direction of his life philosophy.

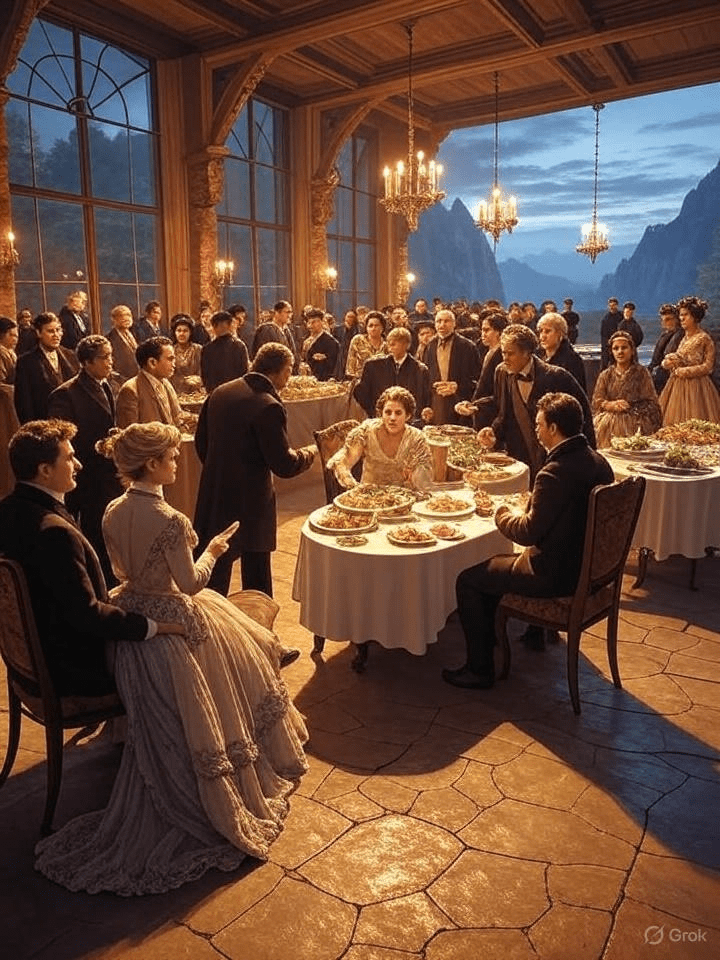

“There are so many people here,” the Councillor’s wife says anxiously. “I should’ve stayed home.” She doesn’t handle such crowds of bodies well; a disagreeable feeling rises from the haze, a mix of human breath and various odors making her restless. She can’t quite express it, but it’s anything but comfortable.

Then the rising waves of social bustle separate them. There are indeed many people in the cheerful garden hall and adjoining rooms, and Schrötter spots Reichenbach’s famous guest, Professor Liebig—he must go greet him.

To Councillor Reißnagel and his wife joins their house doctor, the young Dr. Eisenstein. He kisses the gracious lady’s hand and inquires about her health. “That’s another of Reichenbach’s passions,” the councillor says. “Inviting so many people. He thinks he has to emulate Baron Jacquin, who for thirty or forty years gathered everyone in Vienna with name or reputation. But the heathen money that costs!” With that, he takes a plate from the servant appearing before him, scoops goose liver pâté from the silver dish, and secures a glass of wine on the nearby console table. “Who’s that young man over there talking to Ottane?”

Dr. Eisenstein can provide the answer. The young man with the laughing face, the lion’s mane, and the audacious tie is, of course, a painter, the painter Max Heiland, of whom so much is said nowadays, a genius, everyone wants to have themselves painted by him, a rat catcher after whom the women run, it is said that the noblest ladies are happy to be allowed to pose for him.

For geniuses, Councillor Reißnagel has only a contemptuous growl. “They may make money, but it’s all just hocus-pocus; geniuses are only a nuisance for a decent official, an unreliable element that one can’t trust. Genius and revolution, that somehow go together.” But then his small eyes sparkle with a cold, amused light: “Aha, the host! And of course with Therese Dommayer!” He wipes his mouth, swallows the Nussberger—by the way, a splendid Nussberger—and steers eagerly toward Reichenbach and the actress.

“You haven’t given me an answer yet, gracious lady!” says Dr. Eisenstein, leading the councillor’s wife apparently casually from the garden hall onto the terrace.

Beneath the terrace, the forest mountains slope in wonderful lines down to the plain, and below lies the city with its thousands of lights in the soft darkness of the summer evening. City and river and mountains, peacefully merging, an intimate clinging together of human existence and landscape. But the young doctor isn’t interested in the landscape; he has spotted Hermine’s light blue dress outside. Was it an unfavorable coincidence or deliberate evasion that Hermine has always slipped away from his approach until now?

“I had another attack yesterday,” the councillor’s wife complains. “I almost sent for you. It was the same as always—first raging headaches, everything becomes so loud and glaring and stupefying, smells, lights, pressing in on me from all sides, hostile and threatening, then a twilight where I lose consciousness. When I came to, I was sitting on the bench in the garden. I don’t know how I got there.”

“We should try the magnetic cure after all,” the doctor says distractedly, searching with his eyes for the light blue dress he had just seen over there next to the large iron dog from the Blansko foundry.

“Oh, my husband won’t hear of it,” sighs Frau Pauline. “He thinks nothing of magnetic cures and says my whole illness is nothing but imagination.”

Meanwhile, Reichenbach has led the plump, always cheerful Therese Dommayer to the buffet and piled a mountain of sweets on her plate. Although Therese Dommayer is a great tragedienne, the greatest since time immemorial, in everyday life she has a great fondness for sweets. She saves the grand tones for the stage; her daily life is closer to a bright laugh, a silvery chime—it would be nice if this bell-like laughter could be heard more often, as much as possible.

“It’s quite nice in your city house too, dear Baron,” she says, “but out here, you first realize what a poor dog one is if you’re always stuck in the city. How divine nature is! We theater folk—good heavens, sometimes one wishes the devil would take the whole thing. She blinked slyly up at Reichenbach and then made a wistfully swelling face. “Oh yes, you rich folks have it good.”

A scent rose from her bare shoulders, Reichenbach bent slightly embarrassed over her: “Aren’t you richer than anyone else? Rich in your art! Rich in the admiration of your contemporaries!”

She swatted at Reichenbach with her hand and replied, chewing with full cheeks: “Contemporaries, you’re right, dear Baron, contemporaries! That’s just it. How long does the whole glory last? A few years. Then it’s over, especially for a woman. And then it goes: the mime’s posterity weaves no wreaths. Sometimes one has a longing: to be away from the world-famous stages, married, have a good husband, have children.” She tilted her head in an inimitable, flowing melancholy.

Councillor Reißnagel arrived at that moment very uninvited, no, he was not welcome at all. He wore his oiliest smile on his face, and his belly broadly pushed the air before him. He had to express his most submissive congratulations orally to the host for his elevation to baronial rank and for this illustrious company today, which in no way fell short of that of the late Baron Jacquin, indeed, on the contrary, through the presence of an artist like the divine Dommayer, gave a consecration often missed at Jacquin’s.

Therese nodded and calmly shoved a piece of cake into her mouth.

One could not say otherwise, the councillor continued, than that a lucky star hovered over this house, a downright Napoleonic lucky star. And if now, moreover, this process—this somewhat protracted and certainly costly process with the Salm heirs—should also come to a satisfactory conclusion…

“You know, of course,” Reichenbach interrupted, “that I won the first lawsuit…”

Leave a comment