The old count spoke without undue solemnity, yet Reichenbach sensed something weighty behind it, an inner shift toward something new.

“And what’ll happen here without you?” Reichenbach asked.

“It’s a blessing I have you, Reichenbach,” the old count replied, a wistful smile in his voice. “You don’t need me. It’s as good as if I were here. No task is too much.” Perhaps he truly smiled now, but it wasn’t visible.

“And tomorrow I’ll come by the factory again,” the old count added, then left.

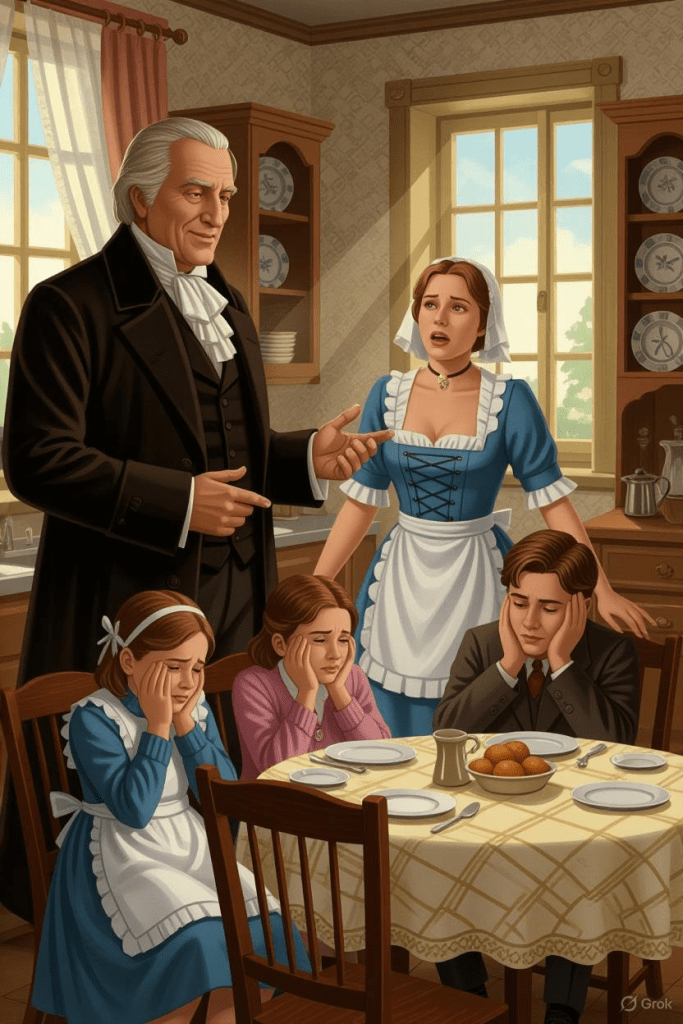

Frau Paleczek appeared with a light and set the table, but as she brought the plates, she suddenly wailed and ran out. After a while, Susi brought the supper instead.

“Where’s Paleczek?” Reichenbach asked.

“She’s sitting in the kitchen crying,” Susi said, but then her composure broke too. She swallowed hard, abruptly sobbing, pulled her apron over her face, and ran out.

After poking at his food, Reichenbach rose and went to the children’s room. It had been fumigated with sulfur and juniper and sprayed with vinegar, still smelling sharp. The children lay in freshly made beds but weren’t asleep yet.

“Have you done your assignments for tomorrow?” Reichenbach asked, standing by Reinhold’s bed.

“Herr Futterknecht said,” Reinhold admitted hesitantly, “we don’t need to do assignments for tomorrow.”

“So!” Reichenbach said, nothing more. Then: “Good night! Sleep now.” He shook Reinhold’s hand, stroked Hermine’s forehead, and bent to kiss Ottane’s cheek.

The child flung her arms up, wrapped them around his neck, and pulled him close. “Papa,” she whispered, “I’ll always be good and love you so much.”

The painfully sweet tenderness of such clinging melted the stiffness in his limbs, and Reichenbach held Ottane close.

“I promised Mutti,” the child whispered, “and she’ll always come to me and tell me what the sky-sheep sing.”

“When did you promise Mutti?” Reichenbach asked, just as softly.

“Tonight—when she was with me.”

Tonight? Tonight? What could that mean, tonight? A sudden stab of dread seared his heart. Troubled, shaken to his core, Reichenbach tucked the blanket over Ottane and went to the next room, where the drawings for the new furnace still lay on the desk.

The furnace was built to Reichenbach’s plans and exceeded all expectations. It roared, spat, and glowed, producing nearly as much charcoal as the wood fed into it, and most importantly, showed no tendency for unexpected mischief.

Once it was running smoothly, Reichenbach decided it was time to restart the abandoned Doubrowitzer hammer mill. So he put it back into operation. Then he thought it was time to build a drilling rig. He built one, installing a drilling machine—naturally, the largest in Austria,and could bore cylinders over twelve feet in diameter.

Then Reichenbach turned to agriculture, starting, as agreed with the old count, to grow sugar beets, which naturally required a sugar factory. Since farming was foreign to him, with no innate knowledge of it, nothing became more important than beets and sugar. Some things succeeded, others failed, and years passed. Looking back on New Year’s Eve, it felt like each year had only begun the day before yesterday.

Meanwhile, the old count traveled the world, writing long letters to Reichenbach about his findings.

The old count wrote that he and Lord Rumford conducted experiments on gas expansion, especially gunpowder, nearly blowing themselves up once.

He wrote that he’d heard of Jenner’s vaccination discovery, calling it a magnificent invention, and was now vaccinating himself. He sent vaccine and needles to Reichenbach for free distribution, later adding a self-written treatise on cowpox.

Reichenbach replied that it was indeed a great invention, but the people wanted no part of it. Meanwhile, the workshop was now producing hydraulic presses, water-lifting, and conveyor machines.

The old count wrote that he was now studying the Loserdorre cattle breed disease, to be fought with iron-containing hydrochloric acid, and he sent a self-written pamphlet on it. He was also on the trail of a remedy for rabies, likely in a cyanide compound. But against cholera, no cure could be found.

Reichenbach replied that the Brno censor was a fool for banning the old count’s pamphlet. As for rabies, he begged him, for God’s sake, to be careful with sick animals. Meanwhile, he was shipping barrel hoops to Singapore, cookware to Haiti, iron stoves to Turkey, and creosote to America and Egypt. He said nothing about cholera or its treatment.

Sometimes the old count came home. His eyes had a restless glint; he laughed loudly, sat in Reichenbach’s sofa corner, smoked like a chimney, and drank heavy wine. He looked over the books, made a few tweaks to the machines, then vanished again for days. During one such visit, Forester Ruf came and said, “Can you believe, Herr Director, the old count stopped by my place today?”

“So what?” Reichenbach asked. Why shouldn’t the old count visit Ruf? He roamed the valley, dropping in on folks, asking how they were, urging them and their children to get vaccinated against smallpox. Sometimes he liked to wander the woods in shabby, tattered clothes, like a traveling journeyman, chatting with old peasant women to beg from those who didn’t know him, only to richly reward them afterward if they gave him something. Why shouldn’t he have visited Forester Ruf?

“Well, but,” Ruf said hesitantly, “you won’t believe it. He sent Schnuparek’s widow, who’s watching the child, away, and when I came in, he was crawling under the table with the girl on all fours, barking like a dog, fooling around. He brought her a big new doll, too, and when he left, I saw money tucked in the mirror frame.”

“Why shouldn’t he give you money, Ruf?” Reichenbach said. “He probably remembered being at your girl’s christening and how different things were then.”

“But I don’t know if I can keep it,” Ruf stammered, flushed with embarrassment. “It’s a whole hundred gulden. The old count must’ve made a mistake.”

“Keep it!” Reichenbach urged. Yes, great lords sometimes had such generous whims, and perhaps the old count, with his incognito wandering and gift-giving, took after a caliph who’d done similar things. But Ruf shouldn’t thank him—the old count didn’t like being reminded of his kindnesses.

The old count never stayed home long. He’d look around briefly, bring gifts for Reichenbach’s children, praise their growth, looks, and progress, discuss business and new scientific plans with Reichenbach. But Friederike Luise was never mentioned.

Then the old count went on his way again.

He wrote: He had been admitted to the Société Harmonique in Strasbourg, where new and remarkable insights into human nature were to be gained. He was increasingly convinced that hidden forces lay in the human soul—a mysterious agent, a magnetic fluid, stretching into the incomprehensible. Mesmerism was merely a casual name for it. The laws of this natural force were still little explored, and he urged Reichenbach to study it, believing his skill and persistence could greatly advance science.

Reichenbach, grappling with sugar beets and tenants, thought something irreverent. Mesmerism, he felt, was for people with too much time, and it could slide down his back. A few months later, a letter arrived: the old count had become politically suspect in Strasbourg, likely because the French government had once seized his ancestral castle in the Ardennes. Facing arrest, he chose to slip away, continuing his studies in Vienna.

Then no further news came until a thick letter arrived, addressed in a stranger’s hand with black seals. It stated that the old count Hugo zu Salm-Reifferscheidt had unexpectedly died in Vienna of a heart ailment, leaving his heirs, his father the old prince, the widow, and his son, the young count, instructed before his death to renew the general power of attorney for Herr Karl Reichenbach. The enclosed power of attorney was signed in accordance with the deceased’s wishes.

This was written not by the old prince, the widow, or the young count, but by the old princely lawyer, Dr. Gradwohl.

In the midst of a heated argument with the chief accountant over booking certain items, the door opens, and old Johann enters.

He had knocked, of course, but with the shouting as the general director defended his view, no one heard it. Old Johann hasn’t grown younger since that glorious night of the meteor fall—a parchment-stretched skeleton, cheekbones nearly piercing his skin, nose crooked over a sunken mouth, but his eyes hold a strange brightness, as if seeing things clearer than younger eyes, perhaps through them. He had accompanied the late old count on his travels, not always a restful job, judging by what Johann occasionally lets slip. At any rate, he returned to the Rajzter castle quite aged and worn, and for a while, he was allowed to rest and do nothing. But then they pulled him out again, and the young count said Johann was far from too old to do nothing but smoke his pipe and whistle to his starling. The young count, barely made prince after his grandfather’s death, brought a sharper edge to everything, tightening all that was loose.

And the young prince thought old Johann far from frail enough to eat his bread for free, still capable of sitting on the coachbox, so long as it wasn’t the wild Lipizzaners hitched up. He could still save them a second coachman.

Now old Johann announces that the carriage waits outside and that His Princely Grace requests General Director Reichenbach to Rajtzer Castle. He says “requests,” though His Princely Grace simply said: Reichenbach should come.

Leave a comment