Homo Sapiens by Stanislaw Przybyszewski and translated by Joe E Bandel

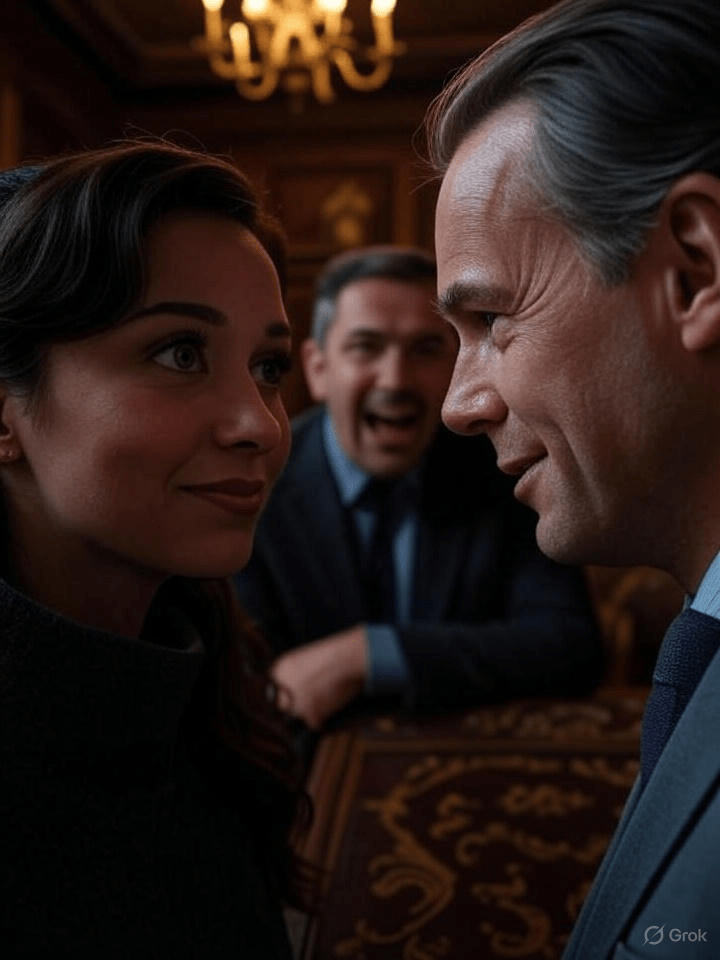

Falk noticed a shy smile on her face, as if a faint sense of shame slid across it.

“You mustn’t bore Mr. Falk with that.”

A subtle streak of displeasure flashed across Mikita’s face.

She discreetly stroked his hand; Mikita’s face brightened. She knows how to handle him, Falk thought.

The room was bathed in a strange, vermilion glow. Something like a thick red, as if fine layers of red were stacked atop one another, letting the light refract through them.

Was it the light?

No, it was around the corners of her mouth—no! Fine streaks around her eyes… It vanished again, settling into a delicate hollow in her cheek muscles… no, it was intangible.

“You’re so quiet, Erik, what’s wrong?” “God, you’re beautiful!”

Falk said it deliberately with such a nuance of spontaneity that even Mikita was fooled.

“You see, Isa, the man’s honest, isn’t he?”

Strange person! That face… Isa had to keep looking at him.

“What did you do all winter?” Falk pulled himself together.

“Hung out with Iltis.” “Who’s Iltis?”

“That’s a nickname for a big guy,” Mikita explained. Isa laughed. It was an odd nickname.

“Look, Fräulein, Iltis is personally a very likable fellow, a good man, and he gets along with the young ones. Sometimes they get too wild for him, then he slips away quietly…”

“What is he?”

“He’s a sculptor. But that’s terribly secondary for him.

Well, he only interests us as a person. And as a person, he’s obsessed with the fixed idea that someone must shoot themselves on his personal suggestion. Hypnosis is his hobbyhorse. So it happened that we drank through an entire night. The esteemed public, who take us for priests of art…”

“Priests of art! Magnificent… Temple of the Muses and Clio… Ha, ha, ha.” Mikita was immensely amused.

“Yes, the public can’t imagine how often that happens with the priests of art. After such a night, the priests crave fresh air. The lesser priests dropped off along the way. Only the great Hierophant…”

“Hierophant! Iltis a Hierophant!” Mikita shook with laughter.

“So, the Hierophant and I go together. Suddenly, Iltis stops. A man is standing by the wall, ‘staring upward,’ as Schubert puts it.

‘Man!’ Iltis says with an incredible tremor in his voice. But the man doesn’t move.

Iltis practically sparks with his eyes.

‘Watch this! The man’s hypnotized,’ he whispers mysteriously to me.

‘Man!’ His voice turns menacing, taking on the tone of a hoarse trumpet that shook Jericho’s walls… ‘Here’s six marks, buy a revolver, and shoot yourself.’

The man holds out his hand.

‘A perfect hypnosis,’ Iltis murmurs to me. With an unbelievably grand gesture, he places six marks in the man’s open hand.

In that instant, the man does a leap:

‘Now I don’t have to shoot myself. Hurrah for life!’ ‘Cowardly scoundrel!’ Iltis roars after him.

Mikita and Fräulein Isa laughed heartily. Falk listened. There was a softness in that laugh—a… what did it remind him of?

“Look, if I were a minister of culture, I’d have that cowardly scoundrel appointed as a well-paid professor of psychology.”

“Do all Russians mock so beautifully?” She looked at him with large, warm eyes.

“No, Fräulein, I’m not Russian. I was only born near the Russian border. But through close contact with the Slavs, Catholic upbringing, and such fine things, you might pick up something in your character that Germans don’t usually have. Then—well, you know, you get such interesting impressions there…”

Falk began to speak of his birthplace with a warmth that stood in strange contrast to the faintly mocking tone in his voice.

“Splendid people! Out of a hundred, barely two can read, because they’re Poles and forced in school to listen to the sweet melody of a foreign language.

Yes, they absolutely want to raise Polish children into respectable German citizens, and everything respectable, as we know, must use the German language. They beat the delightful German language into the children with true Prussian vigor, and the progress is quite striking.

The children even greet with a phrase that’s supposed to be ‘Praise be to Jesus Christ.’ But the nimble Polish tongue refuses to utter such barbaric sound combinations as ‘Gelobt,’ so the greeting becomes ‘Gallop Jesus Christ, Gallop!’ Why dear Jesus Christ should gallop, the children can’t fathom, but with a German Christ, anything’s possible. The Polish one is quite different, and the Polish God, of course, only understands Polish, just as it’s well known that paradise is to be found in Poland.”

There was something in his speech that captivated her so strangely. He could say something utterly trivial, yet he said it with a nuance, an inflection… Mikita was talking too loudly.

“You know, Erik, when we were still in the gymnasium… one teacher looked remarkably like Iltis…”

Falk half-listened. While Mikita spoke, he glanced at her from time to time. Each time, their eyes met, and both smiled.

This feeling was entirely new to him. It was as if something within him tensed, gathered—a warmth, an energy… it surged and poured into his mind.

He had truly wanted to make himself interesting. Yes, truly. There was something in him that bore a desperate resemblance to intentions, yes, intentions to captivate this woman—to entertain her…

Who was this woman?

He looked again. She didn’t seem to be listening to Mikita; around her eyes, that strange glow.

How all the lines flowed into one another behind the veil.

He almost felt the urge to peel something away from her face, her eyes.

Mikita suddenly jolted mid-story. He glanced at her briefly. Her eyes were fixed on Falk. Curiosity?… Perhaps?… Maybe not…

Falk noticed Mikita’s unease and suddenly laughed:

“Yes, it was odd. That old Fränkel—truly Iltis’s double. Remember, Mikita—that Sunday. We were sleeping; I was dreaming of the chemist, Grieser, who seemed like a towering genius to me back then. He fooled us both.

Suddenly, I wake up. Someone’s knocking at the door: ‘Open up!’

In my groggy state, I think of Grieser. But it’s not Grieser’s voice.

‘Who are you?’ ‘Fränkel.’

I ignore everything, still thinking of Grieser. ‘But you’re not Grieser?’

‘I’m Fränkel. Open the door.’

‘God, stop joking. You’re not Grieser.’

I can tell it’s not Grieser’s voice, but I open the door anyway, so sleepy I can’t get my bearings.

‘You’re not Grieser?’

Suddenly, I’m awake and stumble back in shock. It was really Fränkel. Oh God! And on the table lay Strauss’s *Life of Jesus*…”

Mikita was nervous, but the memories warmed him again. It was getting rather late.

Falk felt he ought to leave, but it was impossible, physically impossible, to tear himself away from her.

“Look, Mikita, why don’t we go to the restaurant ‘At the Green Nightingale’? That’ll interest Fräulein Isa.”

Mikita wavered, but Isa agreed at once. “Yes, yes, I’d love to.”

They got ready. Falk went ahead.

Isa was to put out the lamp.

Isa and Mikita lingered a moment. “Isn’t he wonderful?”

“Oh, marvelous! But—I could never love him.” She kissed him fiercely.

Downstairs, all three climbed into a cab.

It was a bright March night.

They drove through the Tiergarten, not speaking a word.

The cab was very cramped. Falk sat opposite Isa.

This feeling he had never known. It was as if a ceaseless heat streamed into his eyes, as if his body were drawing in her… her warmth… As if she radiated a consuming desire that dissolved something in him—melted it.

His breath grew hot and short. What was it?

He’d probably drunk too much. But no!

Suddenly, their hands met.

Falk forgot Mikita was there. For a moment, he lost control.

He drew her hand to his lips and kissed it with a fervor, such fervor…

She let it happen.

Leave a comment